Become a Creator today!Start creating today - Share your story with the world!

Start for free

00:00:00

00:00:01

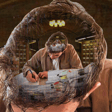

9 . Interview with a Catholic - Connor Wood

Here's my conversation with Connor Wood. Connor is, among other things, a writer and an adult convert from atheism to Catholicism.

We had a really interesting and wide ranging conversation, discussing the merits and failings of liberalism, ritual and religion, the story of Connor's conversion, and the question of how we can make sense of miracles in the light of modernity.

I hope you enjoy!

And please consider subscribing to my substack to support this podcast

The Sane & Miraculous substack

Notes

Transcript

Introduction and Episode Overview

00:00:01

Speaker

Hello, hello, hello. Welcome to the podcast. Today I have a very interesting guest for you, Connor Wood. We're going to be talking about Catholicism. We're going to be talking about the the the benefits and the limitations of liberalism and various details into anthropology, ritual and miracles.

Podcast Support and Engagement

00:00:28

Speaker

I'm going to say more about that in a moment and and kind of properly introduce the episode. But before I do that, I haven't figured out, let me just say, I haven't figured it out how to do this bit of the podcast, which is now necessary.

00:00:46

Speaker

ah telling this story backwards. So let me start by saying I am increasing the amount of time and energy I'm putting into the podcast. So starting from now, the frequency of episodes is going to go up and um and the amount of work that's going into the newsletter and it's the episodes is going up.

00:01:05

Speaker

so Well, that's not might be entirely true about individual episodes. I already put ah just obscene amount of work into editing. It's kind of crazy how much work it is. I might do a little less per episode, but it's going to be way more episodes. We're going to see how it goes. I might do about the same. It might not feel obscene now that I have.

00:01:25

Speaker

allocated more time for it anyway. So whatever, however much editing I do or don't do per episode, the the amount of output is going to increase. The quality is going to stay at least as good, if not better. And so this is taking more of my time and energy and I'm asking for your support. If you're enjoying the podcast, if it's valuable to you, there are a few ways you can support it. So this is the part, I don't know where to put this in the in an episode.

00:01:51

Speaker

Okay, so I have to, you know, the structure of an episode where I'm talking with someone is the beginning. I'm going to introduce the person and then there's going to be the conversation. And that's the end. I don't really know where to put this kind of, you know, how do you help pitch in these episodes? so I'm still figuring it out, but as you can tell right now where I'm putting it is almost at the beginning with just enough before it of explaining what this episode is going to be about that you don't just feel.

00:02:20

Speaker

immediately pitched. Anyway, hello. So here are the ways that you can support this podcast. Number one absolute gold standard amazing way of supporting is subscribe as a paid subscriber on the sub stack. It's currently $5 a month.

00:02:36

Speaker

very ah reasonable and affordable, I would say. And for that subscription, not only do you get the good feeling in your heart of supporting the podcast, you also get some extra content, ah including today, there's going to be a little bit of a debrief reflection on this interview, which is for subscribers only. And that's one of the, that's going to be Comment to anytime I interview someone I'm gonna do a little reflection which is for subscribers only So if you want to hear my behind the scenes thoughts about how this conversation went What I wish I'd said and all that kind of stuff if you subscribe you will get that information today um So that's one way you can support it if you are already doing that. Thank you so much or if you are a Don't want to do that yet. Other ways you can support is whatever podcast player you're using is going to have some kind of rating thing. Or if you go on iTunes and give the, uh, give the podcast a five star review. That's super helpful. Uh, has to be five stars because of the way the algorithms work.

00:03:38

Speaker

It's just incredible star rating inflation in the world. And so five stars is the thing that will make a difference. And a review will also make a difference. So if you want to do that, that's super helpful. And finally, I believe at this point, ah sharing the podcast on social media, sharing with your friends, if you if you you know know someone that would enjoy it, all of that super helpful. So anyway, that's the end of my pitch. Thanks for any way that you choose to but Okay. So now the conversation you're about to listen to with Connor, what's it about? So there were a few different things going on earlier this year, kind of the summer around Christianity. There's like an up swelling of Christianity, right? I don't know if anyone's noticed this, but like it's, it's kind of more, and even just recently, like

00:04:28

Speaker

Russell Brandt just kind of like publicly converted. Ayaan Hirsi Ali wrote a post in July. This was kind of one of the big impetuses for this, saying we need to be Christians, like it's going to be good ah for for Western society, right? ah And Jordan Peterson, it's just like, there's a lot of there's a lot of people talking about Christianity and kind of in a new way.

Miracles in Religion and Modernism

00:04:50

Speaker

And the thing for me that has always been just a deal breaker just like nope Christianity doesn't work as a religion unfortunately uh the miracles the uh and you know there are several but let's just say the resurrection

00:05:08

Speaker

It's kind of like the main one, the most important one. And personally, I have not really found a way to reconcile. What's more fair to say is like I haven't had reason enough to try and find a way to reconcile the the account of the resurrection and you know and and a kind of modernist understanding of of reality and of nature. And it just hasn't...

00:05:39

Speaker

the The case has not been compellingly made that I should try and do that. And given that, it's like, well, why would I? like it's it's you know There are any number of accounts of miracles in any number of other traditions, which I don't try and reconcile with modern. you know In Buddhism, for example, there are stories about the Buddha like emitting flames from his arms or ah splitting his body into multiple forms and ah and being in multiple places at the same time.

00:06:08

Speaker

I don't think that happened. Don't think it happened. Love Buddhism. Don't think that stuff happened. But with Christianity, the thing about Buddhism is the the point of Buddhism is not the miracles that the Buddha did or didn't perform.

00:06:20

Speaker

Those are not central. What's central is the teaching of the Buddha, which is which is the Four Noble Truths and you know everything that came out of that. But with Christianity, the miracle is central. The resurrection is central to Christianity. As Connor says in this episode, he quoting Paul, if the resurrection didn't happen, this is all a waste of time. Something like that.

00:06:45

Speaker

he I think he paraphrased Paul. I'm paraphrasing him paraphrasing Paul. Anyway, this is central to Christianity, this belief in the uniquely, mirac and both in the miracle and the resurrection, but also in the unique status of Jesus Christ as as uniquely the Son of God.

00:07:05

Speaker

right And it's just always been implausible to me. And I wanted to find somebody who is intelligent and thoughtful and understands the modernist worldview um and kind of, you know, has integrated those insights. Cause there's a, there's a kind of person who believes this stuff, who just doesn't really understand his not, you know, in, in developmental terms has not kind of integrated.

00:07:32

Speaker

modern thinking. And so just doesn't really understand why there is even a problem here about the resurrection or about any of the miracles and just says, no, well, God did it. That's fine. I don't just believe that. Okay. I'm not interested in talking to that person. It's not going to be intellectually useful because they're just not really working to integrate.

00:07:54

Speaker

they're eliding the problem by not and by not having integrated the modernist worldview, right? And so just to lay it out in case it's not crystal clear, the modernist worldview says that like nature is this physical process that's happening and we understand through science and through observation and the miracles are excluded from the modernist world modernist worldview definitionally.

