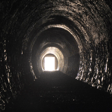

The Apocalypse

In this episode, Megan and Frank examine the Apocalypse. How should we define "the apocalypse"? How does religious apocalyptic thought apply in a secular context? What are the dangers of apocalyptic thinking? And why do we always seem to be in the end times? This episode pays special attention to the book Apocalypse Without God: Apocalyptic Thought, Ideal Politics, and the Limits of Utopian Hope by Ben Jones. Other thinkers discussed include: Machiavelli, Hobbes, Engels, and Rawls.

Hosts' Websites:

Email: philosophyonthefringes@gmail.com

-----------------------

Bibliography:

Ben Jones - Apocalypse without God

Revelation 1 NIV - Prologue - The revelation from Jesus - Bible Gateway

The Rapture Was Predicted to Happen Today. TikTok Has Some Advice. - The New York Times

Opinion | An Interview With the Herald of the Apocalypse - The New York Times

Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy — Harvard University Press

Roland Boer - Revelation and Revolution: Friedrich Engels and the Apocalypse

-----------------------

Cover Artwork by Logan Fritts

-------------------------

Music from #Uppbeat (free for Creators!):

https://uppbeat.io/t/simon-folwar/neon-signs

License code: ZFG8LUQL3TOVMSUP