Become a Creator today!Start creating today - Share your story with the world!

Start for free

00:00:00

00:00:01

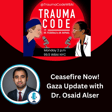

Physician wellness with Trauma Code and Dr. Sophia Ob/Gyn

We discussion physician wellness, recognize secondary trauma and suicide among healthcare providers with our favorite OB-Gyn on the radio Dr. Sophia Lubin.

Music by Alicia Keys.

Transcript

Introduction to Trauma Code

00:00:14

Speaker

Trauma code to New York City, trauma code to WBAI. I am Dr. Simon Fitzgerald, a Brooklyn trauma surgeon and surgical intensivist. And I am Dr. Cassandra Rafael, an adult and child psychiatrist.

00:00:28

Speaker

Welcome to Trauma Code. Together we will focus on healing of mind, body, and community from trauma. We'll discuss how wellness fits into the culture at large. Join us on Monday at 2 p.m. on WBAI.

Interview Preview with Dr. Sophia Lubin

00:01:44

Speaker

Welcome back to The Trauma Code. Can you guys hear me on the line? I am live, but I am not in studio today. This is Dr. Simon Fitzgerald, and that was just Alicia Keys, superwoman. and I can only step out for a minute and have some clinical obligations, but we have an excellent interview today with an OB-GYN, the first GYN we've had on the show, Dr. Savio Lubin.

00:02:08

Speaker

An excellent OBGYN, delivered my youngest and also a Haitian American with her own a podcast called, I think, Dr. Sophia OBGYN. And we're going to be talking about physician wellness and i I'm anticipating she'll be back on the show in the future. And I'll fade into

Dr. Khaled Al Sur's Release and Regional Violence

00:02:26

Speaker

that in a minute. But before we do, I have one piece of good news and update about our partner, Dr. Khaled Al Sur from Nasser Hospital.

00:02:36

Speaker

The first author on the Lancet paper that I participated in recently who was in Israeli custody for months since March was just released earlier today. ah So he's, you know, as much as you can be in Gaza, he's a free man. So we look forward to talking with him and working with him. And even though the violence is escalating in Lebanon and that's something we'll be paying attention to and it continues in Gaza, there's one piece of good news and perhaps a path towards a future where we can work together healing people in Gaza. So weíll talk more about that in future weeks but for today we have an excellent interview coming up with Dr.

Introduction to Dr. Sophia Lubin

00:03:12

Speaker

Sophia Lubin talking about issues of physician wellness on the trauma code. Thank you for listening to New York and thank you for your help in Studio Regi.

00:03:24

Speaker

Welcome back to The Trauma Code. This is Dr. Simon Fitzgerald in studio with my lovely co-host. Dr. Cassandra Fael. Happy Monday everyone. And we have on the line a special guest. I think the first OBGYN we've ever had on the show, correct me if I'm wrong.

00:03:41

Speaker

Dr. Sophia Lubin. Cassandra, Dr. Rafael, do you want to introduce Dr. Lubin? Absolutely. She's very dear to me for a reason I'll share later on. Dr. Sophia Lubin is a Haitian American board certified OB-GYN working for over 15 years in her native New York City.

00:04:00

Speaker

Dr. Sophia currently practices at Symphony Medical, My Wellness Solutions, and Vibrance BPC, where she provides a wide range of services, including routine obstetrical and gynecological care, and aesthetic medicine. She has a special interest in sexual health and wellness, also menopause and surgical interventions as needed, so GYN surgeries.

00:04:21

Speaker

Being a woman's health and well-being enthusiast, she spreads her knowledge and care through social media and has recently launched her podcast, Dr. Sophia OBGYN podcast, where she helps women learn about their bodies and embracing themselves.

Dr. Lubin on Women's Rights and Health

00:04:36

Speaker

Dr. Sophia is also a committed humanitarian who has provided OBGYN relief efforts in Haiti annually. Dr. Sophia obtained her medical degree from New York Institute of Technology, New York College of Osteopathic Medicine. She completed her OB-GYN residency training at Beth Israel Medical Center in Manhattan, which is now Mount Sinai Beth Israel. She's taught medical students and residents in a myriad of settings, including at her alma mater as clinical faculty at New York Institute of Technology, New York College of Osteopathic Medicine.

00:05:09

Speaker

As a practicing OB-GYN, Dr. Sophia uses her expertise to further her other endeavors, including provider training in non-surgical cosmetic techniques, her love of women's rights, as well as supporting women who have suffered from mental illness and domestic violence. Dr. Sophia is passionate about broadening her scope of practice to help women lead happy, healthy, and empowered lives. Dr. Sophia, welcome to the trauma code.

00:05:37

Speaker

Hi, everyone. Oh, it's so nice to be here. Thank you so much for having me. You're so excited to have you here. And of course, whenever you hear stuff said about yourself, it you're like, oh, who are they talking about?

