Become a Creator today!Start creating today - Share your story with the world!

Start for free

00:00:00

00:00:01

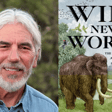

16. Sean Gerrity on the rewilding renaissance

Sean Gerrity is the co-founder and former CEO of American Prairie—a giant wildlife refuge in the making in Montana, which I hiked and kayaked this past August. Sean is the host of The Answers Are Out There podcast in which he interviews leaders who’ve taken on bold conservation projects. He’s the author of Wild on Purpose: The American Prairie Story and the Art of Thinking Bigger.

- Some of Sean’s favorite things: musician Ry Cooder, Sapiens by Yoval Noah Hariri, Travels with Charley, East of Eden, A Short Walk In the Hindu Kush by Eric Newby, Decisive by Chip and Dan Heath, and…

- Sean’s podcast interview with Violet Sage Walker — a Northern Chumash Tribal Leader — celebrating America’s Newest Large-Scale Marine Sanctuary.

- Are we in a rewilding renaissance?

- How well known is American Prairie? Is it’s under-knownness due to the noise of the modern day information flow?

- Is today the best of times (lots of exciting conservation opportunities) and the worst of times (the overwhelming negativity funneled into our brains).

- 192 out of 196 countries signing up to achieve vision of 30% of the world saved for nature by 2030.

- The big four things for helping the environment:

- Stabilize global human population

- Accelerate transition to green energy

- Rewild

- Redo how we do agriculture

- Fundraising: is it as unpleasant as it sounds?

- The art of risk-taking—analyze the risk so deeply the risk is no longer a risk?

- Do our schools need to teach “risk analysis” in their curriculums?

- MT. Gov. Greg Gianforte’s letter to the BLM opposing American Prairie’s use of bison.

- I pitch a book idea to Sean.

- American Prairie’s “Wild Sky” program, which involves paying landowners for photographic evidence of wildlife on their property, plus some wildlife friendly fencing.

- How there could be 30-40 more American Prairie-like projects, just across the American West.

- Chumash National Marine Sanctuary—4500 square miles of protecting marine habitat.

- Klamath River Dam Removal—over 400 miles of river protected.

- On how originality is overrated.

- Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing:

- George Catlin proposing a park way back in the 1830s.

- The Tarras Valley Nature Reserve project. Here’s Sean’s podcast interview with them.

- Will American Prairie need to evolve into more like a multi-entity committee in the future?

- I get Sean’s thoughts on de-extinction.

Transcript

Introduction to Sean Garrity and the Podcast Format

00:00:01

Speaker

Hey folks, Ken here. um My guest today is a big one. His name is Sean Garrity. You may not have heard of his name, um but I think ecological restoration is maybe the biggest, most important story happening in the world, if you really think about it. And if that's at all true, then my guest is a really big one. i think of him as a man of history. He is the ah co-founder and former CEO of American Prairie, which is a wildlife refuge in Montana, one of the boldest, biggest rewilding projects in the world. And this episode is long. It's very long. This is like a Joe Rogan-esque over two hour podcast. We did it over two interviews. um The first half surprised me. It's kind of more about um analyzing risk, pra project management, vision, you know, the things that go into a rewilding project that you wouldn't really think of. The second half of the chat becomes far more speculative. We talk about the future of of nature, of American prairie, other visionary ecological projects happening across

Subscription Model and Cultural Influences

00:01:17

Speaker

the world. it got really interesting.

00:01:19

Speaker

um So the first huge chunk of this conversation is free. The last 30 minutes or so are only available to paid subscribers. And the one thing I have always hated doing is asking people for money. But if you do like this podcast, if you want full access to my essays, Please do consider becoming a paid subscriber.

00:01:41

Speaker

Just go to kenilgunis.substack.com and for under $60 a year, you get access to all my podcasts, essays, all of that. um And at the very least, you make it easier for me to do long, in-depth interviews such as this one, turning a labor of love into paid paid labor. Please and thank you. So enjoy.

00:02:11

Speaker

This is the Out of the Wild podcast with Ken

00:02:30

Speaker

Okay, we are recording. Can I share what I've been listening to all morning with you, Sean? Well, let me guess. Little Feet.

00:02:51

Speaker

This is really good stuff. And I'm embarrassed that I didn't know who little feet is because i like classic rock and like, that's some like nice kind of CCR kind of steely Dan. I don't know how you would describe that kind of rock.

00:03:10

Speaker

They are probably more for, i guess, Gen Z and millennial listeners of music could be more Like, um let me think about this for a second.

00:03:22

Speaker

Probably dave Matthews type with just a little more raucous than Dave Matthews, I would say. Yeah. More of a... More late 70s, early 80s culture, Dave Matthews, when things were a little little wild.

00:03:36

Speaker

So, yeah, and that get the music the musicianship is incredible, and their live shows were quite amazing, I think. It's just kind of very buoyant, but also a little raw. Right.

Sean's Contemplation and Podcast Goals

00:03:51

Speaker

I asked you for a few kind of cultural influences over email before we did this, and you sent me a couple books like um Sapiens, another one called Decisive, a Short Walk in the Hindu Kush, and then Little Feet and Rai Kuder. And i I fed these into AI. I didn't put your name in or anything. this was completely um anonymous. And I said, could you give me a psychological profile on this guy? Can I can i give you its results based on your cultural favorites?

00:04:23

Speaker

Absolutely, please. Okay. um It says, psychologically, this is someone who holds romantic impulses in tensions with realism is socially observant, morally serious, but allergic to preachiness, enjoys solitude and reflection, yet believes life is fundamentally relational, is skeptical of grandiosity, I don't know about that about you, Sean, but is still drawn to big questions. At root, this is a person oriented towards meaning through lived texture. They are trying quietly, but persistently to understand how a human life ought to be lived,

00:05:01

Speaker

to be lived Not perfectly, not heroically, but well enough with attention, humility, and care. I'd say that's pretty good based on what I know about you, which isn't much, but I read your book, and that's kind of the attitude I i picked up. how How does that resonate with you?

00:05:17

Speaker

Send that to me. That's amazingly accurate, actually. I like that. Better than I could have said it myself, so... Yeah, I'm going to send it to my kids and see what they think. that's that's how That was actually, it boiled it down. ChatGPT offered quite a bit more analysis. Yeah, that's cool. That's nice. I was up in Montana recently. I walked across and kayaked American Prairie.

00:05:38

Speaker

What do you listen to? Because I know you have to go on these long, four-hour long drives. Are you listening to podcasts? Are you listening to Little Feet? What are you doing on those long drives? Yeah.

00:05:51

Speaker

It's a good question. know, it's, um maybe this will seem like a strange answer, but the way my brain operates is I'm always looking for to be vetting ideas with other people to see if two or more of us can try to to, each of us has a piece of the idea that is attractive. We can't quite put the whole together.

00:06:16

Speaker

When I have been on the reserve, it often is, I'm walking with people or sitting outside around the fire. We're taking long drives from one piece of property to another out there.

00:06:27

Speaker

And

Challenges and Philosophy of American Prairie

00:06:28

Speaker

we're discussing these ideas and it begins to gel. And then when I leave and I drive and I have quite a long, you know, four or five hour drive by myself coming back, uh, I have all kinds of podcasts I listen to. I like lots of different kinds of music and I end up, I go, okay, after I think this thing through,

00:06:46

Speaker

ah that we were talking about for the last four or five days with all my colleagues, I'll put on something so I don't get bored. And i can't tell you how many times I've arrived home five hours later and ended ended up turned I never turned anything on.

00:06:57

Speaker

oh It is digesting and synthesizing what everybody else said and trying, it's like moving a piece of puzzle around on a table and I've got absolute quiet. There's no traffic, absolutely no traffic, except maybe a car, eight or nine minutes or something comes by.

