Become a Creator today!Start creating today - Share your story with the world!

Start for free

00:00:00

00:00:01

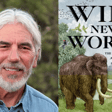

Adam Weymouth on the Return of the Wolf

Adam Weymouth is a British author of Kings of the Yukon, about his 2,000-mile voyage down the Yukon River, and, now, Lone Wolf: Walking the Faultlines of Europe, about his 1,000-mile hike following the path of a wolf. We discuss…

Subscribe now

- Are we better humans when we’re on journeys?

- Why have there been so many more deaths (wolves killing humans) in Europe than in North America?

- Ken has a bone to pick with Disney: Why would a nature-loving production company depict wolves in such a retrograde way—in 2013?

- Are old tales of rabid wolves the reason why Europeans are so anxious about the wolf?

- What can farmers do to protect their herd/flock from wolves?

- Should wolves be re-introduced to the U.K.?

- Can a wolf swim the English Channel?

- What is a lone wolf looking for?

Some of Adam’s favorite travel books:

- Adam recommends The Rheingan Sisters:

Transcript

Introduction to Adam Weymouth

00:00:05

Speaker

This is the Out of the Wild podcast with Ken

00:00:18

Speaker

Adam Weymouth is a British author of Kings of the Yukon, about his 2,000-mile voyage down the Yukon River, and now Lone Wolf, walk walking the fault lines of Europe about his 1,000-mile hike to follow the path of a wolf across Europe.

00:00:37

Speaker

um Adam, it's nice to finally meet you. Yeah, you too, Ken. Thanks having me on.

The Journey to Alaska

00:00:43

Speaker

Yeah, so way back in 2013, I got an email from a mutual friend up in Alaska saying that you and I, we need the chat. We would have a wonderful conversation.

00:00:55

Speaker

That conversation obviously never happened. um So this is the first time i'm I'm meeting you, talking with you, seeing you. So i guess I guess my first question is, how did you end up in Alaska 10 or so years ago?

00:01:08

Speaker

um via I'd always wanted to go. I think it'd be one of those places, you know, it's it's one of those places that that everyone wants to get to, right? that I met all sorts of Americans from the lower 48 that had Alaska on their bucket list as well. And it was sort of it was sort of similar for me. It was growing up reading Jack London and all that kind of stuff.

00:01:27

Speaker

ah But I ended up going, I got a grant to go to report on um um climate change and and resource extraction essentially. So I spent about four months ah traveling around Alaska, writing stories and that that was what led to Kings the Yukon, one of the stories that that I wrote, ah which was about the decline of the salmon and these 23 Yupik fishermen that had protested it by going out fishing anyway.

00:01:50

Speaker

I wrote an article about that, which then became Kings of the Yukon. But while I was there, I came across the the essay that you'd written about Chris McCandless and the bus.

Inspiration from 'Into the Wild'

00:01:59

Speaker

um And I was spending quite a lot of time in Denali.

00:02:02

Speaker

And we'd actually picked picked up a hitchhiker who was who was going out to the bus, but without a map and without anything. And and in reading your piece and and that hitchhiker kind of inspired an essay about the bus as well. So I was aware of your work from from from then, basically.

00:02:18

Speaker

I'll have to find the essay of yours. I'll put it in the show notes about McCallus. Yeah. Just to briefly touch on Chris McCallus, I titled this podcast out of the wild, the kind of a playful allusion to, to into the wild.

00:02:32

Speaker

ah Yeah. So what are your thoughts on Chris and the bus and his whole journey? He's been called everything from crazy to suicidal to and of a visionary. Yeah.

00:02:44

Speaker

I mean, it was interesting to me because I definitely came to it from that perspective. It was kind of my coming of age as well. I remember watching Into the Wild when I was 21 or something and and having this long argument with my girlfriend at the time about, you know because I sort of, for me, he was this kind of visionary. And then it was going to Alaska ah and and realizing that actually

Influence of Upbringing and Nature Connection

00:03:06

Speaker

many, many people had had kind of long, productive, happy lives out in the bush. But Chris McAndless was the one that kind of became famous sort of through not having the...

00:03:16

Speaker

the was it Was it Nick Janz who wrote... um I think it was Nick Janz, the Alaska photographer, that said that he had the same mentality as the captain of the Exxon Valdez ah of of of basically just not giving enough...

00:03:35

Speaker

I'm struggling to find the word, of of not appreciating the wilderness that he was surrounded by, basically, of just being this kind of man that felt like he could just sort of blast his own kind of vision, whether that was kind of driving an oil tank or whether that was being a hero out in the bush. and there was something about that kind of lack of humility that I started to to see. You know, there were loads of other people that went out and didn't die in the bush and didn't become famous.

00:03:57

Speaker

and And it's strange that this is the one. And then obviously there's all these kids that are now kind of making these pilgrimages out to the bus and then needing to get picked up by helicopters because they can't get back for exactly the same reason that he couldn't get back.

00:04:09

Speaker

ah Yeah, it did bit it but then, you know, it was it was a way in for me. We were all so conflicted about the wild. I think he i think he he speaks to something in that kind of inner city kids who does feel profoundly disconnected from nature. And I and i get it. I get that.

00:04:27

Speaker

that kind of idolization of him as well, because he's done something that so many people that feel disconnected from nature yearn to do, I think. And is that you? is that ah Did you have ah a disconnection from nature? Is that one of the reasons why you were drawn to a place like Alaska?