00:08:21

Speaker

right A miracle is something which is not happening through the process of normal operations of nature. And what the modernist worldview says is there is only what's happening through the normal processes of nature. And so there's no way for something to happen that is distinct than that. Now, I think the modernist worldview you is missing something, but We have to go through modernism and we have to integrate modernism before we can get to the next thing. So this is turning into a long and true. But this is the problem, right? There's modernism and then this is the count of the miracles. How do you reconcile those two things? Well, one way you can do it, which is partly how I do it, is to say there aren't those miracles aren't real. I don't think modernism is the whole picture, but I don't think that the the part of the picture that modernism misses is miracles.

00:09:15

Speaker

don't think that's what modernism gets wrong. I actually think that modernism is right that there are no miracles, not in the sense of events happening outside of the processes of nature. I might be wrong about that, but that's where I live today. So you have to integrate it somehow. And I wanted somebody who had worked to integrate it to talk with on the podcast and a mutual friend of of mine and Connor's suggested Connor. I was kind of like talking to people I know that were ah Christian, and he said, oh, you should talk to Connor. And I'm so glad I did. Connor Wood is amongst other things, a writer on Substack. ah His Substack is Culture Uncurled. There are links to some of his articles in the description of this podcast.

00:10:03

Speaker

I highly recommend you check it out. Really great reads and Connor more than fit the bill of who I was looking for for this conversation. I, you know, I was looking for this kind of abstract idea, like ah a Catholic who was ah informed by modernism, but I got a real human being with amazing insights of his own. And so that was super satisfying.

00:10:26

Speaker

super interesting background, super thoughtful. we We cover a lot of ground. As I said earlier, we talk about liberalism. We talk about we talk about some ideas from anthropology, different religious traditions, Connor's conversion story, which is super interesting. Like he was not raised Catholic, which I think also makes his story more interesting, but he converted later in life, all kinds of things. Had a great time talking with Connor. Now we do.

00:10:53

Speaker

talk about the miracles and specifically the resurrection. And I, you know, I challenge him on this point that that I'm raising. I will leave it to you to decide whether his answer satisfy, he has an answer, whether his answer is satisfying for you in terms of, in terms of the resolution of this seeming conflict. But regardless of what you decide about that particular question, I think it's super interesting conversation and hope you enjoy.

00:11:39

Speaker

In a way, you can think about the cognitive science of religion or just even more broadly, the that the scientific study of religion to be the study of the negative space in modern liberalism. OK.

Science, Religion, and Human Nature

00:11:56

Speaker

Right? Like everything that seems to not make sense about how humans behave, if you take a kind of Lockean, rational, autonomous view of human nature as your framework, that's what I study. and And so that leads you naturally to questions of human nature, because we live in a liberal society, in the United States is the paradigmatic liberal political entity, right? Like we are the standard bearer.

00:12:21

Speaker

of modern liberalism. Currently. Currently, yeah, for better and for worse. yeah And um ah we were founded that way. that's the that you know and And that's the waters we swim in. And so the more deeply I delve into this line of study, the more it occurred to me that we might be on some pretty shaky ground in terms of our our our our premises.

00:12:47

Speaker

Because there is this black there is this negative space. There's a whole lot about human nature that is completely unaccounted for and ah um the the liberal anthropology that we've inherited from the enlightenment um from the American founding fathers from the whole modern turn. And ah so that's where that's that's where I ended up. maybe I think this is this is a really fascinating time to be alive, to be studying this sort of thing, because we can all sense that liberalism is undergoing a crisis.

00:13:27

Speaker

And i would I would say that part of that crisis is epistemological and anthropological. It's just that that the data just don't support some of the basic premises about how humans act and and what we are what we are like. um For example, yeah, ritual is an example, right? where Where ritual only works if you accept some form of authority to determine the form of the ritual.

00:13:56

Speaker

Right. And so yeah there's a there's a kind of a teleological structure to it from the get go. That if you are, I love the example of a Jewish Seder, because it's probably just one of the um it's one of the most complete examples of a human ritual I can I can I can think of. And and then they're also fun. um So I don't know if you know a Seder, the Passover ritual. Remind me. So it's it's, it's a dinner.

00:14:25

Speaker

And you gather in somebody's house, maybe a rabbi's house, but maybe not. And you um you do a series of readings and eating specific foods, not not all of which I'm going to remember, but like bitter herbs and red wine and excuse me, unleavened bread and things like that. and But you have to do it in a set order and you do the same readings. And it's the story of the Jew of the Israelites um passage out of Egypt. Right.

00:14:52

Speaker

right And so you you yeah you ask questions, there's got to be children there, so you can ask them questions like, why did we do this? Why do we say this? What night what makes tonight different from all other nights? well because we and And there's a ritualized response. right So the whole thing is templated. And it's not practical.

00:15:10

Speaker

right it's not ah It's not a normal dinner and that the the function of it is not just to nourish your body. In fact, I've been to maybe half a dozen satyrs. I don't think I've ever come away feeling like full, really. you know' That's not the point. The point is to go through this.

00:15:26

Speaker

um the structure, which is templated by a tradition that you cannot change, basically. I mean, you can, you can mess with it, especially, especially in modern America, people come up with all kinds of different ways to change the seder. But generally, you know, the point is a a ritual like that is structured by some form of collective intentionality that transcends the individual and so is not amenable to rational decision making.

00:15:55

Speaker

you know in ah in a ah an empiricist sense. You can't say to yourself, well, I'm only going to take part in this ritual if I can determine based on my own reason that it makes sense, that it's practical, right that it's it's ah it's a and good thing to do, because that line of reasoning will terminate nowhere. it's It's not the appropriate line of reasoning for that. You have to basically say, either I accept the authority of this culture, this religion, this tradition, or I don't. And if you do, then you do it. And if you don't, then you don't. And so there's a there's a kind of a priori um decision about what authority to trust. And that's the same for almost any sort of, you know, ritual or or or common tradition. And um it's not well accounted for. And I think a lot of the

00:16:51

Speaker

at least the kind of more vulgar versions of the Enlightenment anthropology that we're all heirs to, where, like, for example, Kant says, um sapere aude, right? dare to Basically, dare to use your own reason, you know. And the the motto for the Royal Society is nulias in verbe.

00:17:13

Speaker

um roughly, like, don't take anybody's word for it. Find out yourself, you know, and that's the kind of like macho, you know, like, like yeah call to arms that the whole modern world is based on is I figured it out for yourself, don't trust authority, right? Well, but the, the the modern human sciences, if I modern, I really mean 21st century, this is like, you know, the past couple decades have made massive advances in understanding how our brains work in a social way. And it turns out they are almost literally designed for picking up on cultural authority and and replicating it, basically. That's that's that's what differentiates us almost better than anything else from chimpanzees.

00:17:56

Speaker

to play the other side of that, ah the the Enlightenment people would say, exactly. That's why we had to write these books. That's why we had to have these mottos. That's why we had to make this claim because left to our own devices, human beings will be trapped in these kind of like, you know, these cultural patterns that that are, if not arbitrary, then, you know, kind of not open to evolution and not open to to kind of the rapid Input of new information i mean you like the thing about modernity is they did get a lot of things right like there is a baby in that bath water yeah one hundred percent. um I love plumbing right you know ah well of course which isn't a completely modern mission the roman said plumbing but.