00:07:14

Speaker

coming towards me, you know, because beautiful, beautiful country, huge skies, might sometimes it's stars, sometimes it's depending on the night or day. And I'm trapped and nobody can get to me because it's really dead cell service most of the time where I'm going through.

00:07:28

Speaker

It's quiet. So that's mostly what I'm doing is being quiet and trying to put together, take all these really great pieces of conversation to move to a new idea that'll get us to the next place in the project. That's what most often happens.

00:07:41

Speaker

You make it sound very pleasurable. So you don't it doesn't sound like you resent having to get in that truck and be like, oh man, it's another four-hour haul. No, I've done it. you know I don't do it so much anymore. I'm up there maybe three, four times a year now, which is quite light compared to when I was 17, 18 years when I was... um In my role there, i would be more like once a month um ora or more oftentimes and be up there for four, or five, six days at a time.

00:08:14

Speaker

so I've been, this I've done this well over a hundred times 18 years, right? Yeah. I never get tired of that drive. I just don't. I'm not just looking at my watch and I wish I was home, et cetera, et cetera. know, it depends ah how harrowing the drive is. Sometimes it's black ice, which means you can't see it. Same color as the road, slick, you know, crosswinds and things like that. I'd rather be home and be safe for sure. But most of the time, just go, this is is a pretty amazing drive. Yeah, it's beautiful.

00:08:41

Speaker

my My nephew, Tristan and I, we just had some amazing drives because we had to do some food drop offs on our path. So we dropped off some food at Enrico and then in Zortman and Judith Landing. So we got to see the whole thing. And like every mile was just beautiful, especially when you see those breaks kind of at the western end of of the refuge. it's just It's just unreal. It's one of the grandest views you probably get in all of America.

00:09:08

Speaker

Yeah, absolutely. I should probably introduce you now now that we're six minutes into the podcast. Sean Garrity is the co-founder and former CEO of American Prairie. and if I get any of this wrong, just let me know, which is a giant wildlife refuge in the making in north central Montana, which I hiked and kayaked this past August, if I haven haven't already said that. He is the host of the Answers Are Out There podcast, in which he interviews leaders who've taken on bold conservation projects, and he's the author of Wild on Purpose, The American Prairie Story and the Art of Thinking.

00:09:47

Speaker

bigger i've been listening to your podcast um this past week which i really love because you're bringing in on these people who have all these innovative ideas and i don't know what podcasting is like for you but i love it just to have the conversations forget about like building my brand or selling anything or anything like that it's like it's having conversations that i wouldn't normally have what is it like for you

00:10:13

Speaker

Exactly that. I don't think I have a brand. No one's offered to pay me for my brand, that's for sure. one's paid me much for this either. It's a – what it does for me in these times when I'm with other people and they're fretting about the state of the world, just name whatever topic it is,

00:10:35

Speaker

ah food systems or politics or the environment or whatever. yeah There's a lot to be concerned about. And at least here, you know we're sitting in two very different places. I'm in the ah lower 48 in the US and our news is shaped designed to try to almost to try to get you upset. So you'll keep going back the next day and say, what happened yesterday that was even worse than yesterday? Kind of, yeah. Or to some tomorrow kind of thing. It's like, it's like watching a car wreck or something. You slow down to observe the car accident.

00:11:06

Speaker

And our news is bent heavily towards the negative. I'm talking about the U.S. now. And it doesn't really matter what outlet you're looking at, whether it's which way it leans or anything like that.

00:11:18

Speaker

So in this job, though, um I was able to talk with a lot of people around the world, mostly to try to get ideas from them where they're ahead of us in the world of rewilding, et cetera. And we could what parts of those ideas, if not the entire idea, could we port over into our work?

00:11:36

Speaker

and make our work progress more intelligently, smoother, easier, faster, cetera. And in talking to those folks inadvertently, I found out about a lot of projects all over the world that are very exciting and feeds feed one's optimism.

00:11:53

Speaker

And this was while I was at American Prairie. I wasn't recording it. I wasn't having a podcast anything like that. Then I thought, you know, when i finally had time after formally retiring from my role in American Prairie, at the time still being on the board and all that,

00:12:07

Speaker

And this podcasting stuff was taking off, you know, prior to the pandemic, actually. thought this could be, maybe I know how to get to people. i know how to find these projects because we made it ah a point to find these projects, projects to try to learn about things to make our project better. i know how to get to them, you know, triangulate through friends in Europe or Africa or wherever and land on these amazing projects.

00:12:32

Speaker

places, these projects get introduced to people. Why don't i build a podcast and bring that to the rest of the world so they can have some reprieve from all of the bad news, at least in America. i mean, I read The Guardian and Singapore Straits Times and other things too, but there's nothing quite like American news to...

00:12:48

Speaker

Get you upset. So can I, can I, uh, can I maybe be, ah um, somewhat of a reprieve from that? Maybe a bomb in a, in a world where this fire hose of news can be disturbing and you can listen to this and catch a break and say, you know what, there are people out there I've never heard of. That's the most important thing for me is you've probably never heard of any of those folks. I bet as you looked at all the folks I interviewed,

00:13:11

Speaker

they Most of them weren't familiar to you. And the more you hear about them, you just go what a fantastic person this person is that Garrity's talking to. And what an amazing project. who Who would have thought that up? And they're

Personal Reflections and Future Vision

00:13:23

Speaker

succeeding.

00:13:24

Speaker

So i want people to i want people to end the podcast and they come back if they listen to it while they're walking their dog or whatever. And they go that was a bright spot in my day. ah that bit of news. I now know about that 4,500 square mile new marine protected area off the coast of California run by indigenous people and the woman who's the head of the tribe, the Chumash tribe was doing it.

00:13:47

Speaker

And i have I live in the United States. I never heard of that project. you know So they're they're brightened. Their attitude is brightened up by having listened to these stories. That's the whole point for me. And it's fun. It's just fun when I run into people where someone says, hey, I just listened to that thing about Maine lobster fishermen starting to grow kelp off the coast of Maine or whatever it might be. You know, they go, that was i was so cool. I've never heard of that particular project. so it's a blast to bring that to people.

00:14:13

Speaker

feel like everybody should have a podcast. Like everybody should have a therapist. Like it'll just, it'll just do you some, some good. And I hadn't heard of most of those ah folks and the projects they were working on. And some of them are huge.

00:14:25

Speaker

Like that Native American woman you had on, that was like a 5,000 plus square mile. It's big. Off the coast of what, California? was just like, yeah wow, that's, it's enormous.

00:14:38

Speaker

Biggest, biggest new marine protected area in the United States. And most people in the U.S. have never heard of that project A lot of people haven't heard about the other native indigenous woman I talked to um from the Yurok tribe and the largest dam removal project in the world.

00:14:53

Speaker

off the Klamath River taking down four dams and like going over 200 miles of river run free again. And the salmon, they thought maybe it'd take them 20 years to find their way back up to the headwaters. It took them about four months.

00:15:06

Speaker

And that's, you know, that's a lot of people had never heard of the Klamath Dam Removal Project, you know, involved Berkshire Hathaway and Warren Buffett and the governor of California and led by six different tribes did it.

00:15:17

Speaker

You know, it's really cool. So it's got get those stories out there, you know? It's interesting for me to hear you say, you know, you're learning from other organizations, you're picking up tips from them, because in many ways, American Prairie has probably learned a lot and has a lot of wisdom to offer other conservation projects. And I don't know where you rank American Prairie on the list of kind of grand conservation projects. But from what I know, I mean, it it it deserve deserves a spot near the kind of the tippy top of that.