00:04:45

Speaker

i mean, I was lucky enough to have mum and dad who who who gave me a love of nature, not in a profound way. We never did anything... big and dramatic and long, but we we went and spent a lot of time kind of hiking the coast path in Cornwall. And my dad taught me a lot about the garden and in a very sort of, in quite a small, but quite profound way that they they really passed it on.

00:05:09

Speaker

So I think I was drawn to the bigger experience, but I i think I had a sort of, they they gave me a kind of love and respect from it, I suppose.

Adventures Across Europe and Pilgrimages

00:05:19

Speaker

um And from my from my wife as well, earlier we've been together sort 12, 13 years now. she's She's from right up in the north of of Sweden. She grew up in the Arctic Circle. and And growing up there, you learn this real respect for the natural world. You know, the natural world is really something that can kill you if you make a mistake. You're kind of going out in minus 50 and And I think from her as well, I've i've got this, yeah, this respect, which I guess is in the Into the Wild story, respect is the kind of the bit that seems to have be missing, which I think is unfair on Chris McAndis, right? Because he was 22. And if he was in his forty s or his 50s now, that would have been some awful experience that he learned from and grew from. And he'd probably also have a lot of respect. It's it's kind of unfair to label him as this kid that never grew up, you know, that never learned to respect nature, because I'm sure

00:06:09

Speaker

he would have done and and into the world would have just been a good story that he told in the bar now if he'd if he'd survived it and that he learned from, but he just didn't have the the chance to learn from it. So you have this respect, but you also have this wanderlust and I wonder how long you've had this for it. Could you give us like a quick rundown of your major expeditions? Cause you've been across Europe to Istanbul, you've been across Scotland. Yeah. What what are your your main expeditions there?

00:06:38

Speaker

Yeah, it sort of snowballed, you know. i had had a friend at university, ah gareth um Gareth Walker, ironically, um and and he walked the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in northwest Spain.

00:06:54

Speaker

um and And just his stories made me want to do it. So the next summer I walked

Traveling by Canoe and Local Perspectives

00:07:00

Speaker

it as well. It was ah it was a month from the from the Pyrenees to, think I said northeast, the the northwest coast of Spain.

00:07:07

Speaker

um And I loved it. And it and it really it really stuck in some way that, I don't know, i I guess I found it quite hard to put my finger on, but I became very interested, particularly in pilgrimage and and that requirement to kind of go out on a long walk, but not so much for the destination. I wasn't Catholic. The kind of arrival in Santiago didn't mean a huge amount to me, but there was something about the journey that I that i loved. And so a couple years after that,

00:07:35

Speaker

um I walked from England to Istanbul, which was the better part of a year. Again, i ah the actual intention was to go to Jerusalem because I was, again, wanted to kind of frame it around this idea of pilgrimage.

00:07:47

Speaker

um And for various reasons, I ended up having to to to stop in Istanbul. ah But there was something about that journey, about being, traveling long distance and the sort of string of connection that is that it opened up that I would...

00:08:04

Speaker

meet someone and they would say, oh, well, you're going that way. You have to go and stay with my cousin who's 20 miles down the road. And they would tell me about this really nice mountain hut that they knew about. And then I get to the mountain hut and there'd be someone there. And then I'd walk with them for two days. It was just this completely unplanned way of of crossing the continent, you know?

00:08:22

Speaker

ah And when I was thinking about my first book, Kings of the Yukon, which like you said, is this 2000 mile canoe trip across Canada and Alaska following the journey of the King Salmon.

00:08:34

Speaker

and Not only is it kind of the only way to travel across across Alaska, you look at a map of Alaska and the Yukon is the... The highway really is the main way to get across. But there was something about researching in that way.

00:08:46

Speaker

ah the The first time I've been in Alaska in 2013, I'd been there more as a journalist and I'd get a little a bush plane and I'd fly into some Yupik or Athabascan village and try and speak to people. And I found it incredibly difficult and challenging to to kind of bridge that divide.

00:09:02

Speaker

just to go and knock on people's doors and kind of start conversations. People were quite distrustful and I

Impact of Journeys on Life Perspective

00:09:07

Speaker

was quite, quite nervous, but there was something about being in the canoe that I felt people both, both appreciated that I was taking my time and kind of connecting to their river and their landscape.

00:09:18

Speaker

And again, it opened up that string of connection. So I would meet just the most diverse cross section of people that I could never have planned. and And again, people would say, oh, well, you know, my brother's fishing,

00:09:30

Speaker

downstream at Ruby, you know, you you have to go see my brother when you get to Ruby and then then Ruby, the the brother would want to know all the gossip about what was happening up with it. So we had this kind of reason for being there.

00:09:40

Speaker

um And this, yeah, it just felt like a much more interesting in-depth way to research. So it kind of humanizes you in the eyes of of others. It kind of brings brings you down to ah other people's level.

00:09:54

Speaker

How do you this is something I grapple with because I've been on a few journeys myself. I like myself better when I'm on journey. I'm wondering if you have something similar. I feel like I'm more open to experience. I'm less grumpy. I'm obviously in in fitter shape. what is it What is it like for you?

00:10:15

Speaker

Or at least if you're, if you are grumpy, you don't have anyone else to take it out on, right? You only have yourself. And sometimes if you don't absorb your own grumpiness yeah if you don't have anybody to degree be grumpy with, you're just not grumpy.