00:18:44

Speaker

We have better plumbing. Yeah, yeah but we have, uh, anesthetics for dentistry. That's like high up on my list. I love that. Yeah. And we have, and we have antibiotics and we have public health, ah you know, knowledge about, um, pathogens and things like that. Um, doesn't always work perfectly as we just experienced, but, um, you know, it's better than, it's better than having typhus like breakout in your cities every couple of years, like it used to. So yeah, there's a lot of, there's a lot of good and, um,

00:19:15

Speaker

that comes out of that ah expansion, I wouldn't have any expansion, like explosion of openness to new information being sort of injected into our and our societies, our ways of seeing the world and so forth. But I guess two things about that. The first is that humans are already quite good at that. We have what's called cumulative cultural evolution.

00:19:45

Speaker

And our ancestors um in the human lineage, for example, for example Neanderthal, homo Neanderthalis, seem to have some of the same cognitive features that we do that are unusual. um One of them is called over imitation. And that's that's very closely related to what I was just talking about in terms of the authority that allows rituals to kind of propagate across generations is that humans seem to have a motivation, a motivational structure that pushes us to replicate non instrumental action sequences when they're performed by somebody who we trust and

00:20:30

Speaker

What I mean is, you know if you see somebody pop open a pop can, a soda can or whatever, and and drink from it, it's like, well, that's that's kind of an instrumental thing. you know There's a physical causal relationship between pushing down the tab and getting the can open, right? Okay, whatever. you know Once you figure that out, you don't need to be ah fastidious about copying exactly how somebody does that. But when it comes to a ritual, like a Seder or like crossing yourself coming into a church, there is there is no there's no physical causal relationship between what what you've just done and any practical outcome.

00:21:01

Speaker

and when the So when the human brain sees somebody do something like that, it tags it with a salience marker, um roughly. Experiments show that when people that when people see non-instrumental action sequences that others are performing, they they experience them as more salient than practical action sequences. Your brain basically says, hey, pay attention. This is important. And then we're motivated to repeat the whole sequence you know, top top to bottom. um Whereas chimpanzees, who are very closely, you know, they're our closest living relative, and in many ways, they're, they are like uncanny valley close to us, you know, if you go to a go to a zoo, and it's just like, it's, it's almost creepy how similar their hands are, some of the facial expressions, right? But they don't do this, they just don't that it's like, they, they will copy things only to get

00:21:58

Speaker

ah a goal accomplished. They want the treat that's in the box, right? They don't want to do all kinds of weird ritualistic things to the box to get the the treat out. But human humans of all kinds of backgrounds all around the world do. If you show ah if you show a treat a box with a treat in it and you show a certain way to open it where you're tapping on it three times and you're doing all these things that you don't need to do, as soon as it's apparent that you don't need to do those things, chimpanzees skip all that crap and go right for the treat. They just pull open the drawer.

00:22:28

Speaker

yum you know humans by and large keep doing the the the unnecessary steps within within that experiment. It's a pretty famous experiment that's been repeated in all kinds of ways. There is something about humans, the motivational structures of our social cognition, of our social reasoning that make us want to repeat things that that we can't figure out necessarily the practical goal of. So why do we do that?

00:22:56

Speaker

Well, one answer is because a lot of technologies require basically bracketing our questions about what the point is when we're in the learning stage. The example that's often used is carving out a canoe. This is an example from Joe Henrich at Harvard who is an influential figure in my field. um ah Carving out a canoe is super hard and complex and it requires a lot of steps.

00:23:25

Speaker

And the steps, you know, I'm out of ah out of a log, right? You know, like something, right. And um and the steps that you start with, if you don't if you've never done it before, and you've never seen anybody carve a continue out of a log, you might not really get why you're doing those first steps. And so it makes sense to if you're if you want to learn how to a technological skill, it makes sense to just copy what you see people doing, even if you don't really know why it's there, why they're doing it. Right. And that's, that's ah important. That is a key mechanism for the transmission of know-how that makes makes human life possible. right i mean that was my first so when you When you were describing this phenomenon, and I thought of the you know the cargo cults at the end of the Second World War. ah have you come of Do you know that story? Yeah, yeah in Polynesia. yeah Yeah, exactly. So just briefly, during the Second World War on these islands, the US military had these kind of established these bases on these islands, and they would build landing strips for their planes, and the planes would fly in, they would bring all this cargo, and the local people would like these cargo would be like this amazing stuff, like this great clothes, food, whatever other supplies. And, and so the local people were like, these planes are really good news. And then war ended, all the planes went back to the US and the local people tried to recreate the process they built,

00:24:42

Speaker

landing strips, they built air control or air traffic control towers, they built like little ah headsets out of ah bamboo and stuff like this, and they would try and summon the planes, they would reenact the, you know, the behaviors that they'd seen the the the US s military doing.

00:24:57

Speaker

to try and summon these planes. Obviously, it doesn't work, but that just reminds me of that. and And yeah, the thought I had as you were saying is like, well, if you don't understand why someone's doing something, doing it is a way to try and figure out why they're doing it. So you don't understand why someone's crossing themselves when they walk into a church. Well, if I do that, maybe I'll learn something. What's interesting is and i that would explain, I think that would explain like repeating rituals that are completely non-utilitarian, like you said, like, you know, the satyr or the going into the church. But the thing with the box where, like, there's a bunch of rituals about opening the box and then you just open the box, I would think that once you'd figured out, wait a second, it seems like the part of this ritual that actually gets the box open is the part where I lift the lid. Like, what happens if I skip this step? Oh, I still get the box open. All right, forget about that step. So there's something like,

00:25:51

Speaker

There's something else interesting in there, right? Like that's the people are maintaining the rituals even when the practical part becomes clear. Studies show this, that when the for practical action, for fraction sequences are actually practical, the adherence to the all of the steps declines over time as people figure it out, right? It does do that. Okay, gotcha.

00:26:16

Speaker

Okay. where whereas Whereas for um sequences that are just it just purely conventional, right? They don't. And the motivations, the study that lots there's a lot of lot of people who study this stuff, mostly in developmental psychology. So you know they'll do do these studies with kids, but it's not just kids. In fact, the tendency to overemitate continues to increase over over childhood into adulthood and peaks in adulthood. know Adults are the most conformist in some ways.

00:26:45

Speaker

um maybe because you over over the course of childhood, you learn that it often pays off to just do what you see and bracket the question of why until later. But the the motivations for the for following the conventional patterns, you know to which just doing for fo for repeating, mimicking a sequence that just is purely conventional seems to be um basically affiliative. It's a way of showing that you belong.

00:27:11

Speaker

the group, right? and Because if you walk into church, and you don't, you Catholic Church, whatever, and you don't cross yourself, and you don't kneel when other people kneel, you're basically saying like, I'm here, but I don't, um I don't buy it, like, I'm not part of this, right? And if you go to a seder, and you just sit there with your arms crossed, you know, same way, it's like, that's your, you're clearly signaling that this is not a convention that you find, ah ah to meet it's not a group that you want to affiliate with right So it's like, why are you there? you know And so the groups that we spend time with are the ones where we say, OK, I trust these people. I want to belong to them. I've got something invested in these relationships. So I will do the weird things that they do, um basically, in order to to signal that commitment. And so this is this is something that actually precedes human Homo sapiens. this And we can tell this because there are tools

00:28:07

Speaker

that we've uncovered going all the way back to, um, I want to say about 1.2 million years ago, um, called, uh, hand, uh, the Aculian age, uh, these hand axes where you you you carve a piece of stone into basically a teardrop shape and you use it for carving, right? You carve out, carve meat off of hide and bone and things like that. Right. It's an all purpose tool.

