Become a Creator today!Start creating today - Share your story with the world!

Start for free

00:00:00

00:00:01

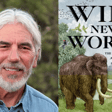

#4 Seth Kantner on sod igloos, slow writing, and arctic racism

Seth Kantner is an Alaskan photographer, hunter, fisherman and author. He’s written two of my favorite books: Ordinary Wolves, a fictional book about a boy growing up with the ways of his indigenous neighbors; and his latest book, A Thousand Trails Home, about Alaskan caribou and our relationship with them. Topics include…

Upgrade to paid

- Ken thinks that couples in arctic cabins should be highly qualified to write marriage advice books. Seth splashes cold water on that idea, saying all they’re doing is avoiding conflict.

- Knitting, the first videogame?

- The drawbacks (face-blindness) of being homeschooled in a sod igloo.

- Middle school, is there a point?

- Kim Kardashian vs Seth Kantner. In the fight for cultural dominance, sadly Kim wins.

- The merits/necessity of slow writing.

- How it’s good to have a phobia of wasting somebody’s time.

- Plus, the fascinating topic of race relations in arctic Alaska.

Transcript

Introduction to Seth Kantner's Life and Works

00:00:05

Speaker

This is the Out of the Wild podcast with Ken Ilgunis.

00:00:19

Speaker

Seth Kantner is an Alaskan photographer, hunter, fisherman, and author. He's written two of my favorite books, Ordinary Wolves, a fictional book about a boy growing up with the ways of his indigenous neighbors, and his latest book, A Thousand Trails Home, a book about Alaskan caribou and our relationship with them. Seth, hello.

Life in a Sod Igloo and Family Challenges

00:00:39

Speaker

Hello so seth you grew up in a sod igloo in the middle of ah wilderness in alaska i'm wondering if we can start by you bringing me and the listener inside of that sod igloo with you what does it look like what is it smell like.

00:00:57

Speaker

Well, it changed over the years. um My parents um ah went north in the mid-60s there, and it was late ah fall, September, and freezing up, so to speak. And um so they i built fires and heated ah rocks in the fire and then would put that on the permafrost that they were scraping back to dig this hole to make a 14 by 14 hovel. And they had the tunnel entrance. So those your early years, it was dirt floor and um caribou hides first leaping on and stove kind of in the middle. um And then the tunnel, which seemed like a good idea, but actually the wind blew

00:01:46

Speaker

so strong and so consistently that it kind of sucked the orem air out. But my dad would always joke about if you put your cup of coffee on the floor, it'd freeze. But if you stood up, you'd be just sweltering up there. My dad would crawl out and um disappear with the dogs hunting and and crawl back in with meat and and armloads of wood and or stuffing wood in front of him, I guess, in the tunnel there. And pretty quick, um probably by the time I was four or five or six or somewhere in there, it's hard to remember. um

00:02:19

Speaker

They filled they dug out more of the hill added on to the place so it was twice as big and then made a door of sorts that was.

00:02:31

Speaker

cable hides and spruce poles and not quite all American door, but a door, not a tunnel. um And then they filled in the tunnel. And we had none of the normal things like electric lights or running water or ah radio or neighbors.

00:02:51

Speaker

or structures out on the land that you could say like, oh, we'll stop in and visit or shop or or find shelter in a ah building or something. It's just none of that. So life was divided between inside and outside, and outside was, um I would argue, much bigger than many people's outside world. Everything was outside.

00:03:14

Speaker

um And then inside, our world was pretty ah small. We had kerosene lamps, or one wick lamp. Every day was decided by the season and the weather and and necessities. and And none of my family members woke up and said, okay, now I'm leaving the family to go to school or work or something. so were a tight family and then fiercely attached to this one spot on the planet, this one hill along the

Parental Influence and Project Chariot's Impact

00:03:43

Speaker

river. Maybe you can kind of speak for your parents here because I'm wondering what your parents were thinking when they, you know,

00:03:50

Speaker

Started a family um up in this part of Alaska because I've always had like the Alaskan cabin cabin fantasy too and there's probably a few reasons why that just never happened for me but I think one of them was you know if I start a family I probably want my child to have a broader community and schools and interacting with people and Education kind of promoting those social skills was this um like a something that your parents consider that's interesting you say that so my parents were um you know still are but white people from ohio um and they didn't know each other there and and my dad was raised to

00:04:28

Speaker

in Catholic school, I guess. And I think when he turned 17, he just wanted to get as far from the city and the school that had kind of squeezed him, I think. And he ended up going to college in the territory of Alaska. um And then my mom ah separately, and they didn't know each other, she came ah probably many, I'd say maybe eight years later. And it was because the University of Alaska had so few women, I think they gave her free tuition or something. So they met there. And then um during Project Chariot, which was you know the government wanting to bomb Northwest Alaska with nuclear weapons, my dad was working um in the Arctic studying caribou and he um

00:05:14

Speaker

really liked being out on the land and living, he ended up living in a sawed igloo with this Eskimo couple. You're supposed to say Inupak nowadays. And um they um taught him that life, I guess, or you know aspects of it. But then he he really liked it. And so he basically dropped out of his job prospects with with science and biology and just wanted to be closer to the land than you generally are as a biologist.

00:05:44

Speaker

closer to the animals. and And so when they moved north, um and I was born there that that first winter, I think a lot of the questions you had about, you know, what do you, what do you want for your kids? And everything was just not even remotely on their radar. They just kind of like happens in the world. So they just suddenly had kids. I guess what I started to say earlier is that my mom was definitely not living her dream. It's stuck in a cave with babies crying and, and my dad's crawling out that tunnel every day and hooking up his dogs and his grizzly bears and wolves and whatever.