00:10:28

Speaker

i'm um I'm awful when I'm hungry at home, but when I'm walking, it's like I can deal with it. um Yeah, I agree. i agree. It, it, it puts me in a place that feels fairly unique.

00:10:42

Speaker

Um, and yeah i've I've just come back from a festival this weekend. I've been at a festival with my wife for four days and and it's a similar space that kind of slightly liminal outside of real life, a different way of interacting.

00:10:56

Speaker

um I guess there's a lack of, not a lack of responsibility and obviously you're there, you know, working and, and, and, and and travel. It's that kind of single-minded focus on something.

00:11:09

Speaker

It's been interesting becoming a dad. Uh, I've got two kids now who are seven and four. Um, and it's been interesting doing this last book and feeling that kind of dual pull because, um,

00:11:22

Speaker

on previous trips I've just been so immersed and there's just nowhere else that I want to be apart from on this trip. and And now with this, with this last book, Lone Wolf, I've, you know, the kids have been at home and I've done the book in sort of two or three weeks since then gone back to be with them.

00:11:37

Speaker

And I feel in some ways in sort of in two different places, you know, that it's, you don't kind of fully immerse yourself in that journey because it's just a big part of me that that's missing them and and wanting to share what I'm doing with them.

00:11:50

Speaker

um So we are starting to think maybe about doing a trip as a family because it feels like that way of being able to have that kind of single-minded immersion again.

00:12:02

Speaker

I see.

Decision Against Settling in Alaska or Sweden

00:12:03

Speaker

i'm going to move on to Lone Wolf soon, but just to stick with Alaska for just one more thought here, because you sprinkle Alaska throughout the book Lone Wolf and you do so in this kind of bittersweet way, which is very familiar to me because, you know, I spent...

00:12:20

Speaker

um seven years off and on up in Alaska. And Alaska just gave me something that no place ever did, which is you know that brush with wilderness, that wild delight, a little bit of delightful fear, the exuberance, the freedom, the moments of sublime, which I just don't get from my village in Scotland, unfortunately. So I'm sure at some point you it floated through your mind, oh, maybe I could get a cabin and stay in Alaska, or or I didn't know your wife came from you know Arctic Sweden. I'm sure that was a conversation. Why why not find a cabin up in Sweden? So I guess, why didn't you stay or why didn't you try to find a life like that, that where you could have kind of held on to those things a bit better?

00:13:06

Speaker

Family and friends, really, I think. I can really see that in another life I i stayed in Alaska um for for all the reasons that you just said and and also for for people as well. I think i so I spent a long time in Fairbanks and I just i just loved the people there and the attitudes and the the the yeah ah that that way of being in that place. i i I completely fell in love with the place. um And yeah, I do question why I left sometimes. But then I there was there was i i met early just after coming back from Alaska on ah um on that first long trip.

00:13:44

Speaker

And... it It was interesting to me that i'd I'd met someone from a very similar environment. There was a kind of, well, actually, maybe you can have this, you know, and we do go back to her hometown quite a lot. Her sister's still up there and they have a summer house on the river and it is, you know, it's it's not quite Alaska, but there are there are big mountains and and and big animals and ah the mentality is quite different. The Swedish mentality is very different to an Alaska mentality, but it it definitely scratches some of that itch.

00:14:13

Speaker

Yeah. um So let's let's get on to to Lone Wolf here, which is just a terrific

Tracing a Wolf Across Europe

00:14:20

Speaker

book. I finished it last night. So you track this wolf a thousand miles across Europe. And, you know, there's some people who actually like live with wolves, you know, they raise them from pups and they probably learn a ton about wolf behavior from living with the wolf.

00:14:38

Speaker

But what, what do you learn from tracking a wolf following its long migratory route that maybe they don't learn?

00:14:51

Speaker

Yeah, I mean, I think i was I was definitely the first person to track this particular wolf. that This wolf had been well studied. ah Stouts was born in the south of Slovenia and had this tracking collar put on him, did this thousand mile walk ah across Slovenia, across Austria, came into Italy.

00:15:11

Speaker

um And he'd been well studied. There'd lot of papers about him, but no one had actually followed him in this way. And it was really interesting to me to sort of try and breathe that life back into the into the data.

00:15:24

Speaker

um Even from so starting to transfer those data points onto the maps that I had, there would be these moments when he would seem that he would change direction for no apparent reason or or make decisions that that that felt impossible to understand. But when I actually started walking it, you'd realize, oh, well, when I got to this top of the hill,

00:15:46

Speaker

I was able to to hear the airport and or, you know, and then suddenly he would he would change tack and take off on another bearing or you'd get to a mountain pass that was particularly inaccessible, um particularly in the winter when he'd done it when it was very heavy snow year.

00:16:02

Speaker

So in however kind of clumsy a way, you I felt like I started to to to get behind the sense of how he was making decisions of how he was navigating the landscape and and often kind of following the easiest path as well. If there was a if there was a bike path along the river, then then he would he would take that over kind of going through you know along along the side of the mountain.

00:16:25

Speaker

So yeah, there there was a sense, however imperfect, of of of starting to to see the world through the eyes of a wolf in a way that you couldn't from just just trying to interpret it all off of a computer.