Secondary Trauma in Healthcare

00:05:50

Speaker

ah That's you with all those accomplishments, my dear. so That's you. Dr. Sofia, thank you for joining us. and And there's so much that we could talk about related to your specialty of OB-GYN. I know we talked offline about you know the you know reproductive health in the post-OBS era and and many other things. But actually, the topic that you are kind of most most enthusiastic about in this moment um is not precisely related to OB-GYN, but rather and and you know correct me or or expand on this, but about the secondary trauma um faced by healthcare workers such as physicians and kind of the effect that it has on all of us. Can you tell us a little bit about why that topic is so important to you right now?

00:06:39

Speaker

You know what? It's pretty interesting, um Simon. Part of how I even came to really think about it was from my own personal experience of dealing with some patients of mine and really when I say, you know, secondary trauma,

00:06:57

Speaker

I'm really talking about how we go from patient to patient given their different um scenarios. Specifically for me and my discipline, it comes it it really came to fruition for me um when I had a patient who'd had, she was new to me and she had um just found out she was pregnant.

00:07:22

Speaker

but She was telling me the story of how she was trying to get pregnant and was so excited about having a positive pregnancy test and came in to see me. And all throughout her story, I'm listening, taking her history, doing her, you know, routine exam. And we're both just so excited about the concept that she has now is now pregnant.

00:07:43

Speaker

And so, I say to her, okay, well, let's confirm the pregnancy. I'm going to send you for an ultrasound. And, you know, despite the fact that this is what I do, and of course, it's always a possibility. But when the ultrasound came back that she was certainly far enough along where she should have a heartbeat, but then did not.

00:08:05

Speaker

I myself felt a little devastated because now I had to go back into that room and where we were just five minutes before, so excited, so happy. And now I have to go and give her this you know really devastating news and you know everything changed in an instant.

00:08:27

Speaker

We went from being super happy to being super sad. And I say we because I felt those emotions for her and with her, you know? And literally after, you know, being her supportive person in that moment, she came to her appointment alone. It was supposed to be a surprise for her to go home and tell her husband that she was pregnant.

00:08:53

Speaker

And after going through the motions of that moment, I had to then kind of wrap myself up and go into another room with another patient and be excited and be happy for this next patient patient that I'm going to see.

00:09:13

Speaker

And I remember coming home that evening still feeling very much charged and still feeling very emotional for having to have gone through that experience that day. And though it wasn't new, it's not to say that I've never done this. So it's been 15 years. It happens, you know, all the time, especially when it comes to first trimester loss.

00:09:36

Speaker

But for that particular day, I don't know what ah what triggered me or what have you, but the concept of not being able to take a moment for myself to acknowledge what just happened, not just to the patient, but really also for me. And it made me go back.

00:09:59

Speaker

and think about all of those times that I have been in an emotional setting and and have not been able to take the time out for myself that I also need to deal with that emotional trauma. And in our profession, we are tasked with doing that on a daily basis.

00:10:26

Speaker

And it made me realize we need to do something more. We need to, first of all, acknowledge the fact that we have this constant micro trauma. And then to recognize what that how that actually impacts us. Because when I got home that evening, like I said, I still felt very charged. I so i felt like I just, but my my my cup was completely empty. So I had nothing to give. I had nothing to give to my family. I had nothing to give to my friends or whomever may have called me that evening.

00:10:55

Speaker

And I also wasn't quite sure who to ask for help in that moment or who to rely on or who to ask for support or who would I feel would understand me in that moment. And that's what really brought me to this concept of this understanding, hey, who takes care of the person who takes care of everybody else?

COVID-19's Impact on Healthcare Workers

00:11:25

Speaker

And we talked a little bit about how the crisis of COVID that pulled you know a lot of people into um uncomfortable situations, a lot of morbidity and mortality, um a lot of anxiety, like our coworkers getting sick and things like this. you know i I know as I was a COVID intensivist for three months or four months of my life, that's all that I did. And we definitely saw a lot of death and had to figure out things that we hadn't dealt with before.

00:11:51

Speaker

And you you know you shared your own stories with us offline. I don't know if you want to talk about that, but definitely the ah burnout, early retirement, and we can get into some of the other health effects of that kind of trauma. Do you want to share a little bit ah of of your experience of the of the COVID pandemic and how that influenced your thinking on this topic?

00:12:13

Speaker

Well, yeah, I mean, like many of us, right, we experienced loss in such tremendous ways during the COVID pandemic, whether it was from our patients, whether it was loved ones, et cetera. And for me, particularly, you know, at the time when COVID first started, I was in a group practice and one of my um One of my partners was elderly and my other partner had just delivered a baby on like, March 7th of 2020 and we went into lockdown on March 19th. And so. I, in a busy practice that delivered over 30 babies a month.

00:12:53

Speaker

basically told my elderly, ah you know, colleague, no, you cannot step foot in the hospital. Don't even think about it. We don't know what this is. Okay. And then, of course, my other partner, of course, who had a baby was on maternity leave at this point. And thank goodness that she was.