Relationship Dynamics and Inupiaq Values

00:06:17

Speaker

It's just like this, um, whatever you said about living the cabin life, it was a

00:06:22

Speaker

huge amazing life he was living in my mom was stuck in with us whiny children um and then later I think yes definitely my mom was like would have liked to get us out to public school and all this stuff and and she worked hard to you know get us correspondence books so we could do homeschooling and all that but somewhere in there I'm sure there was some pretty strong tension between my my dad's dreams and and her maybe watching out for the kids. That's interesting. You mentioned this this tension because I was going to say earlier, like I feel like a couple's relationship book should be written by like a couple who's who's done something like this. you know how How to survive your spouse when you're stuck with them for six months in a cabin. um because i imagine I imagine you do have to have some strong emotional and interpersonal skills to get through that. so i I'm interested to to

00:07:20

Speaker

so to know what what you saw between them. I saw very little at the time because I was just a kid and we didn't talk about feelings at all because you're trapped with four people in a sad igloo year after year out in the wilderness. you I think there's a lot of adversity and hardships and bringing up ah mental hardships was was maybe too much but um it was later I would say looking back as the years went by and, you know, trying to have my own relationships saying like, you know, realizing how terribly hard it must have been. um And I think there's also some Midwestern, you know, just keep quiet type of no attitudes.

00:08:04

Speaker

and then um And then if you mix in the Inupak, I'm noticing, you know, i I was raised with a lot of Inupak ways and Inupak values and stuff. And ah right at the top of Inupak illiquidate values is hunter success and avoid conflict. And so when you talk about relationships, we tended, a lot of us, to not be not be good at relationships. We just avoided the um delving into that and um and it doesn't always lead to good things in the end, avoidance, but um but but it's a way of life. So that would be kind of the theme of the Inupiaq's relationship guide to a marriage is just avoid all conflict. Yeah. yeah i mean um Nowadays, you know, you got to be politically correct and I'm a white guy and not supposed to be talking about other people's way of doing things. but

00:09:01

Speaker

Um, yeah, we, Akachek and I joke about that a lot because, um, it doesn't lead to healthy relationship. I'm curious what it was like for you growing up. Like, did you, were you just doing your own thing or did you, were you just doing what your, your, your mom and dad were doing?

Skills and Self-Sufficiency in Isolated Living

00:09:19

Speaker

A lot of what um my mom and dad were doing. So my dad um would cut boards with a handsaw hour after hour um in the middle of the house. He would make sleds in in the tiny little house we had um picture being in a in a bedroom and then somebody's making a sled for six months at six weeks at a time in the middle of it and that includes like bending the wood you'd steamer you know steamer going steaming the wood and big spruce tree playing down in a curve to bend the runners and and um and my mom

00:10:01

Speaker

cooking or my dad ah bringing home in a Wolverine and skinning it on the floor and there at our little table, my brother and I would be doing our, you know, homeschool work. And um so everything was absolutely mixed together, which also resulted in, um you know, my dad teaching us how to sharpen a knife at a pretty young age. And My mom did a pretty good job of ah like teaching us to knit at probably four or five years old and my brother and I love knitting. Knitting is just an example. We also did stuff with pencils and knives and we love carving spoons and um

00:10:41

Speaker

Sawing up caribou leg bones to make rings and all sorts of crazy stuff, but we loved We loved we would knit Just so we could pull it out. That's it. I joke now that it's the the first video game with the knitting you did there is something about being ah intensely ah bored child that leads to you know the the the joy of going out and and playing in a mud puddle. Maybe bored is the wrong word, but um energetic without all this modern crap to ah entertain you. You had to entertain yourself. By the time I was nine, I was i was born pretty very premature and ah you know very small my whole life. and um

00:11:27

Speaker

And by the time I was nine, I was making my own dog sled. I made my own dog sled over the course of ah many months in the house when I was nine. And and that was all um from my dad being, you know, this is how you use a back saw and this I use chisels and this I use brace and bit and all hand tools. I think it all led to self-sufficiency and and um Terrible, and terrible, incredible imagination. my My imagination is just on the go constantly. Are there any drawbacks to you know not having that broader school system, not having tons of friends or anything like that? Do you see anything in your life now where you just wish wish were developed when you were a child?

00:12:12

Speaker

Oh, absolutely. It's incredible. I have no musical ability. ah There's no music. um I have face recognition recognition blindness. I can't recognize people, even though they're all you know in ah small villages that I grew up with.

00:12:28

Speaker

um i yeah I think the parts of my brain that you ah grow, that recognizes names and faces and and all that just doesn't exist. it just It's like a cliff where you're just dumping your household items over the cliff. I just never see it again. um wow and um And it makes it incredibly hard in a small town when you don't recognize people that you're supposed to. ah because then everybody decides that you're arrogant and unfriendly and I just don't know who they are. um um And then um i I can only speculate most of this stuff but I joke like I never went to middle middle school so I never learned anything that whatever you learned in middle school I never went.