00:16:38

Speaker

It's such a novel idea for an expedition, for a travel book to kind of find like a migratory route not the best way, but you know, just this path that this wild wolf took and I can think of maybe a couple other books, I think, Becoming Caribou. They kind of talk about following caribou, but there's not a lot of books like this. What was it like the moment when you thought, oh, I could actually hike this. Maybe I could get a book out. It must have been a pretty special moment.

00:17:09

Speaker

Yeah, the the the moment it became real was when Hubert, who is the biologist who from the University of Ljubljana, who first put the tracking collar onto Schlauze, of course, with no idea then what what he would go on to do. The idea was just to be sort of seeing how wolves behaved within their territory.

00:17:28

Speaker

Yeah. But Hubert knew the den where he was born. And in the winter, before I set off on the journey, Hubert took me to the to the den, which was up on this mountain called Slavnik Mountain in the south of Slovenia.

00:17:41

Speaker

It's this is kind of limestone plateau with all these holes, the way that limestone mountains have these kind of holes gouged out by water. And and Hubert took me to Slavnik's den and I crawled down into the den, which was kind of about a few meters below the surface of the of the hillside.

00:17:59

Speaker

And being in there and then knowing exactly where Schlauts was now on the other side of the of the sea in and northeast Italy was incredibly intimate.

00:18:10

Speaker

I really felt like I'd never been closer to a wild animal. um And I got a sense of that buzz that people like Hubert must get as ah working as a wildlife biologist, getting to know not just how wolves live, but getting to know the lives of individual wolves and and their family structures and what makes them tick.

00:18:32

Speaker

it almost kind of getting to step across that threshold in in a way and and and get a glimpse of how another species understands the world. So that was the moment when I think it turned from being this sort of abstract idea into into something very, very real that I was doing.

00:18:48

Speaker

the the other The other sort of seed that had really made me interested in Schlotz's journey was having read. So so where he arrived ah is a place called Licinia, which is this regional park in the quite low mountains, about a thousand meters just north of Verona.

00:19:08

Speaker

um And it's the same place that a lot of refugees are being settled at the moment. um Refugees who often arrive on Lampedusa coming from North Africa, and then they get taken directly to these mountains. there' an old NATO barracks there, and they're being settled in these barracks in the middle of nowhere.

00:19:26

Speaker

and a lot i And I read this small news article in the local Italian press about it and a lot of the language that was being used by local people about the arrival of the wolf and about the arrival of the refugee was very similar. it was, you know, we were here first.

00:19:40

Speaker

I don't have a problem with the wolf, the refugee, but their place isn't here. And so that as well made it feel like there was something really interesting going on here in these two separate journeys to get to this place that I'd never heard of. um and And the reception, that the the change that was happening in this place really really drew me in as well.

Cultural Views on Wolves in Europe vs. North America

00:20:02

Speaker

Gotcha. So you and i we both have a connection to to Alaska and and to Europe, and wolves are perceived very differently each area. continent. And I think in North America, even though we almost got rid of the wolf, we have a slightly more benign view of the wolf. And that's partly because there's so very few recorded killings, like it's gotta be like less than half a dozen or something.

00:20:26

Speaker

Whereas in Europe, there is a long history of, you know, very bad wolf human relations. At one point in your book, you cite a statistic from an expert who says there may have been as many as um over 5,000 victims between the 16th and 20th centuries just in France.

00:20:46

Speaker

Now, having done this research, what is your, how do you get a sense of the difference there? Like, why are there so few wolf killings of humans in North America versus in Europe?

00:20:59

Speaker

I think a lot of it comes down to shepherding. um Obviously, Europe is a much more densely populated continent than than than Alaska or the northern part of Canada.

00:21:11

Speaker

um And the typical way of shepherding kind of through the Middle Ages was to send out young boys but you know, 10 years old or so to be to be with the flock, often right on the edge of the forest. Already the forests were being cleared, so the the populations of wolves were being condensed, the forests were being cleared to make way for livestock.

00:21:35

Speaker

So the wolf was... losing its prey species, the the the deer were getting pushed back as the forests were getting pushed back. so and And so you'd have these young boys with a lot of prey right on the edge of a forest.

00:21:50

Speaker

ah and And wolves are are opportunists, you know. so um But I think is it yeah and it's hard to extrapolate. You know, we ah we live in an extremely different way now. The wolf hasn't changed, but we have fundamentally changed in how we live and interact with the landscape in the last 500 years.

00:22:08

Speaker

um And, you know, were the wolf to come back now as a and and and as it is beginning to come back, the chances of seeing them now are very small simply because we're just not out there living on the land in in in in the ways that we used to.

Wolves in Pop Culture and Mythology

00:22:24

Speaker

And our um relationship with the wolf is based on a few things, kind of this long entrenched history, maybe history, personal interactions, you know, of a wolf coming through our our town and taking a sheep or whatever, or just being this beautiful animal that we saw and pop culture, like how the wolf is represented in pop culture. You know, I was one of my daughter's favorite movie is frozen. That's basically every little girl's favorite movie.

00:22:53

Speaker

I got so pissed off at frozen when I watched it. That's a 2013 movie. And at one point early in the movie, you get this pack of wolves chasing, um i think a sled with Sven the reindeer.