00:13:12

Speaker

And so it kind of left me with the charge of having to take care of the practice, right? We still had, you know, women were having babies like left and right. It was a busy, busy, busy time. Was I on the left or was I on the right? And people had to find things to do and babies were among them. But ah no, in all honesty, what it meant was that we had to take care of very difficult patients. We had to take care of very sick patients.

00:13:41

Speaker

And in the practice, we had a patient who delivered. She had delivered via C-section. And then two weeks later, developed COVID. And then two weeks later, she was dead. And this was a woman who I took care of for her entire pregnancy. It was her first baby. She was a nurse.

00:14:04

Speaker

I mean, you know, the whole thing in terms of as a setup of, you know, despite being in healthcare, she was African-American and there was just this constant fear of what this thing was and also how we as patient, you know, people of color felt like guinea pigs. We didn't understand what was happening, why we were being treated in certain ways, what was really being offered to us. And so, I remember being on the phone with her and she was at a different hospital. She wasn't even at my hospital when she got, um when she had to be admitted because of COVID.

00:14:51

Speaker

And so it's not like I had anything, any say at all with how she was being managed. And when I would speak with her and I would say, well, she would say, well, I don't want to try this. I don't know what it is. they're They're offering me this new medication. I don't know what it is. I don't want to try it. Or she would say things like, um Dr. Lubin, can't you come and be here with me?

00:15:17

Speaker

you know, and I think that very much rang the most home for me was not being able to be there for my patient, not being able to even just hold her hand, support her, help her feel like she can trust the other doctors were around her, people she had no she'd never met, she'd never she know she had no contact with. And remember, in COVID, everybody who had it was basically being treated like a leper, right? We were all masked up because we had to protect ourselves as well. So if you were lucky enough, you could see someone's eyes, you know? But you really couldn't feel the person, you really couldn't tell, and you couldn't

00:16:04

Speaker

just gain that kind of rapport that we look for when we're dealing with patients. And I just remembered that when she when she did finally pass away, and this was a young woman, she was 32 years old,

00:16:20

Speaker

When she passed away from COVID, I remember falling down on my knees and just sobbing and sobbing and crying like because it was just like if only there was someone who could be next to her to help her see that, yes, i don't we don't know what this is, but we have to take whatever risks that we have to take that could potentially make you better because you now have a four-week-old child that we have left behind.

00:16:47

Speaker

And I think, you know, a lot of us, certainly all of us on this conversation have the cases that um we kind of carry with us as sort of our burden. And I think it was a French surgeon, I don't have his name in front of me, who once said that every surgeon carries with them a graveyard where they go and pray before each day or each case.

00:17:05

Speaker

And we could talk about that a little bit, but I think it's also worth thinking in this moment of, you know, what is the toll on the healthcare workers? And I think, Cassandra, you had some data that you had looked up, some updates on, you know, we know that there's high rates of probably addiction and substance abuse of suicide and self-harm and probably other issues as well.

Physician Suicide Rates and Mental Health

00:17:31

Speaker

Do you have any data to share on that? Well, yes. So earlier this month, actually it was last month, the Guardian had published an article that looked at a study that was recently published in 2024 by the British Medical Journal looking at how physician suicide has changed in the past several years. Previous studies of physician suicide have showed that about one US doctor ends their life daily and

00:18:01

Speaker

by comparison in the UK about one every 10 days. So those are the previous statistics. Now the British Medical Journal article is saying that although the rates of physician suicide has gone down at large, male physicians show little to no difference in suicide risk than the general population. However, for female suicides, the the risk of suicide was For female physicians, the risk of suicide was significantly higher, as high as 76% more than that of the general population. um Male medical doctors, however, did show a higher risk of suicidality compared with other professions um who

00:18:47

Speaker

maybe share the same socioeconomic groups, so who make about the same amount of money, who might live in the same neighborhoods, et cetera. So it sounds like we're all at risk, um regardless of at least sex or gender. And you know i and same as you know working with the COVID patients, I've declared a lot of people um deceased in my time in the ICU and also you know in the trauma bay,

00:19:15

Speaker

ah And maybe there's a way, you know, I didn't i didn't shoot people who come in and and and can't be resuscitated. And maybe I've compartmentalized a way of of leaving that. And often there's not family around, you know, um in that moment, that that rush to the hospital with them, we don't always see and speak to the family.

00:19:34

Speaker

um But, you know, when I was a chief resident, I know one of our medical students committed suicide and my junior resident was the one who discovered them. They jumped out of the dorms right by campus. So definitely ah that, you know, and one of the medical students that I study with went on and committed suicide during residency at a different program. So definitely ah is something that's been present um with me and probably with a lot of other healthcare care providers.

00:20:02

Speaker

so i aren to Recently, I mean, last year there was a female resident, actually a patient descent, who um also committed suicide. And um it just goes to show you that we simply just don't have the right support systems or we're not getting the correct messaging as healthcare providers on how we can take care of ourselves.