Observing Nature and Writing Journey

00:13:13

Speaker

yeah yeah and um And then high school, I only went for a short time and because my mom got sick and and people were, um you know, hideously mean to me. And the only thing I learned was that ah kids are mean. And um no, you know, i never I didn't have any friends or talk to anybody or any of that. So, um yeah, I think there are. um giant drawbacks. um and It's almost like my comment my ah analogy about the volume being turned up. I think I was never meant to be a writer. I i can't spell. i i It was all an accident, but I don't think any of that would have

00:13:56

Speaker

ah developed in my brain if there hadn't been all these other deserts ah around. I guess when I think about humans, my mind goes back to animals. And I wonder, maybe other regular humans, when they think about animals, they can revert to humans. Like, I think about my bonehead uh, you know, growling and protecting his caribou bones. And, and then my new puppy Flint went over and leaped on his head and started booking his little puppy teeth and boneheads eyeballs and, uh, and boneheads just growling away. But at the same time, looking up at me, knowing he's going to get clubbed if he, uh, tries to kill the puppy. Um, and all those little relationships the dogs had to me.

00:14:50

Speaker

I don't know how to say this, but it was like I was looking at at reality or looking at a fox always trying to um steal fish at night from the dog food pile. They're my ah reality of of relationships. And then I look at humans and I'm like, oh, wow, they do that too. You know, they're always kind of. And I know, so I know some native groups, you know, they revere animals or even mountains to the point where they won't even say the name of the animal, like out of disrespect. Is there a certain animal? And I know you you love your caribou. Is there certain animal that you particularly respect and revere?

00:15:28

Speaker

Wolverine. Yeah. Wolverine. Why Wolverine? Well, I've joked for years about myself being a Wolverine because I'm um kind of about the same size and small and muscular and short legs. But if you do um spend time out there where it's, you know, really tough making ah go a go of it, ah Wolverine are about the toughest, most amazing animal at surviving in the Arctic, keep to themselves, they're shy. All this reputation about them being devils and evil is, I think, wrong. um They do react pretty badly if you catch one in a trap. It it does become quite devilish. But um yeah, their ability to live off of old buried bones that were left by wolves or bears two or three or four years ago and

00:16:21

Speaker

um Their ability to go up a mountain um just basically tirelessly up a vertical slope and then down the other side and up the next mountain and And on and on. and see yeah You seem to be describing to tenaciousness and resourcefulness and a lot of stuff that we humans would love to live up to. I want to get some other animal stories from you. I wanted to share an anecdote. um This is probably my most noteworthy experience with a non-domesticated animal. I remember I was in Coldfoot, Alaska working there for the summer and I was walking down the Slate Creek Trail.

00:17:02

Speaker

um with my girlfriend at the time. And out of the woods came this little bird kind of walking over to us. And it was just in the state of alarm with this big beak kind of flapping open. And it just looked terrified. And the natural thing to think was, oh, this this has been abandoned by its mother, or the mother was eaten or something. And it just kind of stood right next to my my my my leg.

00:17:29

Speaker

And my girlfriend scraped all these mosquito carcasses off my calf and rolled it into a ball and fed it. And then we just kind of walked off and felt terrible for leaving this thing alone in the wilderness. And I can just never forget that um experience. I'm wondering if you could share a noteworthy interaction with with an animal that's not domesticated.

00:17:52

Speaker

Across in the hills there, Igacuk Hills across from Kotzebue Sound was an old a white guy that went north after World War II and then lived out there for the rest of his life with his Inupiaq wife. and um And one of the things that he ah ah told me was animals are individuals. And he was ah very adamant that I learned that. and So he was very right that the impulse is to say, you know, beaver do this and eagles do this. And, um, he was trying to get me to be aware that, uh, that like humans, some eagles are, um, like fish and some would prefer to chase rabbits around and some might ah stop and want to peer in your window and see, uh, you know, what you're up to. And I tend to. be be slightly disparaging of men and and males. and And so when you watch caribou, the females um lead most of the time. And the man and man, the male the caribou, i I say they're polishing their antlers, which they do, you know, and then they're showing off their antlers and then they're fighting. And um so one fall, caribou were migrating and this was, they were passing the a community in Kotzebue there and so lots of gunfire, lots of orphaned calves because people were shooting the the females. Calf was orphaned on the tundra, curled up, and just going to you know probably die

00:19:32

Speaker

why the migration is just passing, you know, thousands of caribou going by and, and one bull, um, went over to it and this is directly after the rut. So the bull stopped eating during October and have a big party and lose their fat. And then directly after the rut, they, the bigger ones lose their antlers first. And so it still had its antlers. It was famished and starting to eat again.

00:19:56

Speaker

ah digging you know down through the snow to get lichens and vegetation. and ah It stopped at this calf and um and kept nosing it and and getting it to stand up and then kept waiting for it. and It was getting this calf to migrate and to to move to carry on, you know keep keep going. and um I've never seen that before or since and ah you know in my joking, I would have never given a bull credit for ever doing that. It was very obvious and you know I watched it for a long time and it the bull kept keeping the calf moving and eating and encouraging it to go on. and um

00:20:42

Speaker

um So stuff like that, I think, is good for us um as humans. i and To get back to that me joking about being warped, I really do think that, to be honest, ah humans are terribly warped in the other direction, thinking they're so important and busy. And yeah, all these trees need to go so we can build this condominium or whatever. and um um To be honest, I do think that we're way off track on ah appreciation of all these other nations around us trying to do basically the same thing we are, which is find food and have kids and and not get eaten or killed. I want to touch on on that a little bit later, um but I hope you don't mind if we talk about your your writing for a little bit. And I'm curious when your literary life began, it must have started in the Sawed Igloo, no?