00:23:08

Speaker

And I'm just like, come on guys. This is, it's 2013. No, I read a Barry Lopez book of wolves and men that came out in 1978. And Barry Lopez talks about how wolves have been unfairly portrayed in pop culture and this is why we're so afraid and angry and hateful of wolves so i got so upset at disney come on it's like 2013 we should know to represent them better and now there's movies like um wolf walkers i don't know if you saw that kind of an irish movie did you do like a survey of of

00:23:45

Speaker

wolf representation in pop culture at all for this this book? I watched quite a lot werewolf films. um At some point I kind of felt like I had to draw a line. ah and that you know my my My previous book was about salmon and when I first went to the library and you know started taking out the books about salmon, it was it was a fairly limited set. when When you go to the British library and type wolf into the catalogue, it is absolutely overwhelming.

00:24:12

Speaker

And so There were some seeds of pop culture that led me in. I've always loved Angela Carter's work. She wrote a collection called The Bloody Chamber, which is a kind of retelling of of wolf stories. Cormac McCarthy's The Crossing, which the first kind of hundred pages of that is this beautiful...

00:24:28

Speaker

narrative of about about a young man and a wolf. um So i had I had ways in in and and I do delve into the into the fairy tales quite a lot in the book.

00:24:39

Speaker

um In terms of that sort of misrepresentation, one of the... things which i I kind of hit upon was this sense, and maybe this is a reason, I i don't know what it's how how rabies kind of plays out in in Alaska and Canada, but some of the stories of rabid wolves that I read, accurate kind of historical stories about rabid wolves, which were absolutely horrific. you know like As I said, what wolves are very shy, that that that they will stay away from people, there are

00:25:09

Speaker

few recorded instances in in in the last century or two of of of people being killed by wolves. But rabbit attacks are are absolutely horrific. you know that the that A wolf will be completely fearless, will come into a village, will bite many, many people.

00:25:25

Speaker

Many of them will die. Many of the others will die from babies later. and like You could really see how a single incident like that, particularly in in a kind of oral culture,

00:25:37

Speaker

would be passed down over the generations and you wouldn't really need to even embellish it. um And i could I could really understand how how certain incidents like that would really prey on the collective mind ah that down the years.

00:25:51

Speaker

And i do I do wonder if that's where a lot of this kind of misportrayal came from. and Are you comfortable calling it a misportrayal?

00:26:01

Speaker

Because, like you know, as you point out, like thousands of people have have died in Europe because of wolves and untold amount of cows and sheep. I guess just how legitimate is this kind of entrenched fear and hatred?

00:26:18

Speaker

I think the misportrayal is the sense that the wolf is a willful, calculating, evil animal.

00:26:29

Speaker

that That seems to be... but when when you When you look at the ways that they have been killed, there is something to me that feels like it goes beyond protecting one's own life and one's own flock and and verges on...

00:26:45

Speaker

hatred and revenge. and And North America was kind of the pinnacle of that. You know, wolves were, again, kind of going back to Barry Lopez's book, and and he documents the the myriad ways in which wolves were set on fire and torn apart by horses and then paraded on horseback through towns like bandits that had been captured.

00:27:06

Speaker

um Ted Williams writes that amongst native people, that were they that they they saw what the settlers were doing. They thought it was a kind of manifestation of insanity, the the the number of wolves that were slaughtered.

00:27:19

Speaker

it's It's been a very quick leap. you know as soon as As soon as Jesus has been the lamb, that the the wolf has then been been played the role of the devil. And and that that failure to be able to see the wolf as a wolf, not to be able to put the story, to be always putting a

Farmers' Challenges and Coexistence with Wolves

00:27:37

Speaker

story onto it. That that I think is the misbetrayal.

00:27:39

Speaker

I also think it's a misbetrayal and you do hear this a lot in kind of wolf circles as well, which is that a wolf would never kill someone. A wolf would never harm a person. A wolf would never harm a dog. And and that that is another myth. you know that That is a myth that now certain proponents of rewilding seem that they feel like they need to put about in order for us to accept wolves back. And I think that is equally dangerous to try and make the wolf now fu fulfill some other story that we like to have about the world. Not now that the wolf is going to destroy us, but the wolf is going to save us. And and that's that's equally false.

00:28:14

Speaker

So as there was some of this outrage back then, but there's some of this outrage right now. At one point in your book, you write, I'm still finding it hard to comprehend the sheer outrage that the Wolf's return provokes.

00:28:30

Speaker

what What's your best explanation of why this outrage is so strong? I feel like it's being inflamed for political gain, really.

00:28:41

Speaker

Um, The main reason, yeah, I think you could say the main reason that the wolf is doing well in Europe as of the last three decades or so is that it's been protected by the European Union.

00:28:54

Speaker

And so it's a very short distance from having a problem with the wolf to having a problem with the European Union. And I really understand. And I met a lot of farmers on this trip who do not like having the wolf back. And I really understand that, you know, farmers are living incredibly hard lives at the moment. And that's not just because of the wolf.

00:29:14

Speaker

The year that I did the walk, it was the driest summer in Europe in 500 years. i Russia invading Ukraine had led to huge spikes in the cost of animal feed and energy.

00:29:26

Speaker

Young people don't want to farm anymore. they're They're leaving the family farms and they're moving to the cities. And now farmers are being asked to accept these large carnivores back into their midst as well. Like, I get it. um But there are proven ways to coexist with wolves. There needs to be a certain acceptance that wolves have returned to the continent now. That's not going to that's not going to change. We're not going to eradicate them all anymore.