00:15:52

Speaker

Well, I think it

00:15:56

Speaker

was some 25 years ago when we started it. Yeah, the idea in our head was certainly a big idea. and a lot of people said, well, Don Quixote had big ideas too. And yours may be about as important as that, you know, tilting windmills.

00:16:09

Speaker

But after it started to gain traction and it looked like we would be, you know, heading in the direction of eventual success, it was a big idea. But these days, which I feel very good about, Rewilding has taken off in the last 10 years and it's hard to keep up with all the cool projects.

00:16:25

Speaker

ah Just yesterday i was on the with a guy named Mark Day with Alton Dial. Not pronouncing that sorry Mark correct, but they're building this thing three times the size of American Prairie on the grasslands of Kazakhstan.

00:16:36

Speaker

Amazing project, absolutely amazing project. And Alistar Scott, who runs the Global Rewilding Alliance, and I started going through some of their members in there just as just yesterday.

00:16:49

Speaker

a bunch of folks I'd never heard of or want to talk to. So it's, it's hard to keep up these days with the explosion, maybe hyperbole, but a rapid expansion of rewilding projects. And I travel a lot. I've been to many, many different countries And you go and all of a sudden you're there just a little while. i was in Thailand for five weeks with my wife and we're moving about slowly, you know, staying on the ground, moving place to place up and down the Malaysian Peninsula.

00:17:18

Speaker

While I was there, I always try to read local papers and stuff and found out, stumbled across Thailand's the only Southeast Asian nation where tigers, the tiger population is increasing.

00:17:29

Speaker

And I started reading about how in the world are they doing that? Because that's not easy. a crowded place like Thailand. Off there to the west, sure enough, next to me out Myanmar, they did it exactly w right with this incredibly intelligent collaboration between government officials, NGOs, small local NGOs, e etc.

00:17:47

Speaker

and putting together small, as you know, small protected areas and cooking them up with really intelligently laid out corridors. And it just keeps linking and linking and linking and their pop tiger populations are growing. Most people think tiger populations are crashing.

00:18:04

Speaker

Not so. ah Even India is being the export tigers and Sumatran tigers are on the on the upswing. But people don't know this because some places you have to just go and be there for a while to stumble across these stories.

00:18:18

Speaker

People don't know this and we're kind of blind and deaf to um a lot of the wonderful positive developments happening in the world, ah American Prairie. being one of them. And I wanted to touch on just kind of the the knownness of American Prairie and how you kind of perceive that whole thing. Because when I told all my friends, I'm going to go on an expedition across American Prairie, they're like,

00:18:45

Speaker

Where is that? What is that? nobody I told i told um a guest on this podcast who's a chair of an environmental studies program, and he had no idea where it was. But yet, you know you've raised many millions of dollars for this place.

00:19:01

Speaker

um You've given big talks to kind of big stuff. So there's kind of a weird kind of paradox there where it's kind of really well known in some circles, but it's not a household name to most Americans and certainly not um internationally. how do you How do you think about that? And do you want American Prairie to be a household name or is it kind of nice to be under the radar a little bit?

00:19:25

Speaker

he Well, I think the reason, ah thought about this a lot because as a leader of an organization, particularly when you're trying to fundraise. It's a rough start when you go fly somewhere to talk to somebody and they say I've never heard of it. Can you start from scratch?

00:19:41

Speaker

That burns up the first half hour of your lunch, you know, ah trying to bring them up to speed. So it was frustrating. And how can you not have heard of this? How fast we're moving. And yeah, now hundreds of millions of dollars been raised for it.

00:19:52

Speaker

It's surprising. you know, you you shouldn't feel bad about it. You're sitting in the UK, but I could go downtown in Bozeman, Montana with a clipboard and stand on the street. It's a little bit cold today, but on a warm day when there's a lot of people walking around, i could just ask them, hey, I'll give you a hat, a free hat, if you just answer my question. Have you heard about American Prairie? I bet more than 50% of the people not.

00:20:12

Speaker

And they live in Bozeman, Montana. Wow, even in Montana, okay. Nope, I could go down somewhere, right, my person who cuts my hair now, but if I just walked into a random place to get a haircut, I'll bet the person I sit down with, they go, you know, they start up a conversation. What did you do?

00:20:25

Speaker

Said I'm retired. What'd you do before that? talking about American Prairie. Never heard of it. Yeah. So here's, and here's my thinking on that, Ken. When I was born, I'm a lot older than you, obviously. You can see, ah and growing up through the 60s, there was less than 4 billion people in the world. That's one thing.

00:20:46

Speaker

And there is exactly three news channels, CBS, NBC, and ABC. That's it. That's the only place you get your news except your local newspaper. All right? Now, look at where news comes from and the amount of information you're expected to keep up on.

00:21:01

Speaker

I mean, I just mentioned Myanmar, you know, do you know what's going on Myanmar? That can take up your whole day to learn about what's going on in Myanmar. and A lot of it's horrendous. What's going on in Sudan and Yemen in ah Somalia land, which has actually got some rewilding stuff starting up now north of Somalia, other the country.

00:21:18

Speaker

ah you know, what's happening in Ukraine and all kinds of things, right? Depends on the topic you're interested in. But the the level of noise out there and what you're expected to keep up on is just extremely crowded. Now we're eight and a half billion people.

00:21:32

Speaker

There's a lot going on and all the vehicles that news has to travel on to land in your lap each day. It's overwhelming. It's really overwhelming. I don't think our brains are built for this kind of information flow.

00:21:46

Speaker

And the societal expectation that you should keep up on what's going on. At the same time, just trying to run your life, you know? So I think i don't get offended anymore. I just realize, wow, it's noisy out there.

00:22:00

Speaker

And trying to cut through the noise ah is an art. And to be recognized and known by the right kinds of people who can, for us, for American Prairie, I'm not not running it anymore and I haven't for many years, ah getting people to decide from a philanthropic standpoint to put funding into this as opposed to the hundred other things they've been asked to put funding into to come up on the top three of their list. You know um you have to be very thoughtful about how you spend your time because time is finite in addition to just trying to build a project, right?

00:22:35

Speaker

But keeping it going financially means getting to the right people and making sure they hear the right message and that it's not only is it believable, but you can back it up. You can fly them out there a year from now and say, look what we did with your money over and over and over again. And they're blown away with what you did and they want to give you more, you know?

00:22:55

Speaker

So yeah, it'd be nice if more people knew about it, not to become famous or anything like that, but because as a I'd like more people to understand it. And the reason I wrote the book, maybe I'm jumping the gun on some of the questions you have, but I want it to be, I would like it to be the project itself, an inspiration to some of these ah younger generations, ah you know, forget baby boomers, even Gen X, uh,

00:23:21

Speaker

They're, you Gen Xers are kind of in the late 40s, early 50s now. But the millennials, and particularly Gen Z, I think, who are gloing up growing up with climate anxiety that often morphs into climate nihilism. And, know, for young people, i'd like people to understand what happened with American Prairie because we started from scratch. Nobody was wealthy. It it needed, because the model, huge amount of money.

00:23:47

Speaker

And none of us ever fundraised before. and short story is we figured it out. It was really hard. We made tons of mistakes. Still painful me to think about the mistakes and much time we wasted trying to do running down false trails and and how it could have gone faster if we'd been a little bit wiser in execution in some of those parts. But in general, most days things went well and it moved forward and a small team of regular people, not particularly well-connected, non-wealthy people figured it out. And now it's one of the fastest moving conservation projects in an extremely contentious country.

00:24:23

Speaker

where everyone's got an opinion and a lot of it is why you shouldn't be doing what you're doing, why you should be stopped, you know? Yeah. Uh, why it's not a good thing. And it doesn't matter what it is. it can be a nature conservation or whatever else. It's amazing. Americans are getting so good at saying that, that, that should be stopped because of this. We shouldn't do that because of this.