00:20:32

Speaker

you know, it's just not coming across somehow. We have this kind of like superhero kind of almost complex that we should be able to do it all. We can handle it all. um And we leave ourselves behind. and But we are exposed constantly to these traumatic experiences. And it it reverberates when we look at substance abuse and when we're looking at things such as, you know, increase in suicide rate. And I can see why, even especially among, like, female physicians, um because sometimes the workplace can be a little bit of a hostile place.

00:21:15

Speaker

you know, um not just the trauma from our interactions with our patients, but also we still have to combat the sexism, you know, and and discrimination and just not feeling like we're ever moving up the ladder, for example. So there's so many other things that really can impact how the trauma can kind of be across the board on so many different levels. I think that, well, one thing I'm going to to share with you both. So it's it is like National Suicide Awareness Month and September 17th was particularly the day that recognizes physicians who have lost their lives to suicide.

Compassionate Language in Suicide Discussion

00:22:04

Speaker

When we talk about suicide, we shouldn't say commit because it's not a crime, right? Because we we want to

00:22:12

Speaker

demonstrate understanding that who we are talking about or anybody who has ended their life was a person who was suffering. And so we say that they died by suicide or ended their life, right? Or ended one's own life. So ah that, I also wanted to say the name of the Haitian resident because I had thought of this. ah Dr. Sophia, when we spoke yesterday and I wanted to write it down, her name was Dr. Nikita Mortimer.

00:22:41

Speaker

Uh, general anesthesia resident. Um, that's right. Right. Rest in power. Rest in power says. Yeah. and And I, and you know what? I appreciate you Cass for, um, making sure that we use the right language, you know, and despite the fact that.

00:23:02

Speaker

we may, you know, think about it and say, yes, why would and commit is such an, you know, we've used it so much that it becomes second nature. And then we really need to start by changing the way that we speak. And so I'm thankful for you for actually bringing the point up.

00:23:20

Speaker

And, you know, we all have somewhat um different patients and they kind of weigh the emotional burden is somewhat different right between psychiatry and trauma and OB.

Stress and Imposter Syndrome in Medical Training

00:23:32

Speaker

And I'd like to hear Cassandra, some of your um some of your thoughts and and experience.

00:23:38

Speaker

on the topic. And as I mentioned, I think the ones for at least surgeons, and i I imagine for a lot of clinical physicians, the ones, like you mentioned, the outcome that was unexpected. um And sometimes, you know, you second guess everything, would there have possibly been a different outcome if something had been recognized differently or managed differently or, you know, was my technique, you know, suboptimal and some procedure. um I think those are the ones that weigh a lot on on a lot of providers.

00:24:08

Speaker

I have to agree. I couldn't agree with you more. I mean, when I think about this particular case of this patient from COVID, I keep saying, you know, she had to have a C-section, but I keep saying, was that a C-section? Was that C-section avoidable? Could I have done it it? Would she have had an increased risk of, you know, just her body being so worn down and um having had a C-section versus had she had, let's say, a vaginal delivery, you know, and so that weighs on me. Even despite knowing that she needed a C-section, I keep saying, well, maybe she should have had a vaginal delivery as if that was possible, you know, that a woman who has a vaginal delivery, you know, just has less, has more, um I guess, strength, you know, in terms of their recovery process, right? I mean, it's major abdominal surgery.

00:24:59

Speaker

That is correct. It is major abdominal surgery at the end of the day. but you know And so it comes with its own morbidity. And so and that played on in my mind for, I don't even know how long. As you can see, I still even talk about it as if it's something I could have changed. right And I think that's an experience that many, if not all of us who have gone through medical school and residency training and fellowship might experience. ah The feeling of imposter syndrome, second guessing oneself. So even that in and of itself when you're talking about medical students who

00:25:36

Speaker

have also ended their life, it's it's as a high stress environment. At every level of this ah preparation to work with patients, it's high stress. so yeah and working with your colleagues and the hierarchy that we have in medicine and, you know. The hierarchy especially and what people feel medical training has to be because it has historically been that if it's it's felt like hazing, you know, in in the past, you know, older generations of physicians will say like, oh, I had to do this. You you guys have it easy. You guys have it light. um And maybe in some ways that's true, baby.

00:26:14

Speaker

Maybe, you know, but at the same time, I think we should celebrate the of how far we've come. Exactly. Of, you know, treating the medical education process with more dignity and respect, right? That each person is a person and that they should still be able to be whole. Like, yes, I know how important it is for our medical training, but there's something to be said with allowing them to have a life.

00:26:41

Speaker

Outside of medicine, right? So, it shouldn't be that we work 110 hours. Like, I remember you know um that we do have things like you know work our restrictions and you know all of the different types of um other influences that happened during the course of our training.