00:29:50

Speaker

and is is that it's not that I don't understand the farmer's anger, but I would see politicians saying to farmers, don't protect your flocks, but instead almost allow the disaster to happen in the same way that you see with populist politicians in the UK, create the disaster to then be able to go to the European Union and say something has to change or we have to pull out of Europe because that's the only way for us to protect our own.

00:30:16

Speaker

So it was that way of seeing politicians inflaming the anger in the countryside rather than offering positive solutions, as we've seen with all of the farmers' protests that are happening across Europe and North America.

00:30:29

Speaker

Farmers are protesting for very legitimate concerns, but rather than politicians addressing those concerns, they're inflaming those concerns in order to get that royal vote, particularly on the far right. and And that to me is is really where that that outrage is is being kind of tended and nursed and flamed now.

00:30:49

Speaker

Interesting. um As I started the book, um I found myself having this kind of this knee-jerk dismissiveness towards the farmers and and ranchers. um I think there is, i think George Monbiot talks about this a little little bit in his book,

00:31:09

Speaker

Feral, which is about rewilding Britain, about how sometimes we almost give too much too much of a voice to farmers who you know represent 1% to 2% of the country. There's actually a lot of farming that does a lot of damage to the land and waters and ecology.

00:31:27

Speaker

Maybe it's time for other 98% to have proportional voice. you know a proportional voice But as the book went on, I started to have a great deal of compassion for for these folks.

00:31:40

Speaker

But I'm wondering if you, like me, kind of carried some of that dismissiveness or bias against some of these folks who have a kind of a very anthropocentric or me-centric worldview to the point where they can't even entertain the idea of wolves or kind of a more eco-centric perspective?

00:32:05

Speaker

um I think not by the time I came to write this book. I definitely have in the past, but I've seen a lot of the damage that has been done like from that attitude of of of this is only one or two percent. you know is Particularly in Wales, a lot of rewilding projects have ended essentially in disaster because people have failed to engage the farmers. People have turned up from the cities with their books and their ideas and said, this is how we're going to do it.

00:32:33

Speaker

and And you see you know placards and fields all over Wales is now that say yes to nature, no to rewilding. you know what And i did a walk across Scotland a few years previous to this, again talking to people about how they'd feel about the idea of wolves coming back there. And what I what i saw that farmers here in the world rewilding is really a continuation of the clearances.

00:32:56

Speaker

It's the sense that we're just, whoever's on the land is a kind of impediment to our vision of this sort of Garden of Eden place that we'd like to return to. And what the clearances began, moving most people off of the land, rewilding is kind of aiming to to finish.

00:33:13

Speaker

um And that's, of course, not to excuse all farming. A lot of farming is is hugely detrimental. and and yeah And it's an ongoing question about whether any livestock farming can be. I don't ah really don't know where I want to come down on the whole regenerative agriculture. ah i'm just I'm not an expert there at all.

00:33:31

Speaker

But what I did see in these traditional ways of farming in the Alps, people that are still practicing the transhumance, people that are still kind of walking up into the Alps of the summer, coming down in winter, making beautiful organic cheeses, living these kind of vibrant pastoral cultures. that there's there's a There's a profound, you know, we we we say we're in a biodiversity crisis, but also in a huge cultural diversity crisis. we use it We're losing so many different ways of living with the world and and and being and and thinking about the world and being part of the world. And

00:34:04

Speaker

When I saw the profound relationships that people had with their sheepdogs and their animals and their ways of living on the land and their ways of understanding the land, I don't know if I want to get rid of all of that just for you know just for an idea of, ah well, this is how I think it should be. We need to go back to some kind of former ecosystem idea. Yeah.

00:34:28

Speaker

And I think it's also a dangerous idea. And we've seen this with, you know, what's happening with farmers protests in the yeah UK at the moment. Farming might be sort of 1% or 2% of the population, but they really carry the sense of a country's soul and a country's culture.

00:34:42

Speaker

You know, the the the farmers protests have blown up hugely. They've become this huge divisive point against against what Labour have done previously. um and and we've seen that all over Europe and North America as well and and so to to ignore farmers is is a very dangerous position as well and the and the far right absolutely know that the far right absolutely know that they are the people at the moment that are trying to appeal to the farmers because the farmers represent this idea of yeah of of of the soul of a country in a way I think

00:35:14

Speaker

As I said by the the time I got to the end of the book especially when this one couple was talking about this deer, don't know if it was a dairy cow they had that had just been like ripped to shreds by some wolves. I was, I felt so bad for them. And i really congratulate you for such a compassionate and universal approach you took to this book. I wasn't expecting to get that by the end of Lone Wolf, but I really did.

00:35:47

Speaker

What is to be... done? what is What can some upland sheep herder or someone who's raising cattle, what can they do to protect their flock flock rather than just taking those 5,000 euros from the government every time a wolf takes one of their animals?

00:36:09

Speaker

Which is inadequate as well. You know, the the the compensation that is offered by the EU. I would meet people, I'd met one horse breeder in Slovenia who had lost his best breeding mare to a bear, actually not to a wolf, but to a bear.

00:36:25

Speaker

And he was saying to me, you know, there's no way that any sort of monetary compensation can can make up for this mare, which has been selected over generations for to to to maximize the the genetics that he was after.