00:24:42

Speaker

And we had plenty of it. So I'd like younger generations. I'd like it to be known better going back to original point. not for fame and recognition and pats on the back for us who had a part of moving along for a period of time.

00:24:56

Speaker

But so generations can start to feel a sense of optimism. What we can talk more about that today is ah it's a really important, I think, for young folks to feel like you can make a difference, you can exercise personal agency. And if you get to know your own values, your own sense of purpose, and understand how to set forth a vision for where you want to be in the coming years, and then start to apply that to something that matches your interests, let's not raise the bar too high and say absolute passion, but, you know, interests,

00:25:25

Speaker

You can do some big, super cool things in this world today. I'm kind of jealous because i'm not going to be around that much longer, obviously. And to have the tools and the resources and the access to information, the ability to call other people and get their help and advice, never in human history has it been so rich from that standpoint. And it wasn't like that 25 years ago, I can tell you. There was not a lot of people to talk to you about rewilding because it was just not a thing.

00:25:51

Speaker

um So this is the best time ever to start something that means something to you. Unfortunately, the way the news is coming at you in in such negative ways, this also is the one of the worst times to try to maintain optimism and not get depressed by what's going on.

00:26:09

Speaker

So I think I like the story of American Prairie, that's why i wrote the book, is shake that off. Don't let other people define your mood for you. Decide what's interesting to do for you, would feel meaningful, and go for it.

00:26:25

Speaker

And so that's why I want to tell the story we did, and this can be done over and over and over. This isn't about grasslands. This is about ambition to make the world a better place. your Your positivity, your optimism, which bleeds through the pages of your books, and I can see it you know in your face right now, is that is that a ah choice that that you've made?

00:26:46

Speaker

um is ah it a natural temperament, or is it kind of fact-informed? Are you kind of just looking at what's actually happening in the world and on the ground, and that feeds into that optimism?

00:26:59

Speaker

yeah It's both is's both. So first, and first part of that is, it's a choice. um, I ended up going to college totally by accident, it never intended to, because I wasn't a particularly good student in the younger, you know, kindergarten in United States is called K through 12, kindergarten through the end of high school.

00:27:20

Speaker

And had a lot of struggles for various region reasons. Fidgety, didn't pay attention, got lots of trouble, was younger than most people in my class because they started me at four, et cetera, all kinds of things.

00:27:32

Speaker

um Never intended to go to college. I was a weapons system mechanic working on construction and the union I was in went out on strike. So I was quickly broke. And thanks to my mom, she said, you ought to give college a try.

00:27:45

Speaker

I applied to Bozeman, Montana, and I don't know why, but they let me in. So i ended up getting a psychology degree. And i I still use it every single day. And I talked to, I learned about, you know, these classic Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers and all these different folks who talked about taking charge of your own destiny. And this was not pop psychology.

00:28:07

Speaker

um This was in-depth understanding how the human brain works. And we're mostly afraid of losing things. Our greatest fears are about losing what we already have. And we don't spend a whole lot of creative thinking about how could we move more in the direction of something that's more satisfying than what I'm feeling right now. and successful people are folks who can mitigate those feelings of protecting myself from loss. Instead, spending most of your time on that forward-looking thing.

00:28:38

Speaker

And somehow that really rang true for me. You know, Kennedy had been shot. Nixon was the president, got thrown out, impeached. a Vietnam War was, you know, 55,000 Americans were killed in that war. there's This was tumultuous times. And trying to decide, you know, can one person make a difference? Can one person actually carve out a satisfying, meaningful life was a big topic then.

00:29:04

Speaker

So it just hit it So i yeah, I kind of wired my rewired myself for that and that's how I'm going to decide, you know, what satisfaction, what success looks like for me.

00:29:16

Speaker

The other thing that keeps me informed that that informs my, my optimism because I go looking for ideas of where cool things are happening and what parts of those ideas can we steal and put together into something?

00:29:28

Speaker

Um, The second thing, though, is now i'm not trying to build really anything. um The time of life I'm in this particular phase. But I do enjoy keeping up on trends. And so, for instance, as you know, prior to the pandemic, just prior to the pandemic, quite a few different books came out. They were all it's kind of an interesting time, all kind of saying the same thing.

00:29:51

Speaker

We ought create a vision for the entire world on what, re rework our relationship to nature. Because right now, things are not going so well. This 2014 to 2019 or so. And one book kind of pulled it all together. it wasn't necessarily the best one, but it was pithy.

00:30:07

Speaker

And that came from Ed Wilson. It's called Half Earth. And he said, you know, we really ought to take on, at Ed, I've met him numerous times. He's actually got some YouTube videos on American Prairie.

00:30:18

Speaker

Super guy, passed away a few years ago. ah He said, you know, a cool goal would be, why don't we get back to where things were some decades ago, where about 50% of the world, terrestrial and marine surfaces are designated for nature and human beings can have the rest to do all their enterprises.

00:30:40

Speaker

It's more elaborate than that. I'm paraphrasing, of course. ah But that set off this idea of, well, what would that take? to get there. One, we should break it down into smaller increments. How about 40% of the world by 2040? How about 30% of the earth by 2030? That's where 30 by 30 came from.

00:30:58

Speaker

It's the first step on the way, on multiple steps to 2050. And then people started saying, you know, ah what if we all signed up to try? We don't know how we're going get to this destination, but it's hell of a vision. It's a great way to start. Hell of a vision.

00:31:15

Speaker

And what if we sign up for this? Well, now 192 countries out of the current 196 countries, depending on if you count the Vatican or whatever, that exist today, signed up to try to achieve 2050. That's pretty amazing.

00:31:31

Speaker

First time in history the entire world, is most of the world, 98% of the world has signed up to try to um to achieve one vision. Later on, of course, like any good strategic planning session, well, we can't boil the ocean here. We got to pick what are the most important things to work on?

00:31:45

Speaker

What's the, you know, the ratio principle, hold the 20% of the effort that'll give us 80% of the big big bang for the buck. And they narrowed down, you know, 30 ideas down to 15 and then down to 10, then down to eight, and then down to four.

00:31:58

Speaker

And now, you know, you hear David Attenborough and your a world there and many other people say, here are the big four things we got to work on to have any chance of getting to 20, 30, 20, 40, 20, 50.

00:32:08

Speaker

And those are stabilized global population, human population. Accelerate the transition to green energy. The third one is rewild everything you can and do it faster. And the biggest one by far is redo how we do agriculture, because that's the most destructive thing out there in terms of taking things away from nature.

00:32:30

Speaker

How we fish, how we farm, how we raise livestock, et cetera. And so when I started looking at those, I mean, those are that's great stuff. And it gets it's on repeat now in movies and documentaries and books, et cetera, which is good.

00:32:44

Speaker

That's how, you know, movements get started. And a lot of people are chasing those goals and trying to emphasize important work in those four areas. Is if you just, if you and I get off this podcast and we just check in on that, use whatever your favorite AI search engine is or whatever, if you don't trust AI, you know,

00:33:03

Speaker

Find another way, go to the library, whatever. um do some Download some you science articles or whatever. You'll find excellent progress happening in all four of those areas.

00:33:15

Speaker

Not uniformly. I'm sitting the US. We're one of the worst, or almost in some ways a backward country in that way. But we're only one of 196 countries. And I get around the world quite a bit. And it's pretty exciting when you look at it holistically or globally.