00:28:37

Speaker

And the as as yeah protohumans developed, you see a ah kind of shift in this stone technology. So first of all, it's kind of cool that there's been technology for longer than there's been homo sapiens, right?

00:28:54

Speaker

There's been fire for longer than there's been homo sapiens. It looks like we probably had the ability to control fire for at least 400,000 years, I think. there's The estimates vary. But that's that's longer ago than we think that modern homo sapiens develop. right So we're we're inheriting a lot of weird, interesting stuff here. But when as you go through the archeological archaeological record, at some point, you come to this point where the hand axes are formed in a way that you could not do without some form of over imitation, right? you're You're learning and closely mimicking a model, a teacher, right? And you're you're making the the tools more symmetrical than they need to be practically. So you're you're you're seeing you're seeing basic basically conventionality developing.

00:29:39

Speaker

where you're making them more beautiful than they need to be your flaking it in ways where if you just picked up a piece of rock on your own and tried to start doing it, you would never do it. So you need some sort of cultural learning. But then this technology, the Akulian hand axe industry remains almost completely static.

00:29:59

Speaker

for something like 700,000 or 800,000 years. That's crazy. right so that's that's what That's what you were just talking about. That's what it looks like to have no openness to change. right right there's These proto that protohumans were so good at... I forget which species exactly we're talking about here. I think it continued into Homo neanderthalis.

00:30:25

Speaker

um We're so good over imitation that they could not really develop what we now call cumulative cultural evolution which is a kind of a ratcheting balance between over imitation and preservation of cultural and conventional practices and.

00:30:41

Speaker

progressive development of those practices, especially in the technological development. And Homo Sapiens seem to have hit a balance there long before the Enlightenment, you know, when we're talking 150,000 years ago, um where we where we're able to build ah build progressively on technology because well well we'll come to master ah you know, will as individuals will come to master the teaching that we've received, and then know it well enough to know where we might be able to innovate, right, where we're going to be able to experiment, isn and and then pass down that new development to the next generation. So, so this is this is, that's one answer to what you what you asked back there about, well, you know, how how would over imitation, um not

00:31:27

Speaker

I forget exactly how you phrased it, but but how would that not lead us to be sort of static and stagnant? And then the other one would be the other answer to that broad question, the but the challenge you brought to this research on over imitation is to say that um essentially my way of looking at it is that the the the hard, um maybe even like straw man version of enlightenment anthropology. I wouldn't say that necessarily any one person holds, but that I would say is ambient in our culture, is that we're is is essentially pushing us to become more like chimpanzees. okay Literally, right? It wants us, chimpanzees figure stuff out on their own. They don't trust authority. They don't copy

00:32:14

Speaker

they don't They don't just do what somebody else tells them. they want They want to get what's right there in front of them right there and and and and in a way that makes sense. So there's a real way. and so There's actually something anthropologically regressive about um the broad version of liberal anthropology that we all seem to be swimming in. Okay there ah there's a lot there's a lot of pieces when you were saying like the 700 800 000 years I had the thought like oh man if they'd only like kept innovating a little earlier where would we be today right but um I think there's like ah almost an anthropic principle working there where it's like well they weren't going to because they weren't going to Or if they had, then we would just be having this conversation, you know, 500,000 years earlier, but we wouldn't know the difference. Like what difference does it make? Anyway, it's kind of a weird philosophical point. There's two threads that I want to pursue with you on this call.

Liberalism and Cultural Exploration

00:33:06

Speaker

And this is super interesting. Like everything you just said, I had no idea what we were going to be talking about. it's Your background is very interesting. And then I think we're kind of coming into these two.

00:33:14

Speaker

threads. And one is, and do you know, they're related. And I think one is from what I've read of yours, and also the conversations with our mutual friends and moments where he's relayed something that you have said, I get the impression that you have some kind of skepticism about What you're saying skepticpism about liberalism even more like not just like kind of the progressive like extreme kind of version of. ah I don don't know if you wouldn't even call that liberalism because i think it's kind of highly illiberal but like like it's one version of post liberalism post liberalism sure it's one version of like a left post liberalism. Yeah, right. And so, so there's the kind of skepticism of that, which I'm i'm interested to to explore. And then I just want to name the other thread, like the way you're talking about ritual right now is in this very kind of anthropological scientific way that's, you know, your training and your background. But I think that you also have a kind of a mystical

00:34:13

Speaker

relationship with these rituals. I don't know if you if you would describe it as that, but they are at the very least a ah spiritual relationship with certain rituals that's beyond the kind of purely, well, isn't that interesting what human beings do? um And, you know, because I think to kind of give some context for how we ended up on this call together, is I was looking to talk to somebody who happily identifies as a Christian, including the belief in the miracles, specifically the resurrection. So I just kind of want to bring that thread in here and maybe kind of start with, and we can get into the the Christian stuff, but with liberalism kind of wanting to reduce us to this kind of pre-cultural, like that's what I hear you saying. It's like, like that by rejecting cultural authority,

00:35:01

Speaker

then what were then we are no better than chimpanzees. And we're just going to go back to this kind of each each person figures everything out for themselves, just does does things however they want to do, and um and and kind of follows their own impulses. And to me, I do think that there is that in the atmosphere.

00:35:22

Speaker

And that it feels related to me to this experience of ingratitude that I notice in, in the progressive left of this kind of this like aggressive rejection of everything that, that led them to where they are, right? Like the, the kind of God, you know, and especially intensity, these kinds of elite.

00:35:43

Speaker

I leave folks who are doing this and there was something you know i read in one of your articles that ah that actually really moved me um in your essay about your mom which is really great now i'll link these in the show notes tonight i. i ah I really enjoyed that article and one thing that really moved me in that actually so kind of surprisingly was this kind of moment where you where you kind of describe this patriotism that's this kind of like Eclectic, I don't know how I've described it but this patriotism that like includes like the European culture includes the Native American culture includes the African American culture and kind of sees all of these as these kind of foundational pieces of the American puzzle and

00:36:29

Speaker

that i I just found beautiful and kind of moving and and there was like, and you know, I'm a, I'm a transplant. Like I didn't grow up here. And so there's a way that like, I don't have quite the privilege to like sneer at America the way a lot of my contemporaries do because like, you know, it's not everybody's favorite past. Yeah, exactly. But it's not my, I do about England. I will sneer all day long. I'm very cranky about England. But in America, there's just a little bit of like, you know, I'm a guest here to a certain extent, and I want to be a little bit respectful.

00:36:57

Speaker

And I think that allows my, I mean there's many reasons why this is true, but I think that allows my heart to stay open to the country in a way that I think a lot of educated modern Americans, ah especially on the left, or specifically on the left, have lost their sense of what's extraordinary about this country. But to me,

00:37:17

Speaker

part of what's extraordinary about this country is the liberalism. Like, I love the liberalism. For me, the thing that is creepy is the illiberalism which is rising now on both sides of the spectrum. Because what I hear you saying is like human nature just works better if you acknowledge these things and that we actually, it's part of our gift to have this kind of cultural learning over time and accumulation and and that we want to keep that, which I completely agree with. And I do think that there's something about liberalism that that is about a kind of a superhuman ideal. And so it's dangerous because it's about a superhuman ideal and it's dangerous for it to kind of demand that we live up to a superhuman ideal. But I think it's also that there's a that it's inspiring and it's valuable to have something that's like, it's not up to me to decide how anybody else lives.