Writing 'Ordinary Wolves' and Process

00:21:37

Speaker

Oh, um if you mean literary writing, absolutely not. um I was kind of well known for ah well known it might you know to my parents and brother, I guess, but as being a slow learner, um just we didn't know what dyslexia was. It was just sort of understood that my brother was super smart and I wasn't. He yeah was so interested in knowledge that ah he just read everything that ah came our way, including the correspondent school out of Juneau when maybe 1973 sent a world book series, 26 books. And my brother, we we would go to the village a couple times a winter to check mail and and maybe sell some skins and

00:22:25

Speaker

visit and and when that box came he opened the box and um Sat out there on the snow bank in the village Even though there's a chance to visit and stuff and started reading and within a couple months he had read all 26 world books and was starting over and so he was just really good at absorbing Knowledge and and then there was me um I took forever to learn to read and Then I couldn't read silently and so my parents and brother would be reading and I'd be reading out loud. and

00:23:01

Speaker

Dick and Jane or whatever it was. And we, I mean, we all read whatever book we could get our hands on. um But I wasn't a deep thinker or deep reader. I just wanted I loved Hardy Boys and it wasn't until a year or two ago I was reading a book on dyslexia and I guess repetitious, predictable type of plot really appeals to dyslexic person, but but still getting to answer your question. I went to college. I didn't even want to go to college. I went to college because I felt like I had no options so there along the river. My brother had left and um so I had no friends and no community and no neighbors. And I didn't know about anything young people could do. So I ended up going to the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. and And when I got there, I had to sign up for classes. and um

00:23:54

Speaker

um all I wanted was a girlfriend and friends and I didn't want any but I took created this class called creative writing and the teacher um Peggy Shoemaker who had just ah moved to the university there she liked my stories and liked and was so encouraging you know you hear about these teachers that change your life and um and it was just an accident and um even then um I was still, I didn't understand, I still don't actually plot or theme or story or endings or anything. I was just writing about and then we saw the bear and then whatever.

00:24:36

Speaker

um So, Ordinary Wolves was, i let's see, if I took that class when I was 18 and Ordinary Wolves came out when I was like 41, so it took 23 more years. My goodness.

00:24:48

Speaker

And I was pretty much dead set on writing a novel. I wanted to write a novel about what it was really like in the Arctic and and I didn't want all this noble bullshit. So you started that when you were 18?

00:25:01

Speaker

well I started writing when I was 18, but pretty quick in there, I was like wanting to write a novel. and ah Basically, it took 20 years to write that. Okay. Well, that's some Wolverine tenaciousness there for you. Yeah. That's really impressive. It totally is in the sense that um you know not too many years in, I had it the first third that I was trying to figure out where to go with and everything and eventually I think I showed the first third to an editor and and then they really wanted the rest and um there was no rest and um and then I think the last five years

00:25:40

Speaker

was even after I got a publisher. It took five more years to get it published. So so just year after year after year and and somewhere in the beginning of our conversation, you mentioned something about writing and maybe it took three years to write a book. and But I always say that um ordinary wolves, I had like 60 seasons that passed. And so when I saw an alder leaf blowing across the snowdrift dragging its seed bear, you know, the berries on an alder dragging it, that the wind the leaf was like a sail pulling its seeds along.

00:26:20

Speaker

That was like 45 seasons into me working on the book. And I was like, oh, I gotta put this, if this makes any sense, I gotta put this in you know somewhere, um which I think it's in there. During that time, I also ended up going to Missoula and studying journalism and learning concise writing and all this stuff, and and also taking creative writing classes. And one of those guys, Richard Ford, I had a class with him briefly, I guess, um said, you know,

00:26:49

Speaker

I carry a a little notebook and write everything down that is interesting. And and and the example I can think of is like um little little pieces. like I was walking on the tundra with my four-year-old daughter and she says, Dad, I think Ravens would be good at speaking Hebrew. And I wrote that down. and What Richard Ford had told us students to do is to write down details and bits of conversation and and descriptions, and and you don't know where you're going to use them, and you don't know if it's an old man that says this, and you insert it in the you know young woman's mouth. in ah

00:27:26

Speaker

in in your narrative. But um when I read Ordinary Wolves now, I just see thousands of pieces that I wrote down and saved and then inserted into an incredibly slow process of creating a book. and And I can see all those pieces when I read it.

00:27:47

Speaker

So it sounds like you're almost yeah you might advise that like slow storytelling. Stories can take decades because you need to accumulate these little details about a, you know, a leaf blowing across the tundra. Well, Ken, I'm a little bit cautious about using the word advise. I hope I don't ever advise people because my writing is so slow. It's just beyond frustrating. People say, oh, you write it, you're a writer and That's not how I feel when I want to sign a book to somebody and they say, um say from um say four can. I seize up. I can't remember how to make an F. man I sometimes switch to two, use the word two instead of four. I go one or two words into what I'm trying to say. ah The one woman wanted me to write it to Sue. I'm like, I don't know how to spell Sue. S-E-W.

00:28:46

Speaker

um I freeze up. I'm writing in this book with a pen. I can't remember. Now, Sue, isn't that what lawyers do? um but how do you but i mean it's My brain is an absolute messy jumble that should never have tried to be a writer.

00:29:03

Speaker

um and yet you're what You're perhaps the most renowned writer in Alaska right now. Yeah, i guess i I guess I think of it like carving ivory where I write a sentence and I start messing with it and I write another sentence and And then I eventually have a paragraph, but i it's just repeat polishing, polishing, polishing. And it's so slow and frustrating that it does give me time to make it better.