00:33:30

Speaker

What's moving in those four areas I just described is pretty darn cool. All of them need to go faster. But if you take the long view, 20, 30, 40, 50 years, to me it's looking pretty good If someone's thinking about 30 2030 or they're moved, they're motivated for you. it wanting by by something there's a ah passion behind that and i'm wondering what it is exactly

00:34:01

Speaker

for you is it wanting to live or, you know, having, you know, your, your ancestors live in a more ecologically intact environment? Is it wanting to feel kind of enchanted by everyday wildlife? And it usually comes from a place of some sort of ecological boredom or depletion behind that. And I'm wondering if, if that's kind of behind you in some way.

00:34:27

Speaker

Yeah, it's it's a really important question you're asking, understanding motivation. That's back to my accidental degree in psychology, which I wouldn't have gotten had that strike not happened.

00:34:38

Speaker

ah

00:34:42

Speaker

It's really important to try to understand why do we as humans do things? Why do we get and fired why do we get so fired up to try to make things different? And I got a, luckily, having grown up mostly in Montana, i got to do a stint in Santa Cruz, California with my wife, Kayla, and both our kids were born there, actually. And I worked a lot with different organizations as a consultant, organization development consultant.

00:35:05

Speaker

And they were all trying to make things, improve things. And in the book, I talk about one that quite a number of people, it's getting be an old analogy now, but Moore's Law came from Gordon Moore, who's one of the founders of Intel.

00:35:20

Speaker

that the amount of transistors you could put on a chip, which makes it run faster, do more higher level computation, all that kind of stuff, will double roughly every two and a half years.

00:35:31

Speaker

And people said, it sounds good, Gordon. At what point does that, you know, taper off? And he goes, never. And it's been decades and it hasn't changed. It's an attitude about continuous improvement. And once you adopt that attitude about continuous improvement about something, some of them do that where they're running. How far far can I run? You know, can I do marathons and stuff? It's just, it's taking on an attitude of continuous improvement.

00:35:55

Speaker

For Gordon Moore, was about computer chips. I couldn't care less about computer chips. And how do you make them run fast without melting the entire computer and all that kind of stuff? It was a game. And there's a lot of people at the time Silicon Valley, was there in the eighties and early nineties that just love the game. It doesn't matter what it is, try to make Bluetooth work better or something.

00:36:15

Speaker

So I'm not sure it's any more complicated than that for me, Ken. ah I decided i like the continuous improvement thing. i always wanted to see if year by year, I could be a better dad. I have two kids and I've got two grandkids.

00:36:29

Speaker

What does it mean to be a really great grandparent to these grandkids? What what can i provide? Their parents are providing plenty for them as far as getting them to school and they have enough clothes and all that kind of stuff. what's How can I be a better granddad or whatever?

00:36:43

Speaker

i i like the continuous improvement idea. it's fun. Um, and i thought, well why don't I apply it to something that i really care about? And that's wildlife, nature, environment, because I know what it does for people like you and your nephew walking across.

00:36:58

Speaker

I know that was arduous and was hot on some days and you probably saw a mosquito or two, but you also saw the Milky way at night or looked at the cosmos in the way most people in the world don't have the privilege to do.

00:37:09

Speaker

Right. Cause of that just unbelievable, unbelievable darkness. So trying to push the idea of, hey things are kind of out of control with our species. our we We just keep taking up more and more land to feed our livestock, feed ourselves, build our highways and build our airports and stuff.

00:37:27

Speaker

But what are we doing for future generations? It's not great. And where where nature is losing rapidly. And there's a way to bring that back, I think, and flourish and prosper ourselves as a species if we just look at doing it differently.

00:37:44

Speaker

ah So that was, I wanted to be involved in the con continuous improvement world in a topic area that meant a lot to me. And I could have done it lots of other things that need improving that are equally or very, very important. you know so That's interesting for me to hear because i thought maybe part of your motivation is you know you want to go out into this prairie meadow and raise your arms in the sky and twirl around and you know have like like this Lewis and Clark

00:38:17

Speaker

Serengeti experience. um And I think that's kind of what I want. you know I used to be a park ranger up in the gates of the Arctic National Park, which is a pretty much intact um ecosystem. And I just...

00:38:32

Speaker

felt a sort of high from, from the sublime and seeing a herd of caribou and seeing ah a moose in the woods and a grizzly bear. And I know what it's like not to have those things in my life. So that's kind of one of my motivations for wanting these things.

00:38:49

Speaker

Um, I, I do the, I do that it's for myself personally, but I live in Montana. I guess we hang up, I can, it's too cold to get to my bike, but I get in my car.

00:39:00

Speaker

my little electric car and I could drive 15 minutes and be in the woods and have a decent, decent chance of seeing at least some deer. ah walk a little further, some elk bears are sleeping right now So, um,

00:39:16

Speaker

I am very privileged to have quick access to that kind of thing, but I've also, it's not just about Montana. You know, I've been diving off the coast of Panama have and, you know, tromping around all through Southeast Asia quite a few times in remote you know areas there where there's a few people and lots of wildlife.

00:39:40

Speaker

Been out of the ocean a lot to know what that feels like to be far, far away from land and feel very, very small you know, in a marine environment and seeing the, you know, seabirds and everything.

00:39:51

Speaker

and i' I've gotten to go get around quite a bit Africa. And it doesn't matter where, what the biome is, water, terrestrial, doesn't really matter. Having those experiences, it is selfish because it's unbelievably rejuvenating, just feels like an amazing privilege.

00:40:06

Speaker

So I do want that for other people. i have grandkids now. I feel like I should do the best I can to try to make sure there's still space left ah for them to have the same kinds of experiences.

00:40:18

Speaker

And if we don't get after it, it's not going to be left because left to our own devices, we will take it all. We'll take it all for our needs. We'll plow it up. um We'll, you know to grow monoculture crops, to feed our livestock or whatever, we will take it all. There's no restrictions on where we go and what we do, really.

00:40:39

Speaker

So, or very few, not enough restrictions. So... you know You have to play offense on this stuff is how i feel about it. Let me back up for a second, if you don't mind, um because you in your book, you kind of go back to your your early childhood and your past, and and there's always linkages to your time at American Prairie. I'm thinking of the passage where you talk about your mom and dad selling silverware. Yeah. And I know you would eventually have to do a lot of selling of American Prairie, you know, getting people to be interested in it and getting money through fundraising. Fundraising, by the way, sounds about like the last job in the world I'd ever want to have. um But first of all, can you tell me a little bit more about what you learned from your your parents and and selling that silver? war what What's the art of the deal from them?

00:41:32

Speaker

Uh, I'm the youngest of three kids. And when I was, you know, you don't have much awareness, but my parents told me what was going on when I was three and four years old. My dad worked for the Boeing company, but he actually started off sweeping floors in their big, in, uh, in North Bay, Ontario, Sioux, St. Marie, Michigan, different places.

00:41:52

Speaker

And I worked his way up to supervisor in warehouses and stuff like that. didn't make a whole lot of money, but he had things he wanted. and what he wanted was a used fishing boat and a used 35 horse used motor so he could fish.

00:42:07

Speaker

He didn't make enough money with three kids, um, to buy extras. So in those days, there was a lot of stuff that got sold door to door in the evenings. This is in the early sixties.

00:42:20

Speaker

And so one thing is you could come home from your day job and then have dinner and then go out afterwards in the moonlight. um ah With ah your own job, you could sell Amway. You could sell all kinds of stuff.

00:42:33

Speaker

But my dad, he would change his clothes after dinner and head out and he'd be gone for two hours in the evenings. And he'd had this really beautiful briefcase and he'd open it up on the porch and say, I'm selling silverware. People would invite him in.

00:42:46

Speaker

And they'd sit down they'd say, well, we'll take a set of those salad forks and stuff like that. and that's how he made extra money and he got a boat. And then my parents wanted to build a cabin or buy a small, very inexpensive piece of land in Montana. This is years later. And I watched them do the same thing.