00:38:14

Speaker

And that there's something, and you know, maybe there's just some kind of anti-authoritarian kind of bent to that, but like that kind of fundamental, like, people should be left to do what they want. Partly because, it's funny, that I just learned that letting a thousand blossoms bloom, I don't know, do you know the origin of that, let a thousand flowers bloom? Do you know where that expression came from? No, I don't think I do, no.

00:38:36

Speaker

it's It sounds like this kind of just like, of course, it's some liberal, right? Like it's just like such a liberal idea. It's Mao Zedong. That comes from the Cultural Revolution, I know, which is so wild. Anyway, whatever. But regardless of the artist, let a thousand flowers bloom and then kill them all. sound Exactly, right? but But let a thousand flowers bloom and and because we'll learn things.

00:38:59

Speaker

right It's great that like you know and the hippies went and did these communes because we figured out like maybe that's not a good idea. right like It's good. Why do we have to keep figuring it out, though? ah Because we do right in the same way. right like why do we have to keep you know Why do we have to keep coming to the brink of authoritarianism and then only to kind of scramble and be like, no, no, no, or even go into it and say, I have to fight back? Because you know because we're flawed. and we do And I think we have to keep figuring these things out. and i think we have to We have to let novelty blossom. For me, like there's this deep ethics of novelty and diversity and the idea that what's good is a lot of different things happening, a lot of difference, because in a lot of difference, it allows us to explore the largest possible landscape of humanity and of, you know, reality and any unnecessary reduction. There's some kinds of difference, which are bad, but I always want to be very cautious about

00:39:58

Speaker

ah too aggressively trying to reduce difference because we don't know. We don't know what spaces there are to discover, right? So anyway, that's a long kind of response to some of what you've said so far. Yeah. Yeah. Well, there's a lot there. Yeah. I mean, I am a Christian. i'm I'm a Catholic actually. And that was not true before I started studying all the stuff that I was just talking about. and There is a there is a real way in which I think coming into a more accurate and scientifically informed picture of human nature led me to to revisit what I think is the foundational anthropology for for our culture, which is the Christian one. In my estimation, that it it ended up being a lot a lot more compatible with with what I had learned from the sciences than the the the liberal modern one. Having said that,

00:40:52

Speaker

I agree, there's a lot of good and and you know like i said in in the role of modernity. and And you coming from the UK, there is something there's something really precious in what they call like the Anglo-American political heritage that I really would like to see us treasure more and and and recommit to to passing down and to and to convincing people. right like I think one of the things we're experiencing, and you mentioned kind of the the some of the excesses of the extreme left, which I'm very familiar with, because I was raised in the extreme left. And I went to, I've spent most of my adult life in research universities, you know, where where it's just crazy. It's like literally crazy. and And I'm very glad to be out of it now. Because I'm not impression professionally in academia anymore. And I don't know how I could be if if it were

00:41:47

Speaker

if it weren't in some sort like you know some sort of a weird like Catholic school or what you know but but like modern secular prestige academy, like they wouldn't hire me at all for the last few years. if you've been If you've checked my demographic boxes, you literally are not going to get hired almost anywhere. There's exceptions, but not going to happen for the most part. yeah i could just It used to drive me crazy. I was right up against it. you know The Boston University School of Theology, where I hung out a lot, is probably one of the most extreme academic environments in the country in terms of the progressivism, that sort of thing. So I've been face to face with that. And I know what you're talking about. There's something really important about liberalism as against that kind of left extremism that I think we we need to we do need to preserve that does come from the Anglo-American tradition of respect for individual rights, a kind of accountability in government and expectation of participation and of competent participation.

00:42:46

Speaker

right, for the citizenry in in ah in a government or in a polity of respect for for property rights. debt and that's not That's not one that I used to care that much about, but but you know and now I see it's like, well, look, every time we try and do something else, you know look at Venezuela right now, you know where you where where property rights become non-inviolable, you just cannot stabilize an economy. you have to i mean This is one area where Locke was right, is that you have to have something invested in the outcome of improving property, of doing something with with what you own, if you want people to actually produce value with it. I wouldn't say I completely buy into his idea that ownership equals possession plus improvement right um with property, but that's exactly what he said. In general, I think there's something important to that combination that that really went its furthest in the Anglo-American sphere

00:43:35

Speaker

But I also think, you know, you mentioned the patriotism angle, and I do think that there's something about that world, that that system that has always produced a higher number of people than is healthy, who just don't feel any connection or responsibility to the the polity.

00:43:57

Speaker

even in 100 years ago, George Orwell was writing about how the English intellectuals in in the interwar period were were but almost completely opposed to everything English. I mean, it was the if you it was just like today, right? It's a late empire um coming probably to the end of its time as ah as the global hegemon filled with intellectuals who hated the country and who and who gained social status by expressing how much they hated the country. It's like we've we've seen this show before and there's something about this particular way of setting things up that we have in in the UK and the United States and Canada and Australia and the Anglosphere in general that just seems to give a greater leeway to this type of person

00:44:40

Speaker

who's who's intellectual and um gain social status by signaling their lack of commitment and their lack of need, ah their lack of dependence on the broader social like organism. it's That's unhealthy. So there's there's there are lots of bugs to work out. And i think that I think that something like a humble rooted patriotism is really what we need to work out those bugs. You need need to just love the land and the people And that doesn't mean blood and soil nationalism is the kind that you you find on the the extreme right wing, you know where it's all about ethnicity and things like that. it's It's really just like when you love America, you need to love all the people. and and that And that includes descendants of slaves and descendants of European settlers and American Indians and more recent immigrants and everything. There is a story going on here and you either need to accept the whole thing or you need to reject the whole thing. And I think there's a kind of humility and and grace that comes with

00:45:38

Speaker

you know, just like learning the folk stories. I think that's something that could really be helpful for people is, is recovering the fact that we actually have folk traditions in this country. We have, I don't know if you've ever come across the rare rabbit stories. Yeah. When I was a kid. Yeah. Yeah. Like that's great stuff. It just roots you in, it roots you in the land and the people and it roots you in Africa and Europe, right. Um, and gives you something, um, to tether to and,

00:46:06

Speaker

anchors you. And so i to to know those stories, to know the Paul Bunyan stories, the Pecos Bill stories, just all the kind of stuff I read when I was a kid, and i but I think a lot of people now are not reading. you know In short, you have to have a folk culture to have the kind of loyalty that I'm talking about.

00:46:21

Speaker

So here's something that's interesting, because in america you know what's what's interesting about America right is that it is this country a of immigrants, like more so than maybe anywhere else in the world. right Is that fair to say? I think so. By percentage, it might not. By percentage, it might be Canada or or Australia at this point. but But yeah, generally. Okay, there are many, many different cultures represented here. And in the UK, that's also true, I think, to a less... degree you know One of the things though that's really interesting about the UK is like, just these thousands of pockets of microcultures that have been there for like, just like centuries. the In the accents are so like, you move from one town to the next and you can hear oh yeah the different accents, right? In America, you don't have that, right?