Writing Challenges and Motivation

00:29:32

Speaker

But I do see when people write stuff quickly, it often I'm like, I can see that you wrote that quickly. And it's not a compliment. um and I am jealous because I can't type. I mean, I never learned to type, so um i I can, you know,

00:29:47

Speaker

fiddle around and make a word but I can't zoom along and type like other people do um so I can see when people do it I'm jealous I'm envious but I also I'm like gosh you should slow down you could you can write you can type that really fast and your your brain will think And you know how to spell words well enough that you can do that now go back and rewrite it nine or nine hundred times like i do and um you could really be an amazing writer but um i don't have that first part where you know the ability to type in.

00:30:22

Speaker

and and put words down quickly. But I wanted to say something else. I have two things I think that I do have going for me. One is I have this absolute phobia of wasting anybody's time. And so I really don't want to write anything that that I don't run through my own filter so many times to make sure I'm not wasting your time. And then I have part of maybe journalism school in Missoula where I want to be so as clear as possible because I never want to confuse you. Or this thing that I say lead the

00:30:59

Speaker

leave lose your reader. I mean, I just think that's so insulting to lose your reader. So I have that huge ah concern, compassion, politeness, ah care for my reader, which I think makes my writing better. I hope I'm not saying that in an egotistical way. No, no no youre you're saying youre you have kind of an innate ability to self-edit, which I think is a probably an extremely necessary quality to have for for any good writer. And you describe the process as slow and frustrating. Can you describe a moment of writing joy? When I'm speaking, I guess I often say stuff that people are like, wow, how did you

00:31:42

Speaker

say it like that it just comes out that way and i think certain amount of that is part of this connection to the land and animals and stuff that makes it's almost like english isn't my language i mean it is but the the inupia countries that would stop in they would have You know, they're out on the land and in and along the river there, a small sawed igloo. Everybody that passed in the old days, and it it wasn't that many people. First of all, there was the law of the north where you had to ah provide hospitality and food and warmth them to any stranger at any time that showed up at your door. But then nobody would pass without stopping and getting warm and visiting. And so these hunters would speak their English um

00:32:32

Speaker

I think the NUPAC do have just a boiled down version of looking at the world, but they would also have to boil down even more because they only knew like 12 English words. Well, I'm exaggerating, but you know, 40 words or something. One of the things that I use, for example, is I remember that, uh, guy saying, um, little man, big hurry. So he's describing, he was describing a Park Service guy, uh, little man, big hurry.

00:33:00

Speaker

um and It was a perfect description, four words, but I i almost felt like their utterance was an almost subconscious mix with this not many words, you know um not concise. but um you know saving resources you know. And there's something about that in my writing where I just want it to be the perfect description. I want it to be um like when you see a um

00:33:34

Speaker

a Jet coming era air aircraft coming in with a paved runway and the first wheel hits and there's that bark of the rubber, ah the can almost like a seal bark sound. You're like, how do I describe that so perfectly that ah everybody is there?

00:33:57

Speaker

when they read it and and um so I do that with every sentence I guess I'm just I want them all to be um that way. and And what's motivating you to write is it the artwork that you're describing there the whittling away and you know carving the ivory is it wanting to leave a literary legacy is it wanting to share this part of the world what what is it that makes you take on this terrible and um frustrating process again and again. um Interesting. I think it's changed. It's definitely not leaving a literary legacy because I didn't grow up with that white people stuff of all those careers and all that.

00:34:40

Speaker

ideas. they just um it was everybody When I was a kid, everybody hunted and fished and hauled wood. and and ah So we never we didn't have all that doctor, lawyer, famous historian stuff packed into our heads. Protecting the land is is way up on my list of reasons to write. um I think Ordinary Wolves and and maybe some of my early writing was was all desperately wanting to have a book about Alaska that felt like the Alaska that I lived and the romantic books and the leaving out real stuff and ah wolves howling above the glacier and the northern lights and the ah noble natives and all this stuff. I was like, this is not, I live here. I'm right here and this is not true stuff.

00:35:37

Speaker

My brother and I could not stand writing about ah reading a book that was written about Alaska when we were kids. Anything, Chicago, anything, you know, the Constantinople, anywhere, not please, don't make us read a about Alaska. And so I wanted to protect the land, ah protect job hunting and fishing and nature and um not your standard ah environmentalists, you know, protect nature so nature can be out there. I want to protect nature because it was my livelihood and home and surroundings and companions. And um so that was all there. I think I felt like if I could say it well enough and take the great enough photos,

00:36:28

Speaker

people would, anybody, Donald Trump, Elon Musk, all those people would be like, oh, oh, okay, I see now, yeah, we should protect the earth. And um so I think I was just like being a Wolverine about it. Like all I have to do is do it perfectly enough and and and everybody's going to see how important this is.