00:42:59

Speaker

my mom sold Avon products. i don't know if you've ever heard of Avon, but it's, sort of you know, perfumes and things like that out of our house. So they would have parties at our house where all their friends would come over and there's catalogs and there's all this perfume. And my dad's serving drinks, you know, gin and tonics and stuff.

00:43:16

Speaker

And I'm just watching these two and they were able to buy product. very inexpensive piece of land is probably, I don't know, $9,000 or something. At the time, there's a lot of money for them, huge, but they did it through moonlighting on top of their day jobs. My mom was a social worker for the welfare department and my dad was working still in the blue car world and at Boeing.

00:43:38

Speaker

But these evenings they worked together as a team and they pulled it off. And what i learned was it doesn't matter what you're selling, is if you want something to happen, there's always a way to do it. You may have to give up your evenings or your Saturday mornings, but there is a way to make it happen if you think in the innovative ways and and also rely on great teamwork. They get along very well in the way they did that. so Rely on teamwork. And the gin and tonic too. That's probably a key component of the sale.

00:44:08

Speaker

Endless. Endless. Yeah. the bar but It was a hosted bar. It was open the whole time. Yeah. My mom sold a lot Tupperware. That's for sure. so So fundraising, you know, I haven't explained to the listeners how American Prairie has built itself up now. you have to, American Prairie has to buy private land off of willing sellers, whether farmers, ranchers, whatever. And sometimes you get um leasing rights to to Bureau of Land Management land as well. So you need to raise a lot of money to buy this property. So fundraising, is it as bad as it it sounds or is there is there some fun in it as well?

00:44:50

Speaker

What's your attitude towards fundraising?

00:44:54

Speaker

Uh, my attitude was not good when we started cause I'd never done it before and just building the project itself and figuring out all the intricacies of making it go well in a high quality fashion as you unfolded the thing over the years seemed like enough demand on me to do, think about that and build a proper team to address that over a very long period of time.

00:45:14

Speaker

And I've come from, i made ah one big mistake, in mini and many came after that. But I assumed that it would be very similar to for-profit enterprises of which I had a lot of experience working around the world, um, with a company we built in Santa Cruz, uh, three of us. And i thought, you know, all right, I'm going to be the main leader here and I'm going to have to figure out how to do some fundraising even but i've never done it. I'll ask a lot of people for advice. I'll read every book I can get on it, which that did occur and just start muscling my way along and try to get better through repetition and familiarity.

00:45:53

Speaker

Um,

00:45:56

Speaker

I did get better at it for sure. but what I was hoping was what I saw in early stage companies, eventually you can hire yourself a senior vice president of sales.

00:46:07

Speaker

And then as a leader, you you can't really forget about it because you got to have a weekly meeting. You know, how's it going down there in the Southern region? How's it going in the, our European markets and stuff like that. How we, let's check in.

00:46:19

Speaker

But the person who sweats it and stays up all night is, ah you know, worrying about the next quarter and can we close the next quarter with some profit or whatever. is the VP of sales and her huge team of salespeople, you know, wherever she has people deployed. And the CEO, it's just a small portion of your thought process.

00:46:36

Speaker

And what I realized is in nonprofits, kind of no matter how big they get, you don't really get to do that. You have to be in the game. Is that right? So you're always kind of involved in it.

00:46:48

Speaker

Well, as best I can tell, and really important for our listeners, I've run exactly one nonprofit. That's my data point. i have not I'm not an expert in this still today. But a lot of people I talk to who are running much bigger enterprises than American Prairie, far bigger, they said, John, it never changes. You always got to fly to London or somewhere to go have dinner with So-and-so to tip it, you know, take it from almost have the gift to over the gift and get a handshake.

00:47:17

Speaker

A lot of times a CEO has to be there. And so you have to plan, you have to think about how are you're going to do it? What's it going to look like? What are you shooting for? You're shooting too high, you're shooting too low, leaving money on the table, all the strategizing. And it's just, it's a huge thing.

00:47:31

Speaker

So, yeah. And this is, you know, our fault. We picked a model. You can do conservation other ways. You can use conservation easements where ah in America, don't know how to describe this so it works for everybody, like all your listeners around the world, but you can –

00:47:52

Speaker

Go to a landowner who has private property and say, can we interest you in a conservation easement? What that means is if you promise not to build out any more infrastructure, just keep your house and your barns and whatever else, but don't put a subdivision here of homes and condominiums, things like that.

00:48:10

Speaker

We can give you a break, very big break on your taxes, actually not just this year, but over the course of maybe four or five or six years. These can be worth in the area hundreds of thousands of dollars if you're willing to sign all these agreements to not do certain things on your property and leave it kind of as is open space and all these different kinds of things.

00:48:30

Speaker

That is a conservation tool that is um quite popular the United States. But what we wanted to try to do, our criteria for success with bringing back abundant wildlife and all the things we considered, and we thought, you know what, you guys, we got to own it ourselves. We have to own it ourselves.

00:48:51

Speaker

And... That's great because you have the power to decide what happens. don't have to control other people over and over and over again to operate or behave in different ways.

00:49:02

Speaker

And the downside is that's hideously expensive to go as big as we we're trying to go um and to somehow find the money around the world to do it. With all the huge amount of competition for philanthropy out there.

00:49:18

Speaker

And conservation is not very high on the list of what people give prop give gift to you. They give money to football stadiums. They give money to their churches. They give money to a lots of other things before. Conservation is way down in the list.

00:49:29

Speaker

So you're kind of digging for scraps there. it's There's risk baked into all of this. And if I'm wearing my English major hat, I'd say that your book is...

00:49:42

Speaker

it's There's a huge theme of risk in the book. You're always considering a risk. You're always taking a risk. Like even the episode where your wife, Kayla gets um sucked beneath some rapids on a kayak trip. And what was she under the water for like eight or nine minutes? I don't know how anybody could survive that. um yeah but there But there's risk kind of everywhere. Like, do you see yourself as a, as a risk taker?

00:50:10

Speaker

I don't think take, find myself taking risks that I haven't thought out well. And so I'm voracious about learning, always learning new tools for taking more intelligent risks.

00:50:24

Speaker

And I think sometimes people say, well, should I move across the bag my job and move across the country to take this other job? And they'll get a piece of paper and draw a line vertically down the middle and say, what are the pro pros and what are the cons?

00:50:36

Speaker

And they'll list out a bunch of pros leaving this job and moving across the country ah across the UK or wherever to take this other job, move my family, whatever. And here are some of the cons. And that's about as far as they get.

00:50:49

Speaker

But risk-taking really has a lot more sophistication to it than that. It has to not only just have cerebral thought processes, which are those two lists, there's a big emotional component in it.

00:51:00

Speaker

There's a lot to think about. What do I have in terms of resources to what if it all goes sideways? How can I recover? Really thinking that through seriously. So if the worst case happens, do you have the right resources or skills or attitude or whatever it takes to actually recover from it? In other words, you're not going to die.

00:51:19

Speaker

Even if it turns out to be great decision, you go, well It seemed like good idea at the time and now we're over here. It just didn't work. um As long as you can recover, figure out ah figure out ahead of time that you have a good recovery strategy should it not go well.

00:51:35

Speaker

There's lots of things to think about. That's why I put that chapter in there about how to take better risk taking. I think a lot of people will not make even a job change. Like from, say, you're an attorney right now and not very happy in a big law firm and You're doing 70, 80 hours a week, et cetera, and making lots of money, but maybe it's not as fulfilling as you thought was going to be.

00:51:53

Speaker

And you're thinking about jumping into conservation, for instance. I make that analogy quite a bit. That seems like a big risk when you've got a mortgage, you're saving a for maybe higher education for some people who want to do that for their kids, you know, safer college and things like that. Not everybody, but all the it feels like a big risk to take the leap into conservation. Yeah.