00:27:00

Speaker

right And I think for for whatever it's worth, one issue with physicians in particular is the kind of delayed compensation, deferred gratification. I think if people are unhappy after investing, you know, five years, 10 years. thousand five hundred thousand in medical school Six figures in debt. Big tears. Right. here there's I think some people, you know, and and and becoming much older and and still not not seeing, you know, the the benefits of you if you're not appreciating that moment, then it feels like a loss and a huge sacrifice. And I think ah for at least one of of the the the cases that I mentioned, I think that was a big part of it.

00:27:42

Speaker

Yeah, I can see why. um And you know, I want to think a little bit about how are some ways that physicians can, um you know, how can we deal with these difficult cases and in a healthy way and not these unhealthy coping.

00:27:57

Speaker

um But Cassandra, do you want to talk at all about and without, you know, violating any patients or families of privacy, and anything about the type of cases that that you take care of then and how it weighs on on um on a child psychiatrist differently? We've talked about how, you know, you're working ah with young people who, you know, who presume to have a ah ah you know ah limitless future ahead of them, and also parents who who are not your patients, but at the same time, you have to manage them or with them in a way.

Empathy in Psychiatric Care for Children

00:28:29

Speaker

And I and i i feel a lot, I yeah i don't want to say sympathize, but certainly there's a significant amount of empathy, not just for the the patient who I'm working for, but also the parent who I have to work with. And it's often a pleasure. I think that parenting is one of the things that, I mean, I'll say,

00:28:48

Speaker

perhaps the most difficult thing I've done in my life, but also one of the most rewarding things and and I take it very, very seriously and i I enjoy helping other people along in this process and um helping people be dynamic in the parenting experience ah to learn to be with you know the child that they that they have and that they want to raise.

00:29:13

Speaker

um So I find myself empathizing a lot with the parent who oftentimes in in the settings that I work in the patients tend to be among the sicker of the identified sick children ah in terms of mental health. I say that because as we all know we're in a youth mental health crisis um and so young people are really suffering and Many of them are identified and in treatment, yes, and I work with those kids, but many are not, right? So that's why I say the identified sick kids. um For many parents, especially the parents of children who have something that at least on diagnosis seems will

00:29:56

Speaker

require long-term treatment into adulthood. So I'm talking about children diagnosed with psychotic spectrum disorders or like schizophrenia or a bipolar disorder and and end up needing treatment essentially for life in in many cases. um One of the things that I have to do is to help the parents kind of jump over the hurdle of being intimidated and scared of the child's future to an extent that impedes their ability to actually collaborate in helping the child in the present day, right? So it's work that I enjoy doing, but it's also very difficult because there are some parents who are quite

00:30:39

Speaker

incapacitated by the thought that their child is going to need such long-term care. Psychiatric care was, of course, still very stigmatized among medical cares or types of medical care. So helping the parents get through that is is rewarding but also challenging. But you kind of call them to task and say, look, yeah, we don't yet know what the future looks like.

00:31:04

Speaker

For the kid, we got to see, we got to establish and reestablish what their new baseline might be in terms of functioning, what their schoolwork can look like now, what their extracurriculars can be like now, um and getting used to being on medicine if they have to be on medicine.

00:31:20

Speaker

But we have to be able to do this to make sure that we we got to make each day count in order for the future to look a way that we can be most comfortable with, in order to be able to know and say comfortably that we have done our best for the child. um But it's been a little bit, it's been a little bit hard. It's been a little bit hard for me. At least I would imagine. Yeah. Yeah. But like I say, I enjoy doing it, but

00:31:49

Speaker

when i when I think about what that what that must be like to be on the other end of the conversation, I know it's a challenge. It's a far greater challenge for them than it is for me, really. But um I do feel motivated by it, but it it can be draining to be trying to move the needle for a kid and their parent is kind of dragging just by nature of,

00:32:17

Speaker

having a hard time confronting their reality, if that makes sense. And then, ah so how do you then internalize that or make that, you know, like what what does that look like for you in terms of perhaps that as a micro trauma, you know, because at the end of the day, you are doing and trying to do the best or the most you can for your patient. And like you said, when it comes to working with the parent and when you're not met with um, equal sense of collaboration in our collaboration, right? I shouldn't say motivation, but certainly collaboration because of their own fears and other things that they may have going on in their lives. How is that impacting you? And, you know, like, you know, at the end of the day, I guess I have a lot of faith in young people.

00:33:16

Speaker

I like to give them or ascribe to them, maybe in some cases, more resilience than their parents can, especially when the child is in crisis. I try to remind the parents, look, you're telling me the kid's sleeping all day, all night. Give them something to wake up for, even if it's chores. Give them something to do in the house. The child is not a fragile, like, Faberge egg.