00:36:49

Speaker

And somewhere along the line, I think the thing I did was wear out my idealism um and be like, oh, I don't know if I'm allowed to use the F word on your podcast. Go for it. Fuck. It's just tough. Your question is about motivation. I think those those were my past tense motivations. um Now it's harder because I get so frustrated with humans for um you know, wanting to watch Kim Kardashian and I'm like,

00:37:25

Speaker

ah i Why don't you like my books more and her less? And my books sell, you know, very few copies. So it's not like it supports me. So there's not that back pressure of ah monetary gain, like, oh, if I write, I'll make money. If I don't write, I'll do something that could, you know, pay for something. But but writing tends to be the least ah productive financial thing I can do. So I think I am at a low point. And I actually, after my caribou book,

00:37:54

Speaker

I was so frustrated with the the outcome of that that i um that I basically haven't been writing for for three years now. Oh, no. i'm I'm sorry to hear that. Are you at least gathering observations like you did? I'm not. or oh yeah no I have a little stubby pencil that's kind of all shiny from being in my pocket. I haven't written anything down in and five or so years now. i just What does that feel like? Does that feel like you've kind of lost a bit of yourself? Yeah, definitely. and it's been ah It's been a long-term thing. It's almost like I'm a little bit more accepting of not writing now, but it's felt

00:38:35

Speaker

Pretty bad. I really do wish it wasn't quite so slow and quite so frustrating to make it happen. I'm in the same place. I mean, um, I'm, I'm trying to publish a book and then I realized I have like no platform anymore. So it's just like, let's start a sub stack. Let's start a podcast today to just today. I signed up for a tick talk. account because there's like this thing called like hashtag book talk and i've I'm seriously in the process of debasing myself just to kind of keep the the career going. But let's get back to your your writing for a second. One of the things I love about it is the

00:39:12

Speaker

The tone of it sometimes there's like this melancholic tone that's just kind of just beneath the surface and you can become quite lyrical when you're describing animals and the land but that that that lyrical tone is not there for long and I sense that's because the land the animals your way of life.

00:39:32

Speaker

It's always under threat, under threat by people. So how does watching, hunt say, hunting tourists come up and kill an overabundance of Caribou? How does that affect your your worldview? It's tough. you know i ah Right now, with the Caribou stop migrating in their normal pattern the last four or five years,

00:39:56

Speaker

which has led to local people shooting lots more moose bears, which is made so along the river you don't see moose in bears and you don't see caribou because they stopped coming. um And so there's this huge loneliness, there's this huge ah Disappointment in humans a lot of it makes me write less because I don't want to just be whiny and say, you know I miss animals and yeah that has made me ah write less and and feel pretty bad about um you know, how we're we're treating nature and we're and where we're headed and I feel like I'm slightly missing your one of your questions. Would you say that you know your observations have gone so far to kind of spoil how you think of humanity? Has it gone so far as to make you misanthropic or do you have enough people around you to kind of balance things out?

Social Dynamics and Cultural Pressures

00:40:51

Speaker

No, I don't have enough people at all. i have um

00:40:54

Speaker

old friends that lived thousands of miles away, but ah basically I'm slightly, I shouldn't say slightly, I feel very ostracized at home. There's a lot of reasons, there's race, ah has there's always been a lot of racism there between the animosity between the races. And then um when my books came out, um sadly enough,

00:41:19

Speaker

Inupiaq culture and maybe part of white culture too, but there's this feeling, especially in the Inupiaq culture, you you get a million dollars for each book. And, um, I don't know about you, but ah I got $1,500 advance on ordinary wolves. And, um, I got $15,000 advance on my caribou book, but basically it's, you know, pennies an hour if you're lucky on in writing, but, but that's not the feeling at home. And so, but if you mix that within you pack culture, which was very fierce about, uh, people staying even. So if you had two sleds and I had no sled, I would go.

00:41:59

Speaker

and hang out in your living room, not living room, your only room. Hang out in your house, in your cabin every day and drink your coffee and say, oh, I sure need sledge. And the next day I'd say it again and again until you loan me one of your two sleds. It sounds really annoying.

00:42:16

Speaker

Yeah, well, you know, but then white culture has Elon Musk and all these people that are yeah money grabbers and, and the INUPAC culture was, was pretty ah adamant about things being more even. But when you write a book and somebody decides you're rich forever and you're not, um,

00:42:37

Speaker

then everybody treats you different. And if you loan them an axe, well, then they're just like, oh, he's lucky. He's got a lot of, he got any much axe, you know? And and that's been ah a real downside of of writing and for me at home. All to say that um if you read back through um my book, Swallowed by the Great Land, it's ah short stories.

00:43:02

Speaker

Almost every one of them has interaction with humans and out on the land, usually you know lots of bears and wolves and whatever, but but some Inupiaq hunter showing up or or some stray yeah white biologist or something. um And I have so little interaction with humans anymore now, kind of a recluse. That makes it hard to write too because one of those teachers, I think it was Bill Kittredge in Missoula years ago, was pretty blunt. He was like, Seth, you know, we're humans. We like stories about humans and there's only so long I'm going to read about you out there

00:43:46

Speaker

with caribou until you know there's some that human interaction too he's he's totally right very very great advice for a for a nature writer but anyway yeah though all that stuff is um has squeezed my writing um and i'm going to say one more thing and i'm probably not supposed to say it but the whole woke Bullshit thing that has taken place where you can't say this and you can't say that and on and on is really hard on ah Being a writer too. I'm not ever setting out to say bad things about

00:44:24

Speaker

a culture and as a writer you want to speak as and write as freely as as you can you feel really kind of um prevented from doing so when you have all these sensitivities that you have to worry about so it doesn't sound like the liberating artistic process um that you would like it to be and i wanted to touch on some of these thorny issues because it's interesting like ordinary wolves came out way back in 2004 and since then you know the country has experienced some cultural flashpoints around race everything from the murder of george floyd to a push for diversity equity inclusion called to defend the police a lot of self loathing among. ah Liberal white people.

00:45:09

Speaker

And I heard that you yourself has been have been called racist. I'm wondering if you can kind of describe the circumstances behind that. And I'm just wondering what this this kind of culture war looks like from all the way up there in Alaska or if it's if it's there um right in your village.