00:47:01

Speaker

Why I'm saying this is like you know I grew up with Briar Rabbit right like and you know and European folk stories right and Beatrice Potter and and um ah she's great yeah and I didn't know that Briar Rabbit isn't like ah in the cultural lineage of England directly. But it's still, there's a tension, I guess, in me of appreciating the patriotism and also a kind of globalist sensibility that's like, well, I love all the cultures. Why not just take the good from all of the cultures and celebrate them in this kind of cosmopolitan thing? I guess for me, the part where I really resonate with you is like the the political project of the democratic US and of the UK and that

00:47:47

Speaker

being this kind of source of of patriotism and that being the source of like, it's almost like, well, the thing that I love about these countries is so global is is the is the not being exclusively about this kind of lineage and this culture, but of actually including the world. I think there are some problems with that i agree i I find myself, my wife and I like to talk about the fact that it seems it seems to both of us that were we're anywhere people who would like to be somewhere people, who feel called to be somewhere people. you know my My reference frame is very global. I've i've lived in Germany and South Korea. um I've traveled to all the inhabited continents except for Australia.

00:48:34

Speaker

Most of my friends are people who are very, you know, well educated and have traveled a lot. And it's just at Oxford for a conference last week. And that's like a, you know, it's just that that's, that's, which is great, but I've never been there before. Beautiful city. And, um, yeah, that's kind of my reference frame as an adult, you know? Um, but there's a way in which having that kind of globalist mentality where it's like, like, like you said, let's, take why not take the best from all cultures that is necessarily, I think,

00:49:02

Speaker

or or always at least in strong risk of just being consumerist, right? Like taking this consumerist attitude to the whole world. And of course it makes sense for us English and American people to feel that way because we've been in charge of the world for the past 200 years. We've been the global... The future historians will look back on the 1800s and the 1900s and the early 21st century as being one long Anglo-American empire.

00:49:29

Speaker

where it's like we've ruled the seas, you know, and and there's a specific meaning to that. I mean, it's like our first, the British Navy and then almost seamless transition. The American Navy have been the ones that have made it possible for world trade to to spread around the world so easily because you don't have pirates to, you know, and and you can see that it's breaking down now because all of a sudden we're getting pirates again. You know, it's like the British, the British and the Americans kept pirates down to the point where we could develop this global system worldwide trade because pirates introduce and other kinds of instability on the seas introduce all kinds of transaction costs that make it not worth it to do to do globalized trade. But we've made it possible for that to happen. And so we're kind of the center of this globalized world. And so for us, it feels like the whole world is sort of our place. you know it's it's like It's all relevant to us.

00:50:17

Speaker

it's all part of our environment, whereas if you live in Argentina or someplace that's never been on hegemon, it's like, you know, the whole world is not quite the same way, your responsibility. um So there's an imperial attitude, I think, that's inextricable from that globalized expectation of being able to take all of the good from all the world's cultures, but leave the bad. And then there's also the question of what is the good and the bad? what What's good to a Brit? It might not be what's good to a Moroccan. Actually, it won't be, you know? And so if you go to Morocco and you only take the good, then then well, that might mean that you very well leave behind exactly what the Moroccan most loves about this country. ah people right And so so there's there's something, you know, radically intention there.

00:51:08

Speaker

and i And overall, I think that empire is not great for the

Historical Context of Empires

00:51:13

Speaker

empire builders themselves. That's my main it's not I'm not so much of a bleeding heart when it's like, like, I don't know. We were like, Oh, the British Empire was so terrible. It was exploitation is everything. Well, it's like you go back and you look at history. It's the reason the British Empire expanded so rapidly in Africa was because they kept they kept finding that they they the next tribe over was the one that was selling slaves and they were trying to eradicate slavery. And so there was this strong pressure from educated women back home in England. Does this sound familiar? To do good and and fixed and and end slavery. And so the military kept pushing further and further into the African interior, finding the fight finding the the the the kingdoms and tribes that were just the centers for the slave trade on the interior of Africa. and until

00:52:02

Speaker

they ended up controlling half of it. it's I'm not saying it was all good. I'm not saying there wasn't a lot of selfishness involved, but there are, there's a lot of, and I think moral ambivalence and ambiguity to the British and the American empires. We've done a lot of good as well as a lot of bad, but I don't think that being Imperial hegemon is good for us in some important way. Like you need some sort of humility and you need to, I think an important step in just growing up, becoming a mature,

00:52:31

Speaker

member of homo ah Homo sapiens is learning that you can't be everywhere all the time. It's just saying, but look, i like I have to delimit my options.

00:52:43

Speaker

And there's all kinds of ways that happens. You choose a career, and and and you you have sunk costs. it's very it's you know it's once you've Once you've picked an engineering major in college, it's going to be pretty hard to ever become as good at literature as somebody who's picked an English major. right like you You do cut off your options, and and it's a necessary part of growing up. And samely, you get married, maybe to this person, but not that person. And you just say, OK, that's you know all these other people are no longer options. You move to this city, you put your kids in this school, et cetera. There's a way in which you just have to accept that the whole world actually is not your oyster if you want to really put down roots and know what it's like to live a real human life. And I think that collectively in the West and especially the Anglo-American world, we're being confronted with a

00:53:36

Speaker

big need to read so just to learn that lesson and say like, look, I like the idea of being global. I like the idea of appreciating all these cultures. But frankly, I don't know a damn thing about most of them. You know, I can't really appreciate them. It's maybe I should just learn about my own and then be able to have good boundaries you know so that when I encounter somebody from Sri Lanka or someplace,

00:53:57

Speaker

I will I will not inappropriately assume that she's going to be just like me and have the same attitudes. Right. Because she probably won't. Right. You know, there's a kind of projection that the psychological projection that the globalized attitude makes possible and even encourages. And you see that, you know, with the disasters like the Iraq invasion in the 2000s, where the leaders of our country assumed that inside of every Iraqi was basically a ah little liberal Democrat waiting to just be freed from oppression. And it's like, well,

00:54:25

Speaker

No, like people have different values and different commitments and and you can't just project your own values onto the world. It it leads to disaster. I didn't expect to be accused of being an imperialist on the call, but i it's an interesting it's interesting. It's really interesting. To be fair, I accuse myself of the same thing. Sure, sure, sure. I'm not taking offense. Yeah, I like that. i It's an interesting perspective. I'm going to have to chew on that. There's a lot of geopolitics that I'm kind of interested, like, or pulled into in this conversation, but i I want to make sure that we make time for the conversation about Christianity and

Personal Religious Journey

00:55:03

Speaker

Catholicism. yeah

00:55:04

Speaker

And so I would love to start with just if you're willing to share just something about your conversion and like what led you there, having this background in the sciences and then the humanities and not having a ah background in Christianity. I think maybe you did like as part of your family, but you weren't raised in it. Yeah. I mean, that like most Americans, my grandparents were Christian, but my, you know.

00:55:27

Speaker

But that had not that was not passed down to my parents, really. Yeah. Well, I think you know in it's relevant that we were just talking about this whole globalization thing, because I think that was that's that's an important part of this of that process for me. When I was in grad school, first in grad school, I just wanted to take classes on all the cool religions, you know all the different ones, Taoism, Hinduism,

00:55:53

Speaker

um because I felt an obligation to know about the world, to be informed. you know And then there comes a point where it's like, okay, I know i know a dab a dab of the Puranas and you know the Ramayana, and I know I've read the Daodejing in multiple translations and I can talk about the Laozi, which is the other sort of foundational text of Taoism. The Zhuangzi. Sorry, the Zhuangzi. Yeah, Laozi is the Tao Te Ching. Thank you. Right. But it's like, it just felt like scattering, scattering the seed too broadly. You know, it's like, well, let's, yeah, but like, I don't know anything about the tradition that my grandparents were were born. In a way, like, maybe I should just look at that and and not assume that

00:56:39

Speaker

some a tradition from far away must necessarily be better just because it's from far away. I think the real catalyst for my conversion came when I was in, I actually was in Turkey. I was there for a conference in Istanbul in grad school right as I was writing my dissertation. So I was close to the end of my PhD and with ah another friend who was attending, going to the same conference we from from my PhD program at BU. we We arrived a little early and we we went and explored around Turkey a bit. So we went to Konya, which is a city where Rumi is buried.