00:33:40

Speaker

you know, give them something to do in the house. If it's chores, make sure that they're doing their homework assignments, challenge their brain still a little bit, you know, doing things like word searches or like drawing tutorials, things that kind of keep the child engaged and using their mind and feeling productive and things that they can actually succeed at um and feel good about on a day-to-day basis because The child, obviously, just as the parent is concerned and conflicted about everything that's going on with the child, it's the child's life, right? And we want to encourage them. So I've like loaded up my office with these kinds of activities for the kids, Legos, all kinds of things that the kids can really just lean into and work on and and get to see a product of and feel good about themselves. And when they do enough of this, they start to kind of have more of a sense of their own efficacy, right? and um

00:34:36

Speaker

I lean in into seeing them enjoying something. I lean into seeing them feel proud. um And that really that really keeps me going at the job, in the job. But also personally, you know i I do my own things to to cope. you know and One of the things that I think probably still in in medicine, we are not maybe doing enough of, or it still may be stigmatized in some ways as seeing a therapist. When in fact, when we're talking about everything that we've been through during the COVID pandemic and helping people throughout that and other difficult cases or difficult circumstances for ourselves and for them, we do need a sounding board.

00:35:25

Speaker

not we absolutely yeah sounding important And the thing is, is that we are going through all of this as far as work is concerned, but it doesn't change what's happening in

Balancing Personal and Professional Life

00:35:33

Speaker

our home lives, right? yeah You know, in terms of, you know, the amount of physicians who get divorced throughout their careers or what have you, who have children who have mental illness. I know that I'm a parent of a child with a mental illness. So I know that the rest the rest of my life is still going on, right? And I still have to deal with the struggles of what's going on at work. And so I have to show up at work and then I still have to show up at home.

00:36:00

Speaker

you know, and so I think you're absolutely correct when you say that we just don't have enough resources or outlets when it comes to how we then can cope for ourselves. um You know, I think that the same way that we as doctors or in healthcare care require that we have, we usually have to do this like annual assessment.

00:36:26

Speaker

yeah so I don't know, I'm sure you guys have to do it in your respective places of work where we have to make sure we've gotten the flu shot, we've got to make sure that we've gotten, you know, our latest TB is negative, et cetera. And I think it we should all benefit, we would all benefit if we also did at bare minimum a yearly wellness check. yeah I'm not exactly sure how to make that, what that looks like, you know, but I just thought about it and I said, well, if we were doing that kind of check in where it didn't feel like we're going to a therapist.

00:37:11

Speaker

right? Where we... If it was standardized, if it was something that everybody has to do. Like everybody has to do it. And not only does everybody have to do it, but it's in a and an environment that is like, you know, anonymous, makes them feel like I can just kind of take a seat, unload if I have to, get some good input so that I can go back and do the thing that I love.

00:37:35

Speaker

right? Like I love being an OBGYN. I just like you my my glass is definitely filled every time I deliver a baby. I went into this because I wanted to be in happy medicine you know and that's what OBGYN is to me. It's happy medicine and so I feel like I know for me, you know, people, one of the things that I do and I still love to do is going to do my nails. Okay. It doesn't matter. Three hours, four hours. I allocate a whole day for this activity. All right. Because it's so mindless. I don't have to necessarily think about anything except what colors and what designs I perhaps want to do. And everybody's like, Oh my God, how do you operate with those nails? How do you examine patients with those nails? And I just like figured it out. because there's no version of me not doing my nails. And that's only because that's the only way that I am able to kind of take like a chill pill just to give myself that little break. Self-care.

00:38:43

Speaker

And I think those are some some good ideas that, you know, um as you mentioned, Cassandra, the role of of therapy for the provider and so Dr. Sofia, thinking about how that can be ah more normalized or institutionalized is just part of our self-care and our self-awareness at work.

00:39:03

Speaker

um and And I wanted to think a little bit more about what are some healthy ways of of coping or or responding to those difficult patients. But I did want to recognize, you know, our show is called Trauma Code, and a trauma code is called whenever they need our emergency services in the hospital. And I think the trauma code that creates the most anxiety in the hospital with everybody involved is the trauma code to labor and delivery. 100%. Because it's usually a relatively young, healthy person,

00:39:32

Speaker

and there's supposed to be two good outcomes and there's a potential for absolutely catastroic catastrophic outcome. You know, usually we're called because someone's hemorrhaging or there's an airway emergency or maybe a massive pulmonary embolus and someone who could either recover and be ah a mother with a baby or um not recover. And if there's a bad outcome, everybody in a hospital is looking at it very carefully. There's a lot of attention right now, particularly in Brooklyn, looking at maternal outcomes. So so with with um that in mind, and I don't know if you wanted to to add on that, but I was thinking about um a case that was sort of of

00:40:15

Speaker

that stuck with me for a different reason in in fellowship. And when I was in fellowship at at Hopkins, I was part of the Baltimore Peace Movement, then called the Baltimore Ceasefire. And one of the things that was being done is that a community of people were showing up in the spaces where someone had been killed and like burning sage and being present and sometimes inviting family and community. And there was a stretch in, um I remember in February,

00:40:42

Speaker

Uh, where there had been like 10 or 11 days without a murder in Baltimore City, which was kind of a big deal. It hadn't happened since before Freddie Gray was killed. I remember when and that happened. I was so happy because my son is in Baltimore. oh yeah oh at college And so one of the next, you know, um and I was present for someone who was killed and then went to the community to be part of this, um to be present, this sort of vigil, this sort of prayer. And because there had been this gap in in people being killed, it ended up being very close after.