00:36:39

Speaker

So it has to be thinking about coexistence in some way. And there are there are ways to do it. you can You can put electric fences around your flock at night. um You can live with these huge...

00:36:52

Speaker

ah but various different types of guardian dog that can live with the flock and kind of think they are part of the flock and will and will defend the flock against wolves. It all requires a lot more effort. It really does. you the these These herders have got very used to sending their flocks up into the mountains for the summer and then just coming up and rounding them up in the autumn and bringing them back down.

00:37:15

Speaker

You can't do that anymore. You need to be up there every day, checking on them, putting them inside fences at night. So it's possible, but it what wolves mean is is a lot more work. um and People would say to me you know that that there are various things that don't don't work inside that, particularly in the height of summer the flocks like to be grazing at night because it's too hot to be out during the day so it it requires a lot of readjustment in the way that things have been traditionally done I did meet the occasional shepherd and farmer who wasn't anti-wolf I'd hesitate hesitate to say pro-wolf but not but not anti-wolf and who did understand

00:37:56

Speaker

the reason and and the need for them to be there and and would be kind of slightly thrilled about having them having them back as well. I met a lot of shepherds who absolutely hated wolves, but were quite pro wolf in the sense of, if I believe in reincarnation, if I was to come back as an animal, I'd really like to come back as a wolf, you know, that they see them as the see themselves as the kind of top dog and and and the alpha fighter.

00:38:19

Speaker

So they're kind of romanticized in that way. But Yeah, I think there is a way of there is a way of living alongside them again. But you know even to say that is it' it's still just kind of someone from the city kind of telling people how they should live. you know It has to come.

00:38:38

Speaker

And what I found most inspiring was it was farmers who were trying to work with their colleagues, people that live people that live in the same neighborhood who are saying, this you know this is what we're doing. We are making it work. This is what you could do as well.

00:38:54

Speaker

So you do think there's adaptations that can be made to coexist? They have to be made. you knowre We're not going to wipe out wolves again unless the the the status of the wolf has just been downgraded in Europe now now from from strictly protected to protected. and So they've become a little bit easier to shoot. we We can discuss the kind of pros and cons of that, but it's not a completely bad thing that that farmers now have a bit more agency to protect their flocks.

00:39:24

Speaker

but short of going back to the kind of 19th century all-out genocide. Yeah. And and there's even there's even work that's been done that shows that when you shoot a wolf, it actually makes the problem worse in the same way that people have more kids during wars ah and unless you're kind of...

00:39:43

Speaker

wiping out a population to a critical level, it can actually seem to make the problem worse. and Wolves that lose the dominant members of their pack actually seem to attack more sheep because they become disorientated, not less. so We're not going to wipe them out. We're not going to get rid of them again. Wolves are wolves are back in Europe to stay.

00:39:59

Speaker

and so We have to learn how to live with them. There is no

Rewilding and Living with Wildlife

00:40:03

Speaker

other way. Again, and again um i yeah that that yeah yeah and Maybe I'll stop there, but I was going to go off on another idea. But yes, that there there is no it's it's not an option. to to we We need to learn how to coexist. And there are great, great groups working with farmers, helping them to to learn how to do that.

00:40:28

Speaker

And I'm sure there's folks kind deep in the weeds on these issues and kind of like exact what's allowed, what's not allowed, without knowing much about it um I imagine the scenario of a wolf is attacking ah cow or a sheep and there being some controversy about, are you allowed to protect that by killing the wolf?

00:40:50

Speaker

where Where do you stand on, on some of these issues? Is is that an acceptable response in your view?

00:41:00

Speaker

Again, it's, I don't know if I'm the person to sort of make that moral judgment there. and I think the wolf has suffered from, in some ways, those who campaign for the wolf seeing life being so sacred that no wolf may ever be harmed, but particularly particularly in Italy where there is now a problem with hybridizing. So where wolves are...

00:41:30

Speaker

having offspring with feral dogs, which is which is not great for the kind of ongoing, it's sort of the same as the wildcat in Scotland, which is the ah which is really suffering now from having offspring with feral cats and there's very few true wildcats left.

00:41:47

Speaker

And there's a concern that wolves are going to hybridize with dogs more and more and and lose that pure genetic strain. um But it's impossible in Italy or has been up until recently to shoot a half dog, half wolf because they are so well protected. And so the only way at huge expense is to capture them and sterilize them.

00:42:06

Speaker

um But obviously that's impossible to, you know, so hard to catch wolf to see a wolf the that really protecting them to that degree only creates a bigger problem. And, you know, and I would meet a lot of farmers that could not understand.

00:42:21

Speaker

you You can get a derogation at the moment to shoot what's called a problem wolf, but it takes many weeks to come through. you only then have a certain time to shoot that wolf. It's very hard to shoot a wolf.

00:42:35

Speaker

And I would meet farmers that could not understand when their great grandfathers were allowed to go and, you know, just kill a wolf that was harming their flock, that they had to go through this massive process and engage with local government and wait to get a permit back and then only have four weeks to be able to do it. Mm-hmm.

00:42:49

Speaker

That's what makes people angry. it's not It's not so much that a wolf has killed a sheep, but it's it's the it's the sense of being controlled by by someone else from somewhere else, I think, that that makes people angry. in it and and that Within that space is where the kind of conspiracies start to thrive and and the anger starts to thrive and and and people look for these kind of radical political solutions and stuff.