00:57:17

Speaker

and that was That was a really a meaningful place for me because the fellowship that my dad was part of, the Sufi fellowship, was very involved in in some of the... The guy who trans who create who wrote the most influential translation of Rumi in america in the English-speaking world now is a member of that fellowship. And so there's ah a strong connection with Sufi. Is that comanba Coleman Barks? Coleman Barks, yeah. And so the you know visiting that shrine, Rumi's mausoleum and shrine, but so as you know that was special in saying there's a little statue or not a statue, a marker on the street corner where he supposedly met Shams. Oh, wow. First time, you know, and and then we went on to Cappadocia, where these vast underground cities and caves were dug out by Christians in the early centuries, maybe for protection, for retreat into the desert.

00:58:06

Speaker

And you can go, there's there's an open-air museum where you can go and you can see the the most beautiful of the beautiful of these chapels and caves that were carved out literally like with chisels, you know, out of the stone in what they call fairy chimneys, which are these basically large, what we call in ah in the West, hoodoos, like large pillars of sandstone that were all that's left out of erosion. erosion So you can go to these chapels and you see this beautiful iconography that's, you know, 1500 years old and you start to get this feeling like, wow, these guys really meant this. They were willing to live out in the desert, carve their homes out of stone, you know, live in this pretty inhospitable environment and write these amazing treatises. This is where so I don't know if you've yet but these guys might be obscure outside the Christian world, but inside their their central St. Basil, the great um Gregory of Nyssa, Gregory, I think Gregory Nazias also.

00:59:02

Speaker

were what they call the Cappadocian Fathers. um there're Some of the most influential theologians, and especially in the Eastern Church, and they all lived here. and You can also just go wandering out into the desert on your own on footpaths, it's such as National Park, and you just you'll you'll be wandering up and you'll see a cave far up in a cliff and you'll climb up to it and you'll find a chapel that somebody carved out more than a thousand years ago with iconography still on the on the walls. you know something Something that you find a lot is wine presses. They carve wine presses into the walls because if you're Christian, you need you need wine, you know? and so That was really cool. And in in the more I saw it, the more, and then and then the more I thought that, gosh, this is this is a pattern that has been repeating itself in time for a lot longer than I've realized. A, and B, this version of Christianity is so much more beautiful than the crap version that we have in in the States where like you can't tell whether a church is, and there's a fun game, drive around Houston and tell and and try to identify ah church, um Ikea, or high school.

01:00:08

Speaker

it's just ah just a big block, a rectangular squat hulking building behind an acre of grass. acres of grass It's like therere there's just an ugliness to to a lot of American Christianity that i I would never have converted to Christianity if that were my only reference point. I had to see something that was more beautiful and deeper. And then we we went back to Istanbul and we you know did our conference and then we stuck around for a couple of days and I visited the Ecumenical Patriarchate um and in Constantinople, which is the and rough, rough equivalent to the Vatican for the Eastern Orthodox Church. Very rough, because it's not, it's not, example but it's that it's the mother church for the Eastern Orthodox world. And they sing great vespers every Saturday night. So you can go and we did that. Yeah, and just like standing in this chapel, hearing and these monks chant for like an hour with candle and gold and shadows and incense and

01:01:03

Speaker

it was like, you know, I was like, I'm a hippie by background and this I can I can I can grok this like I recognize this. This is all this is all the same kind of stuff. It's like incense and candles, you know, but it's somehow feels deeper and and and it's it's there's a there's a willingness to confront the dark that I i think a lot of new age religion doesn't have religion, whatever the new, you know, that that kind of world in America does not have because of essentially, it's consumerist aspects, it's literally dark in the church. um There's a sense of somberness, they're not afraid of somberness, like, like American culture often is. And i I thought to myself, whatever these guys have, I want it, you know, this is this is better than what I have, it's older, it's rooted, it says something meaningful about what humans are. And it calls it calls you to

01:01:54

Speaker

a deeper challenge. You're going to have to change your life, you know, you can't really commit to this way of life and still go out and party, you know, like all the time. I mean, I'm not a teetotaler now, you know, I will have friends over and have a glass of wine or whatever. But like, if you're getting drunk regularly, or really at all, you know, then you're probably not that's that's not super compatible with the Christian life.

01:02:16

Speaker

in a serious Christian life. And I found that that was good because my parents, my mom that stepda mom and dad had been very serious alcoholics and that was the kind of environment I was raised in. So I was already predisposed to drink too much. And you know so there were there were ways in which the call to discipline was needed and and helpful. And so I just sort of started moving more towards Christianity and then eventually got baptized. you know and and then eventually moved into the Catholic Church, which is sort of just like a fulfillment of um the rest of that movement, I think. it's not It's not discontinuous. It's not like, you know, it's not like, I think, Protestants or somehow, like, lesser or whatever. It's just more just a, it's where the path led. Well, if you're if you're reaching for that kind of numinous, like, mystical, i it seems to me from the outside that, yeah, that the Catholic and the Orthodox traditions

01:03:12

Speaker

do that better than the Protestants. even you know And I don't know that's high church Protestantism, which I don't know that well, but definitely, you know aesthetically, Catholicism seems more attractive. So to the degree that like you were moved by an aesthetic experience, which it seems like is in there, it makes sense that you would be drawn in that direction rather than like some Lutheran kind of like like blank walls and just like a simple, yeah. yeah Yeah, I mean, and there's also, you know, to reconnect to my academic journey, um there's a sense of which I'm like, an and I am an anthropologist, I'm not a, I'm not a cultural anthropologist, my my degree is not an anthropology, there are a lot of skills that anthropologists that are trained have that I don't have. But that's the world I was interested in. And one of my dissertation readers was anthropologists, a lot of the

01:04:00

Speaker

the work that I cite in my writings is anthropology. So something interesting there is there was, there's, I don't know of an anthropologist who's ever converted to Protestantism. You know, it's a very secular, it's a very secular discipline, very left wing these days, ah very left wing, but it has always been very secular. And, but there's a couple of examples of major conversions, especially in the mid 20th century, E.E. Evans Pritchard and Victor Turner being two examples, British social anthropologists of the mid century tradition.

01:04:30

Speaker

who, through their experience, found themselves just being drawn to Catholicism. I mean, Victor Turner was an expert in, I think, the Nindemu people in Africa and spent his career really studying the what he called the ritual process. And so it's not just rituals, but the way that ritual kind of cycles between periods of stability and order and transition, right? That was his expertise in this culture and how well this culture orchestrated these transitions.