00:45:29

Speaker

Oh, it is. And it's it's absolutely fascinating and and ah amazing and would be so elucidating to be allowed to write about it. And that's the part that that drives me bad is for maybe five years, I've wanted to write a piece for the Atlantic Monthly warning the woke people about the dangers of being woke, which I always equate to getting Donald Trump to be president.

00:46:04

Speaker

um i've i've said for more than five years that um the pressures from that side and I felt them pushing me and I don't, you know i'm sorry to say it, I'm not excited about Donald Trump. I felt them pushing me and I'll try to explain, but I was raised in a lifestyle where if I went to one of the villages or fish camps, people felt absolutely comfortable saying bad things about white people all the time. you know Not just the the the kids in the village you know wanting to beat up the white boy, but ah thinking that white people shouldn't be allowed to hunt and white people shouldn't be allowed to fish and and all this stuff. and I'm not trying to say that in a bad way, but I'm trying to say that um I assume

00:46:53

Speaker

maybe somewhere in Alabama in the 1920s or some of the opposite going on. And we had plenty of racism going on in the Arctic and various types of racism in Kotzebue. But then if you flew south to Anchorage, it was sort of the opposite, you know, native, white, white, native. And um and then came along came this, um you know, maybe whatever you call it, the um revolution.

00:47:20

Speaker

And I feel like It's made local people more aware of the way they treated me or white or white people, which I saw as for a little while, like, well, this has the potential to be a good thing. Because they were just kind of reflecting on how, you know, you were the, the butt of the jokes for, for so long. And that's, that's a really interesting dynamic. And, but the other really fun thing that would take place is like my fish, the fishing, commercial fishing for salmon, my fishing partners. Um, we would just harass each other terribly about,

00:48:01

Speaker

ah race. So my ah one fishing partner would call himself a half breed but I don't know if you were allowed to call him a half breed and then he would um he would make fun. Oh, greedy white guy got to my fishing spot first. And I would say, well, I was ah my native guide wasn't here. I guess he was sleeping in again. And so we're just really um hard on each other, which I think is actually not a but bad thing. It kind of relax things. It kind of just kind of ah allowed you to kind of vent some of those. Yeah, there was never a moment where I wasn't horribly embarrassed to be white. And The new school teachers would get off the plane in the fall and I would be like, wow, they're not embarrassed to be white. How can that be? This was me as a kid, you know. um And my main goal ah in, ah you know, getting to be 18 or 20 or something was to learn to play guitar.

00:48:59

Speaker

become Eskimo or In fact, whatever you want to call it, be six foot tall or something. I didn't want to be a lawyer or doctor or anything. I think it was all the way into my maybe late forties before I finally started to stop being embarrassed about being white.

00:49:17

Speaker

oh You seem to be describing kind of identity politics run amok where you think people less as a person and more as the the identity group that they come from. And that can feel very dehumanizing. You can feel kind of unseen and misunderstood. And I you know i do speaking events. I've probably done like a hundred at college campuses. And I'd say at like roughly half of them, I get a question, you know have you reflected on your privileges as a ah straight white man. And there's like there's an interesting question somewhere in there, um but i I emotionally process that in ah in a negative way because I feel like I'm being seen as a you know demographical group rather than just Ken, you know a person. and that's And that's how I want to be seen as this very

00:50:13

Speaker

complicated person with a whole bunch of different traits as we all are. So yeah, I ah really feel where you're coming from there, Seth. Yeah, that um that's the part that I feel like is probably detrimental. I i guess ah it goes back to nature for me where I feel like there's all these balances.

00:50:35

Speaker

And that's what I was trying to explain about Trump and and the and the far left is that everything is everything is a balance. And so if somebody ah ah shouts at you for being a white man, there's a cause and effect. there's a bad I mean, are they going to push you in some direction on a teeter-totter, a balance? And if so, that's fine. I mean, it's it's just it's how nature works.

00:51:06

Speaker

But what is the result? um And that's the part that's made me incredibly nervous about this. I don't know how to describe it. that's I use the word woke, but this this what's taken place in the last few years is not that any of it is good or bad. What is it going to make happen? And my my ah fear was that um white men are Rich, powerful, strong, and... um

00:51:38

Speaker

and pretty ah good at getting what they want. And so if you push on them, what are you going to get for that ah pushing? um And I have tons of experience because I got pushed on. And I noticed that it changed me. And so that was where my concerns were. I wasn't like, um oh, I can't take this. I'm i'm the king. i'm the i'm used I've been treated that way my whole life. I'm used to it.

00:52:08

Speaker

I was concerned about what was going to happen with people that weren't. And you're basically insinuating that identity politics has pushed people, particularly white men, to the right, resulting in Donald

Connection to Alaska and Storytelling Potential

00:52:22

Speaker

Trump. And you're not the first person to say that. Am I getting that right?

00:52:26

Speaker

Yeah, and I think if you take the the news and Trump and and and all that aside and just said, let's talk about caribou hunting. Sorry, I mean, I know a few things about caribou, but I know a lot about racism.

00:52:40

Speaker

Um, but I'm not allowed to write about that. And, and, and that's the part that I find to be just, just stupid and counterproductive. Um, I just happen to be raised in a different manner. And so I'm a perfect person to be speaking about it, but I can't because I'm a white guy. And I can, I can sense your frustration there. Like the thing going through my mind right now is what, why do you still live up there in a, in a village where, you know, you're not.