00:43:15

Speaker

So that said i i do it's I worry that you know this is the kind of beginning of setting something in motion where it becomes easier to shoot other large carnivores.

00:43:31

Speaker

the The wolf is, despite being of least concern across the continent as a species, there are certain places like in Scandinavia where the wolf still is really struggling um and they do need strong local protection, which they're not going to get if if it's downgraded in this way.

00:43:47

Speaker

So yeah, it's it's a balance. um Luigi Bottani, who's is the one of the leading Italian wolf experts, said something like, if we can ah you know if we if we can trust people to be rational, then this downgrading of the wolf status is not a problem.

00:44:01

Speaker

ah But really the main thing that I saw in my walk across Europe is that when people relate to the wolf, they do not relate in rational ways, what one way or the other, for for love or for hate. And so so, yeah, it kind of remains to be seen how it's going to how it's going to impact on them.

00:44:18

Speaker

You have a ah brief aside about um bears in your book, and you talk about bears that had attacked humans and that were... executed.

00:44:30

Speaker

um and you say, certainly we should manage the risks as best we can. But rewilding means that the wild gets a hand back in the game with an agency all of its own.

00:44:45

Speaker

um I'm interested if you'd like to elaborate on that, because one reading of that line may be suggesting that bears who attack humans can kind of live without fear of of human justice.

00:45:01

Speaker

um So yeah, I'm just getting wondering where you sit on that. No, I think absolutely. um so so So the bear in question who killed a 26-year-old fell runner, Andrea Papi, two years ago now, was a bear that had previously attacked several other people.

00:45:26

Speaker

and the bear had not been killed because of protests by environmental groups. And i feel in quite a direct way, the failure to deal with that bear um led to Andrea Pappi's death. i you know We know, and we've we've both been in Alaska, we like you you know there are certain bears that have these reputations, that have maybe come to associate people with food or whatever it is, and and there is no way to manage these bears apart from to kill them.

00:45:56

Speaker

I think it was almost the opposite. It was this failure to to deal with that bear. Had it been a pet dog that had already attacked four people, there's no way that it would have been allowed to to continue its life, right? that that like we We put down animals like that because we understand that it's not possible to to live safely alongside them.

00:46:16

Speaker

But at the same time, and again, from you know we've spent time in Alaska, ah a few people are killed by bears in Alaska, and there is not a sudden cry to exterminate all bears in Alaska every time it happens.

00:46:32

Speaker

um And it's that sense that, you know, I think what's interesting about the wolf, and we talk a but lot about bringing with the wolf back to the UK, which we are a long way from from happening,

00:46:48

Speaker

But i think the reason that the wolf is an interesting species species to talk about in terms of rewilding is it is provocative and it asks us those questions. You know, we we like to say that we want to rewild and we like to say that we want to live closer to nature and we want to live alongside nature.

00:47:04

Speaker

But that is not always necessarily a comfortable and cozy experience that that demands di us to act in nature in in different ways. as Again, ah ki going back to Alaska, but as you know, when you travel in Alaska, you camp in a different way. you You cook in a different way. You think about where you go in a different way.

00:47:25

Speaker

i in and in compared to how you live in in Scotland or England or or wherever. And it's it's not it's not as, yeah, it it it requires something of us. And I think that switching that relationship to how we think about the world, I think is really important, but it's not all safe

Conclusion and Podcast Subscription Info

00:47:46

Speaker

and gozy.

00:47:46

Speaker

Mm-hmm.

00:47:50

Speaker

Yeah, I lived in Lake Clark National Park for a summer. So I was living on a coast and I was basically surrounded by bears. I had 100 grizzly bears on this coast. I'd see probably 30 bears every single day. And towards the end of summer, i so like, I couldn't live like this. It's just too much fear. It's just too much cortisol drip dripping into my bloodstream every day. And the truth is,

00:48:16

Speaker

The Native Americans in Alaska didn't live that way either. They didn't let 30 grizzly bears live inside the town with them. And, you know, I've up in the Arctic, Aniktuvik Pass, they're pretty, the the Inuit people up there, they're like, you better take a gun when you go out.

00:48:34

Speaker

And they often talk about shooting bears. And I'm sure they have, you know, their own ecocentric view of things, but that ecocentric view might also involve bears don't get to live anywhere near town as well.

00:48:51

Speaker

So, yeah, I think, I think there is this dreamy view of rewilding where we're all kind of be, you know holding hands with, with bears, but it's, it's not, it doesn't work out that way. Exactly. And you, took you yeah you have this wonderful quote from Bruce Chapman, a travel writer. What did he do?

00:49:10

Speaker

in Patagonia and songlines. There's two of his classics. And he says that we're a species on holiday. And he's basically talking about how we got rid of all of the dangers and carnivores.

00:49:24

Speaker

And, you know, we're not, we're at the top of the food chain. Hey folks, thanks for listening. There's still 20, 30 minutes left in this podcast available to paid subscribers. If you'd like to become a paid subscriber, go to my Substack page, Out of the Wild with Ken Ilgunis, and you'll have access to all my essays, movie lists, movie reviews, all that stuff.

00:49:48

Speaker

Thanks again for listening.

00:50:04

Speaker

This is the Out of the Wild podcast with Ken Ilgunis. Original music by Duncan Barrett.