00:41:13

Speaker

on the murder and it was like the mother's first time leaving the house and we were like present on that corner and um you know I spoke to her and I said in sort of a public forum like I was you know I was there when he came to the hospital and it was like being present there was so much like power in that space it was like a couple dozen people community members family and then these could sort of community violence, you know ad hoc interventionists, um and I was present and part of that space. and And I do think that it was maybe healing in a way of you know carrying that ah burden with other people of being around death so much without you know locking it away and putting that in in a vault or a graveyard that I that i pray at quietly by myself. And and I wonder if

00:42:01

Speaker

um being able to take part in systemic responses or community responses to the difficult patients that you mentioned, the difficult cases, that you want to do something differently, but obviously you can't go back in time, so how do you do something meaningful moving forward? um I think that it would be a way of of um decreasing the amount of physician burnout is to have another outlet for that kind of um work and response to those cases that we carry with us.

Community Healing and Physician Burnout

00:42:32

Speaker

I am in full agreement with you because any opportunity that we have to share in a moment of healing and in order to do that, we have to first address it and really be like present with it. You know what I mean?

00:42:46

Speaker

and so you know if um and and face it, right, in order to be able to start a healing process. And I think doing that in community, you know, um I think is also, it allows you to always feel like you're not alone. And oftentimes when we have, let's say, on the labor floor, we have a bad outcome we go over it in something called a debrief in order to debrief what happened, who was impacted. um And it's, you know, with all of the medical providers and all of the staff that weren' that were involved in the case because

00:43:28

Speaker

especially, like you said, on a labor floor where we're supposed to be, everything is all smiles. And if you have a physician, excuse me, you have a patient, a mom who passes, or a baby who passes, or both, you know, and then all of the people who are involved in that care um come together so that we can talk about not just what happened in terms of what went wrong or what went right or, you know, those things are important, but more so to address how each individual person is actually dealing with the that bad outcome.

00:44:15

Speaker

um And I do think that that's a step forward towards like the healing process, but I see how what you've described is even more impactful because you have an opportunity to include.

00:44:28

Speaker

in that moment, the ah family, for example, or the community, for example. And I think that that allows us to be able to see the other side, right? um And that healing process. and and And being able to just share in the fact that, hey, I don't know your loved one the way that you do, but I'm so sorry. And and and really being able to just share in that moment of grief,

00:44:58

Speaker

um and allow yourself to even feel that emotion, you know. I think, again, we are so, I guess, trained to kind of move on to the next thing and the next thing and the next thing that we often don't have a an opportunity to to go through that process. I think this also goes back to the point of not just accepting that you training in medicine is not a perfect system. There are flaws in the system, right? So even if at a time, physicians appeared better able to kind of compartmentalize and just move on to the next one, I think that

00:45:46

Speaker

kind of ah excludes a ah part of humanity that I don't see the sense in excluding much longer. I think we have to see each other. you know I think we have to see our patients, we have to see our colleagues, and I think that that will move medicine further for us, especially, here I go on my soapbox, in a system where medical care is unfortunately a privilege. You know, we don't all have it. And ven writing yeah, many people need it and don't have access regardless of whatever their their condition is, they're not going to get access.

00:46:31

Speaker

alright

00:46:33

Speaker

Step one to remedying this kind of societal ill is by seeing each other in the system that we are participating in. right Doctor for patient, patient for doctor, doctor for doctor, nurse for nurse. you know So clinician to patient and vice versa.

00:46:51

Speaker

Well, we'll keep that in mind. and And, you know, if you're just joining us, we're on the trauma code talking with Dr. Sophia Lubin about physician wellness. And and we talked, you know, some ideas ah for healthcare workers and and those around them, those who love them, um ideas like therapy, but also um systemic or community or organized responses to the most difficult kind of um cases or the the most kind of burdensome parts of of the of the work they do and and the patients they take care of. Anything else that that you want to say or take a moment while you have the ear of some healthcare workers and people who love them? I think while I have the ear of ah of us, right the the people who take care of other people, that it it always start it should start with us first.

Importance of Self-care for Healthcare Workers

00:47:43

Speaker

We have to take care of ourselves in order to take care of someone else.

00:47:47

Speaker

It's the old adage of of course, when you're on a plane, they tell you to apply your mask first before you apply anybody else's mask. And I think it's been too long and too accepted in medicine that we keep putting on everybody, putting on the masks on everybody else. And then we succumb to all of the different ills that we talked about earlier, whether it's substance abuse, suicidality, other mental health issues, et cetera.