00:52:15

Speaker

Happened to me, and my my salary was cut in half, but um there's no way I'd ever look back. it's a It was a very good decision. It turned out to be a really good decision. but I think we don't get taught, think about, know, from the time you're five years old until you're 12 and leave high school, which is what most people in the United States, that's as far as you get, most adults in the United States. About 35, 36% ever achieve a four-year college degree.

00:52:41

Speaker

So the highest level of education here is high school. And nowhere in kindergarten through 12th grade does anybody, is there a class on risk? They'll say you need to take a foreign language, you definitely need to learn German, but you do learn absolutely nothing about taking risks. And here we're in a capitalist society where risk taking is needed and no one tells no one tells you how to do it.

00:53:04

Speaker

So a lot of people sit in jobs they don't like anymore because, ah back to that thing about loss. Most people, the biggest motivation is to not lose what I already have. Even if what I have feels suboptimal, I don't want to put it at risk.

00:53:20

Speaker

because And there's a great book called Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman, who just died a little while ago. Highly, highly recommend that book because it explains this. And if you can shift your thinking to being focused on how do I get myself excited about this possible next better thing, better situation for myself, for my family, or whatever, as opposed to spinning and spinning and spinning on protecting myself and not losing what I've already achieved,

00:53:46

Speaker

ah you might have some really exciting times ahead of you. So I try to write about that. Just listen to Kahneman and other people like them that can articulate this better than I can. They're absolutely dead on.

00:53:57

Speaker

is Learn to take intelligent risks and practice it. Get desensitized to taking risks. Not crazy things, jumping off a cliff with a too small parachute go paragliding and things like that. I'm not talking about that.

00:54:11

Speaker

Things that may take you to a more satisfying existence. That doesn't mean being richer. It means feeling like, you know, just what I'm doing now feels truly important.

00:54:22

Speaker

Yeah. I think a lot of people want that, but they don't want to lose what they've gained. Yeah. that's a trap It's a trap. So you've you've kind of figured out the art of the risk, almost to the point where the risk isn't even a ah risk anymore. It's something you've kind really picked apart. um and And, you know, before this, you were a consultant, you were working in Silicon Valley. I'm sure you've worked with you know countless organizations. And I'm wondering what you think about like when an organization begins, does it kind of need that someone or that team that's kind of very bold, visionary-minded and

00:55:03

Speaker

calculated risk taker? did you know Did American Prairie need that sort of attitude starting off, someone who's going to break a few eggs to to make an omelet? And after that, does something else need to happen once the place has been established and matured and maybe maybe you don't need that boldness and um risk taking and visionary? Do you know where I'm going with this question? Mm-hmm.

00:55:30

Speaker

I think so. So tell me, but give my answer. Tell me if i was where you're going, where you're you're headed there with it, where your intent is. But i got very lucky. Well, first, my answer is yes. I think at some, with some, in some instances, depending on what the task is, it is very helpful to have someone who's willing to break some eggs or an,

00:55:54

Speaker

American parlance, break some dishes, pull on a china shop kind of thing. I think the yes. And okay, we'll break some dishes. We'll fix them later, later but we're moving ahead.

00:56:05

Speaker

Or another analogy is we're going to keep keep going in our boat and we may take a lot of holes in the hull. As long as most of them are above the waterline, none are below the waterline, we'll patch them later. We've got a good welder on board.

00:56:17

Speaker

When we hit some smooth seas, we can throw her over the side and she can weld up those holes. ah But let's keep moving forward. You need someone of that kind of attitude for sure often. got very lucky by being able to work in a lot of different industries and seeing people pull off amazing things. One of my favorites early stage biotech.

00:56:35

Speaker

Some of the things people were chasing to try to make things better for HIV, for malaria, for breast cancer, and all these kinds of things they' trying to solve. Making artificial human skin. So seven-year-olds who'd been burned in a fire would have, you know, can this beautiful supple skin to repair their bodies with. Oh, the stuff I got to work in, what their their business was, and they actually made progress with stuff that nobody thought could be solved. They were solving it.

00:57:02

Speaker

And they're solving it incrementally, detail by detail by detail. These are amazing bench scientists. These were in Southern California, whatever. I saw the same thing in technology, but in other kinds of industries as well.

00:57:14

Speaker

And what i came to believe is if you get the right people in your team, part of it's their attitude or their skills or their ways of looking at things, which are different than mine. They'll look through a different lens at a problem and you can bake into the culture, the demand you have for your culture, good teamwork and listening and collective problem solving and all that. As long as you can build the right kind of culture and get the right individuals that together it doesn't really matter what problems going to come up they will figure it out they will they will solve it and i got an enough experience being around teams of all different kinds of industries where that occurred sometimes they would stumble and get stuck uh usually interpersonal problems things like that that's what we got called in to get things oftentimes to get things unstuck and keep moving forward um

00:58:05

Speaker

But I got to see it. and I realized this can occur if I can put the right people together and create a very specific culture that if you don't want to be a part of this culture, go work somewhere else. as these values around execution, around innovation and optimism, around teamwork, openness with respect, all these things, these six or seven facets that shape a culture. If you can get terrifically bright people to come in and be interested in operating inside a culture like that, you're pretty unstoppable as an organization.

00:58:38

Speaker

o And a founder can depart and it keeps cooking. That's a really cool thing. It appears like that has has happened. Absolutely. absolutely let's Let's stick with the problems for a second. And this is ah one digression into the politics, which I don't even think is going to turn into a politics political question. But um i'm talking I'd like to talk about Montana Governor's Greg Gianforte. I don't know if that's how to pronounce it. But he and four congressmen, they sent a letter to Interior Secretary Doug Burgum

00:59:12

Speaker

And i I think to kind of boil it down, it was to keep bison off of the land that you you lease from the Bureau of Land Management. Is that it in a nutshell? ah Yes. It's to challenge the decision that was made by the Bureau of Land Management to allow American Prairie to graze bison as livestock on public lands of which for folks who aren't in the States, I know a lot of people are not from the States listening to this. Um, the Bureau of Land Management is the largest land operator in America.

00:59:51

Speaker

think I'm going get this close about 280 million acres, which is a lot. and don't know how to translate that exactly to hectares, but, um, Uh, you can buy a base property, which is in your private property. Let's say it's 5,000 acres and you can accumulate. You can also then have the opportunity to lease an additional 5,000, 10,000, 15,000 acres of public land.

01:00:20

Speaker

Doesn't mean you own it. Doesn't mean you can keep other people public, other people off of it. So there's a whole freedom to roam aspect to it on public lands, which is really terrific. But you're allowed to graze a livestock animal on that. And there's six. There's llamas, goats, sheep, cows, horses, and bison. Those are all registered livestock animals.

01:00:39

Speaker

So oftentimes when we get this, we'll say we want to take cows off, beef cattle, and put on bison. It could have been horses, take the horses off, put on llamas, or llamas off, put on goats.

01:00:50

Speaker

And there's a process for doing this. the Bureau of Land Management studies extremely carefully making sure that you're not what you're asking is not going to cause any adverse effects for the public because they're doing this good.

01:01:02

Speaker

They are trying to do right by the general public. They're not trying to emphasize... what you want, they want to make sure you can, but if you want to put these bison on or these llamas or goats or whatever you're trying to exchange to, you're not going to take away from the enjoyment of these public lands by the general public because that's who it's for. It's not you and your bison or you and your mining or you and your life you your forced you you're a forest products business, whatever it is. This is the public's land and you're borrowing a little bit

01:01:33

Speaker

um through this lease, but we need to stand up for the public. And so we pass that and they've got a decision. Yes, we're fine. and then, um but some particularly of certain industries, oil and gas, ah livestock, mining, et cetera, are not pleased sometimes you know sometimes with that, just how it goes in the States, you know, depending on the industry. Yeah.