00:53:09

Speaker

entirely understood or appreciated. Climate change is coming. The caribou herd is diminishing. what What is it about your neck of the woods or your neck of the tundra that that makes you stay up there?

00:53:23

Speaker

Well, that's kind of a little bit of an interesting question because why are you staying on Earth? um um that the i There's no place like the, you know, you've actually been there, but the in my mind, there's no place like the ah Northwest Arctic for freedom of life. I mean you can head out in any direction and kind of be at your own ah abilities or what ah controls your day and your activities and your ah your ability to haul a load of firewood or or find animals or something and I don't feel that at all in Tacoma.

00:54:05

Speaker

Um, first of all, I feel like I would end up homeless in about 12 days, but I don't feel that way. There's not that openness of land and nature and, and that interaction. And, and so I, I spend a lot of time out on the land. My, my, my life is really divided into, uh, seasons and food, um, collecting salmon, collecting caribou.

00:54:31

Speaker

and then springtime I'm collecting geese and fall time I'm collecting cranberries and and so my life is tied to that land in stories and photographs and and food and then the freedom I guess. I wish I could talk to our country more with writing or yeah I think I was about on the verge of ah switching to comedy when this ah uh, whatever you call it, social justice revolution came along and, um, and I don't feel a comedy is a good, uh, a good example. I mean, how would, what do you love to make fun of nowadays? Well, mean, I wish you would keep writing because I mean, it sounds like, and you'd kind of described earlier that you you maybe don't have as much fodder because you're you're not interacting with people as much, but from what you're describing,

00:55:25

Speaker

of of the kind of the village dynamic in Kotzebue. It sounds perfect for a black comedy. um yeah it's it i'm not quite sure what that you know ah Black comedy means, but i I think I know what you mean. Just darkly comic. Oh, oh yeah, no. um I write sentences in that book every day in my mind, exactly what you're talking about. it's It's perfect. And I have so many examples. like my and One of my other fishing partners will will call me up and say, yeah um just start in like on white guys or something. And I'm like, hey, I'm white. And he's like, anyway, I don't know what you're talking about. and um

00:56:06

Speaker

And that acceptance is it's like everything else I guess I'm talking about. The volume is turned up. by i have I have harsh treatment and I have ah acceptance both with the volume full blast. and ah I think it's good for writing. it's just The local people would accept it if I wrote the black comedy you're describing.

00:56:26

Speaker

Would the New York publisher, I feel like things are changing. I think things are changing before our eyes. And I think the election of Donald Trump, who I like, you don't like at all. Maybe it's kind of sent a message to the culture that we need to kind of shake things up a little bit, but let's let's end on a cultural note. Um, what, what did you want to recommend? I always like Steinbeck for, um, teaching a person how to read, uh, sorry. Right. Um,

00:56:54

Speaker

There's a tiny little Steinbeck book called past The Pastures of Heaven. And I think it's a really good example of ah land and people and and and idiosyncrasies of humans and and then just the ability to within a paragraph or two Steinbeck can have you in a place and and have characters that you're you're in their farmhouse with them. And that's a great book for ah teaching a person how to write ah concisely.

00:57:25

Speaker

Um, obviously I like, uh, like Louise Erdrich is, uh, many of her books, uh, Native American writer and, uh, Margaret Atwood, the robber bride, amazing ability to tell a story and build characters. Um, the last book I started, which, um, I, uh, re working through really slowly is called Anna, Anna men's world. And it's about, um, maybe you've read it, um, just all the different, not all the different, many different ah creatures and their absolute ah difference from us and the way they sense and experience um the world and whether it's an ant or a bat or elephant using ah smells and ah sounds and sight significantly less probably than humans. I'm finding that to be really fascinating but it fits in with my world view which is I have a hard time not talking to a

00:58:25

Speaker

a raven or a but fireweed.

00:58:31

Speaker

I'm going to recommend a book that's been on my nightstand for almost four years now. um And I don't know why I keep it there, because every time I pick it up, i I'm liking it. But it's just sort of dense. It's called The the Dawn of Everything, written by David Graeber and another David. There's two Davids who wrote it. And it's about What are those like history of everything books kind of like sapiens or guns germs and steel by Jared diamond except this one just tries to really up and how we think about human history it's saying that you know cuz we typically think oh we were hunter gatherers then we were farmers then we kinda specialized work then we were.

00:59:14

Speaker

working in factories and now we're just, you know, working in an Amazon ah warehouse. He's making the claim that it was actually a lot, there was a lot more flux foraging societies. They did a little farming. Farming societies did a lot more hunting. um And he he makes the case quite ah persuasively that ah Native American philosophers, he points to this one especially, ah I think his name was Candriano, influenced the French and American revolutions because these you had these Jesuit priests who would come and travel there and and speak to these Native Americans. and

00:59:56

Speaker

kind of bring back these egalitarian ideals, which just kind of an infected the European brain. So I'm really enjoying that right now. I hope I can finish it in 2025 because it's already taken me a few years. Well, that's a really interesting concept that the movement of knowledge, in inest infestation of knowledge. um Well, there you have it from um ah master of of words. um And just but on behalf of all your fans, Seth, I hope you keep writing and I hope there's more books to be read. so I really appreciate that. that some That's what keeps us going. I think probably the same for you is people liking what you do is a really, really huge part. And we don't need to get rich. We just need to also like what we do. There you go. Thanks so much for coming on, Seth.

01:00:50

Speaker

Yep. Good, Ken. Thanks for what you do.