00:48:14

Speaker

And so I think we need to start taking this kind of like um approach that in order for me to be the best physician that I can be, I have to first take care of myself, right? And in it's, I mean, we are all kind of like,

00:48:33

Speaker

a part of this process where, you know, we're like our worst patients. ah Physicians, you know, we can talk about it. Well, be I can be honest. it I'm like one of the worst patients. I go to the doctor. I call up a friend. Hey, I think I might have this. Can you see me today? Because I haven't been to the doctor in two years. Oh, I know I was the only one.

00:48:52

Speaker

You're not the only one. and And I'm not and trust me, I'm not glamorizing this by any means. In fact, I'm saying we need to practice what we preach. right Or is what I'm actually saying is that if we're talking to our patients about how to manage their blood pressure, how to manage their diabetes.

00:49:10

Speaker

and how to take care of their health and their prenatal care and et cetera, then we have to also be doing the same thing in terms of our own lifestyle changes that are going to benefit us so that we can then be more present, be more excited when we get to work, be more motivated when it comes to helping our patients and in our communities. And so that's what I would leave us with. Practice what we preach. Excellent.

00:49:40

Speaker

Now, whenever we have a guest on the Trauma Code, I like to give an opportunity to think about a cultural piece that doesn't have to do specifically with the topics we're discussing.

Recommendations for Resilience and Self-care

00:49:50

Speaker

But um any, again, while you have the the ear of New York City, any movies, books, music, performance, work of art, anything that you want to share with our audience that they might not be exposed to otherwise.

00:50:07

Speaker

Well, right now, I mean, I listen to a lot of podcasts. That's one of the things that I'm doing lately. And I was exposed to an author, um Robin Sharma. I was captivated by this author and and he was actually a a guest recently on um on a podcast called Feel Better, Live More. And so I would really encourage anybody to go ahead and listen to that.

00:50:34

Speaker

But moreover, as ah just a song that I thought was kind of appropriate for this particular talk that we had today, um it's called Superwoman by Alicia Keys. She's one of my favorite artists. And it was interesting. I just kind of went back on the words and what she was talking about in the song. And I felt like, you know, this is where I feel the most comfortable, right, is feeling like I can i can be a superwoman. I can do it all.

00:50:59

Speaker

But I don't have to. And the person that I also need to take care of is me. And so those are the two things that I would um leave us all with. And how how can our audience follow your work, Dr. Sophia?

00:51:14

Speaker

Well, I'm super excited. I have my own podcast, Dr. Sophia OBGYN. Embrace your body. Embrace yourself. You can find it on all of your podcasts medium. So whether that's Apple podcast, Spotify, YouTube, um they can find me at drsophiaobgyn.com.

00:51:34

Speaker

um And of course, if you want to come see me as a patient or OB, GY, and care, you can come see me at Symphony Medical in Yonkers in New York right now. And in all of my other little places that I'm at doing all kinds of wonderful things, I still do aesthetic medicine and I definitely have a big passion for menopause work. I think it's another place we have to have a whole other podcast on that. I'm adding that to the list of things we need to discuss with part two. And the trauma of menopause. um Though I'm so glad to hear so much more dialogue about this in mainstream media. But I do do a lot of that hormone balancing, et cetera, at um a place that's really near and dear to my heart called My Wellness Solutions in Harlem and the kind of work and the women and men that we do treat there. So those are some of the different places where you can find me.

00:52:29

Speaker

And again, thank you guys, both Simon and Cassandra for having me on your show today. It's absolutely our pleasure. We already look forward to part two, possibly part three.

00:52:41

Speaker

we've ever We've identified many topics to to circle back to. It's really a pleasure, Dr. Lubin, Dr. Sofia, to have you on with us. Why don't you go to Dr. Lubin anymore? I know, I know. Everybody, she delivered my baby, my second baby. um So I have a particular, boy yeah, do I have ah a very particular reverence for doctor for Dr. Sofia Lubin. And um I also just want to say in that,

00:53:09

Speaker

um that was in June 2020. That COVID baby and COVID baby, right. Right. And I remember, you know, it was actually Juneteenth was mostly the, like, I mostly labored on Juneteenth and gave birth very early on June 20. So there's ah some very particular things that I remember about that night. I think Alicia Keys actually, speaking of superwoman and John Legend, right. They were doing a versus and I was watching it.

00:53:36

Speaker

you know, on my laptop while I was, you know, contracting. he yes yes And for all the ways in which it was so difficult to be a patient or a provider in COVID, I do remember that it was such a quiet delivery room. There was like you, maybe a resident,

00:53:56

Speaker

And maybe one nurse, very few people were in and out of the room, obviously. And there was a, it it was serene. It was very peaceful. And I also remember after having given birth, like the next day, because they weren't trying to keep people in the hospital for too long.

00:54:11

Speaker

um during that time, even after childbirth, um you you came to see me and I remember crying and feeling so proud that another Haitian American doctor had delivered my baby. So I still have a picture of you holding my young son on my phone. Yeah, I mean, it's it's very, very dear to me. So you have a very significant place in my life. So I see you doctor. Thank you so much. i your doctor yes Thank you for joining us.

00:54:42

Speaker

Thank you.