01:01:59

Speaker

and so look at the The decision is being challenged. Nobody's suing us. it's challenge Did Bureau of Land Management do the right thing? That's basically it. And their position to me, just to speak frankly, seems ridiculous. I'd like to see...

01:02:13

Speaker

I'd like to see bison be able to go on that land, whether for reasons of conservation or or livestock or whatever. But I just want to ah read what they wrote in this letter. for us um For us, a decision in favor of American prairie will reshape the entire landscape of our state.

01:02:31

Speaker

Montana's most profitable economic industry for decades has been agriculture. American Prairie threatens the economic vitality of our most important industry, decreasing agricultural production revenue and directly impacting industries downstream that shape our overall economy.

01:02:51

Speaker

Now, my first reaction to that as just someone who's kind of watching things from afar is just like, for fuck's sake. I mean, come on. Like... you're You're embellishing, you're exaggerating, you're discounting American Priory's role in the local economy.

01:03:08

Speaker

And if I was on your team, if I was on the American Priory team, I think I would have been able to like hold my tongue that one time. But if this thing happens like a thousand times,

01:03:19

Speaker

you know, and i might kind of lose self-control one of those times and and say that thing over social media or or whatever. It seems like American Prairie has never made that mistake. And I don't know your whole 25 year history, but I'm kind of just wondering, like, how is that? If that's true, how is that the case? How does how does your team have so much discipline with with these big headaches sometimes?

01:03:46

Speaker

Well, we take medication, lithium and stuff like that. and I'm just kidding. i'm just kidding ah You got to keep it together for sure. I think because we take the long, long view.

01:03:58

Speaker

And so we're a big believer in sometimes it's three steps forward and two steps back in terms of progress for the project, which is, can be exceedingly frustrating, particularly when sometimes it feels unfair, but overall,

01:04:13

Speaker

We keep moving forward on all the important fronts or in business, you call them critical success factors, things that have to go well. And you really would like to not see them go not well.

01:04:24

Speaker

We do pretty well, or I should say, I keep saying we, because still seems like I'm around, but and I'm not, it's important to know I'm not running it, but they now are really good at keeping all the critical success factors in mind and making progress Sometimes it's not spectacular and bright and shiny progress, but it is important progress nonetheless, taking the long view, sticking with it, and realizing you can't win every single day.

01:04:53

Speaker

It seems liberating. It seems like, oh, there's going to be a couple steps backwards. This is one of those steps. We're going to take another couple forward. I can see kind of the the liberating mentality in there.

01:05:06

Speaker

I've got some rapid fire questions for you, Sean. You can elaborate if you want, but you can keep them short too, if that's all right. Is that all right? Yeah. What's um one great American prairie memory that stands out as a point of pride to you?

01:05:23

Speaker

I was driving north on this 55 mile long road that goes north, a gravel road that goes north up to Malta. And I had to be to First State Bank to talk to a a banker there.

01:05:35

Speaker

And some things had happened early in the morning with some bison stuff. And I didn't get in the car as soon as I should have. So I'm bailing up the road. I stopped by a campground. And one of our campgrounds that we built. And there's a couple. Nobody else in the campground except one couple.

01:05:54

Speaker

And the the husband was sitting, typical camping scene. He's in a chair. he's got a big floppy hat on. He's reading a book, enjoying the birds, all kinds of birds around him, sprigs, pippets, or um oh

01:06:09

Speaker

meadowlarks and all different kinds of birds around him. So just having a nice morning in this campground, which made me feel good. His wife, or I guess a female companion, was over on a little bit of a slope and looking down. And there was eight or nine 10, 11 something, bull bison, all big bulls.

01:06:26

Speaker

This was in the spring, green grass, and the bulls kind of get pushed away because the females are off in kind of these mother groups that have new calves with them. They don't want the bulls around. So the bulls just kind of hang out, nothing to do during this particular month.

01:06:38

Speaker

And they're all they're all lounging around too. And this woman has a little Instamatic camera, is taking pictures of them. And I can't hear what she's saying because she's far away and she's turning around around talking to her male companion sitting in the chair, they look like they're in their seventies or so have an old van they're camping out of with a local license plate.

01:06:55

Speaker

And i stopped and looked at and I said, this looks like what have seen since I was a kid in Yellowstone Park. I still live about an hour from Yellowstone Park. So I'm familiar with the scenes there. People just simply enjoying nature.

01:07:07

Speaker

Absolutely dead quiet out here. They're staying in a campground that costs them $16 a night. It has water, it has power, all this. ah And they can do they can stay here all day doing what they're doing. And they're looking at these magnificent 2,000-pound animals lounging on this little hillside. They're like 100 feet away from her down the slope.

01:07:26

Speaker

And she can stand there observing them as long as she wants and take as many pictures as she wants. But the bison are also free to do what they want. They can get up and walk 9, 10, 11 miles one direction on a fence ah if they want to go sit somewhere else.

01:07:38

Speaker

And it's just this bucolic scene that I thought, it's two people. It's just a little group of 11 bison. But the sound and what this morning feels like and the air and the smell of the sage you rescue of spring, it's very pungent at that time.

01:07:54

Speaker

I said, this is like a miniature Yellowstone-like experience. This is exactly what we wanted to create so people could enjoy the heck out of it and have a time out of time in nature like this with no sense of rush. And all around them, but the bugs, the flora, the birds, um the big young the big char charismatic animals, it's all there for them to sit there, and enjoy, and relax.

01:08:20

Speaker

And I just sat there in the truck, which maybe even later, but I didn't care. I was doing a little savoring thing for about, honestly, it probably lasted eight or nine minutes. It was not a two hour thing and I didn't get out and do yoga and meditate stuff like that.

01:08:32

Speaker

And then I fired up the truck and took off. I'm sure I was late for my meeting. But I did that over and over and over and over when I saw certain things happening and I have tons of them in my memory, which really the frustrating things like that letter, all those things fall away and what stick are those moments of s savoring progress.

01:08:51

Speaker

What a nice portrait you've just drawn and it's a portrait that wouldn't have existed if if you hadn't done what you'd done. So not only is it a beautiful thing to see, but it's also kind of a validation of the decades of of work you've put into it.

01:09:08

Speaker

One great non-American prairie memory that stands out as a point of pride. In any particular topic? and I guess anything.

01:09:21

Speaker

It's way too broad, but does anything come to mind? Well, God, it's just, I've had a very fortunate existence, I think, maybe holding my young grandson, Louis, for the very first time when he was, teeny tiny baby and then his little sister, Simone.

01:09:38

Speaker

Nothing quite like that. That's about as, you know, the feeling you're sitting there and you're getting fairy dust sprinkled all over you. That's hard to beat.

01:09:49

Speaker

Honestly, sometimes when I'm doing these podcasts, like the ones you've been listening to on the, that I'm taping people, when I'm done, And it all to turn off all the microphones, you know kind of shut down the studio like you and i are sitting in here.

01:10:03

Speaker

And stand up and go get myself another cup of coffee and go stand out on the deck and think about that person I just had the privilege of talking to. And i'm not going to I'll probably go visit their project in Scotland or California or Namibia or wherever it is.

01:10:17

Speaker

Probably eventually get there um because it's so interesting. and Just the chance to meet them in person to be so cool. um But the privilege of your being able to talk to these folks and then standing there knowing that as soon as they hung up, they jumped right back into it, their thing, what it is they're trying to make happen. And they're barreling ahead. They love the challenge.

01:10:39

Speaker