Dr. Lawrence Fung - Understanding and empowering people on autism spectrum

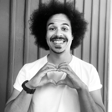

Welcome to this weeks mental race podcast episode, where we'll dive deep into the rich world of neurodiversity and autism. Our guest is Dr. Lawrence Fung, a renowned psychiatrist and a pioneering figure in the field. Dr. Fung is an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, where he directs the Stanford Neurodiversity Project. Dr. Fung's research and clinical work focuses on improving the quality of life for individuals with autism and other neurodiverse conditions, as well as creating more neurodiverse friendly workplaces and schools.

Adding a deeply personal dimension to his professional expertise, Dr. Fung is also a father to a son under the autism spectrum. This personal connection partly drives his passion and commitment to advocating for acceptance, support, and empowerment of the neurodiverse community.

Dr. Fung haș said: “We need to build identity based on strengths, not on diagnosis”

In addition to empowering individuals, Dr Fung explains how improving person-environment fit for neurodiverse individuals can also be good for business.

So join us as we explore Dr Fung´s groundbreaking work and gain insights into his journey both as a researcher and as a parent.

See more about Dr. Fung and his work here:

https://med.stanford.edu/profiles/lawrence-fung

https://med.stanford.edu/neurodiversity.html