01:04:58

Speaker

you know, initiation rites, new consecrations for kings, sorry, coronations for kings, things like that, right? Anything where you have a transition. And and i think that he came I think that when he started feeling called to faith, it was like, well, you know Catholicism is like that. It has It has a mastery of the ritual disciplines that that I think all cultures need embedded in its institutional memory, it's its institutional structure. So that there are these transitions, there there that you know you you ritualize events like marriages, like funerals, like first comedians, things like that in a way that that makes them marked and kind of makes it feel like the transition is

01:05:41

Speaker

stable solid So it reduces ambiguity in a way, which is a um very important feature function of ritual in human culture is to is to take essentially analog um data that's that's messy and ambiguous and and snap it into digital. right like It's like youre you know you you move to get married in layers of times where you love each other, is times where you feel like not as great about each other, especially when you're planning a wedding, when it's all frustrating and everything. and like all that so so The actual flow in time of feelings is all wavy and up and down, it's analog and messy, red but like the wedding itself is just, right you're not married, and then you are married it clarifies, so it's a digitization in a way.

01:06:23

Speaker

almost like an action potential in a neuron. That's a fun analogy. Yeah. Well, I get that from Roy Rappaport, another fantastic anthropologist who's very influential on me. And and he he actually describes it that way because just like an action potential,

01:06:37

Speaker

um gates the information transmission downstream from its axon, a wedding gates information downstream socially. Socially, it's not relevant what your kind of fluctuations of how you're feeling about each other are. What's relevant is that legally you're married, right? And so it just reduces the amount of data that other people have to process.

01:06:55

Speaker

And same with the baptism, same with the rite of passage. Exactly. The rites of passage are a great example, especially for boys, because the transition from boy to man is so biologically ambiguous and long and met and it's just like there's no one clear point. You know, at least with girls, it's like you've menstruate and it's culturally a lot of cultures say like, okay, that's the moment, right? But for men, it's like, I don't know, what what is it? you know and then And so you have these rituals that kind of say like, yeah, we're not listening to biology here, we're we're actually imposing a structure on it. right so So I think Catholicism in its in it functional forms, when it's functioning well, has a lot of that kind of wisdom built into it. And and ultimately, you know there's also the part that you wanted to talk about the miracle, where it's just like, I started to just think it was true.

01:07:41

Speaker

you know that is you cant You can't keep doing the rituals forever if you're just doing them for you know stabilizing your life or whatever. you know if you if you If you just got some sort of like function you want to get out of them, it's difficult to keep doing that forever. Eventually, you have to kind of decide, am I in or out? Do I believe this stuff? Or do I think do i think it's a nice fiction? And if you if you really think it's a nice fiction,

01:08:03

Speaker

and maybe you can hang on for, you know, going to church and doing the rituals, but it's not as easy. So so there is a way in which I kind of had this parallel intellectual journey where from like, ah from like a anthropological perspective, I came to see that this is something that is needed, these these structuring, meaning creating, attention shaping, ritual influences on my mind and body right and and my relationships with the social world. But also there's a an intellectual journey and a spiritual journey and an epistemic journey um that led me to kind of think that there's something to it. isn It's not just nice rituals. I want to go there before I do. so There's a couple things you that that kind of distinction like when you're talking about um someone believing it versus just someone doing the rituals because they think it's

01:08:59

Speaker

good idea culturally it's good for their you know it reminds me of the recent I'm sure you came across this ah I and Hershey Ali is that her name to yeah that article where she says we should all be Christians like and she has this like here's why I'm converted to Christianity and this long list of like just kind of completely utilitarian, like, well, this is good for the culture, it's good to combat, you know, i she's kind of very anti-Islam, and so it's good to combat this kind of other way, and like, this completely, like, yeah, but that's not what it means to be a Christian, like, you can't, like, it was, it maddened me to the point, you know, of not being a Christian, but but just feeling like,

01:09:39

Speaker

no that's like but that's not what being a christian means it doesn't mean thinking it's a good idea it means believing something right and actually this was kind of in a way the the the seed of this my what part of one of the inputs to me wanting to have a conversation with someone who is a christian so that's you know that's one data point um and then just to go back it's funny you talked about the doubting like the two You know the doubting is an enormous influence on me. It's like my favorite religious book I mean, I just think it's an extraordinary beautiful piece of writing and true Like and you know and it just transit like it's true like what it says and you know in a way it's kind of it it has like aspects of it that are incredible that that I would describe as post-modern almost right like in the kind of

01:10:27

Speaker

in the in its relationship between language and reality and all the stuff, right? I just think it's it's extraordinary. and you know And it doesn't within it have any kind of claim of miracles, although there are miracles in the tradition. There's a lot of kind of you know magical stuff in in the tradition. And then the other the other kind of huge influence for me is Zen Buddhism, which is very related to Taoism. It's kind of like it's yeah Taoist-flavored Buddhism, right? yeahp Which also, for the most part, Zen Buddhism does not take on the kind of miraculous trappings of other forms of right. days in in In other forms of Buddhism, there's a kind of, you know, it's it's much more traditionally religious and Zen is like very skeptical of all of that and Zen is very practical and it's very kind of like, and that the kind of epistemic

01:11:16

Speaker

stance of Zen is you don't know shit, and you're never going to know shit, just sit down, shut up, and see what happens, right? More or less. And I'm, of course, digesting a very westernized version of Zen. it's not you know I did not grow up in Japan and study in those monasteries. So you know take take all of this with a grain of salt that this is American Zen.

01:11:35

Speaker

what I'll say about like it's a very attractive to me and you know with both of these traditions which I i i love and to greater or lesser degree of practice in of my life but never kind of like I've never taken refuge for example like I'm still you know flailing around in samsara right it's attractive to me and Christianity is attracted to me and preparing for this call I've never read the Bible like I mean I don't think many people have read the Bible cover's cover to cover so I bought I bought a Bible To read preparing for this call i didn't think out you know i wasn't gonna get through it but i thought well let me let me i would i press it yeah i mean yeah let me let me have a crack at it and you know and and so and i and there was a moment like i opened the you know i open it up it's genesis and you know i kind of know that you know i know and i know the first part pretty well and i started reading it it just crossed my mind like.

01:12:21

Speaker

What if I'm just converted like what if I read this book and like my heart is moved and I just go oh this is it right and I have this moment of like, you know, kind of excitement and hope of like, well, wouldn't that be really nice? Wouldn't it be really nice? And then, you know, within, I don't know, a few pages I was like,

01:12:39

Speaker

oh no wait a second this is dumb and and just kind of you know just had my my typical falling out with it which is that i it there there is not that much about it personally that i find beautiful when i compare it with the dao de jing or or even when i compare it with some of the the the the sutras like it it just feels um you know part of what i love about buddhism and General and you know what is in the general and and then is is the kind of the practicality and the the sense it just seems True to me and and you know and then more recently the other one and super kind of rattling off religions But I I recently came across Kashmir Shaivism. This is amazing book. It's called tantra illuminated by an American guy ah Christopher Wallace he called a hoorish

01:13:31

Speaker

And that's ah about Kashmir Shaivism. And I was reading that book and I had this experience of like, oh, wait, this one is true. Like I thought that there was just a piece of truth in all the religious. I read that, had a very powerful response to that. But again, like the claims that these things are making are kind of fundamentally metaphysical claims. Yeah. And that that it's easy to resonate with these metaphysical claims.

01:13:58

Speaker

in a way that, you know i i you know, I wish and it's, you know, the thing about Christianity is to be Christian in America is kind of convenient because like it's ah it's available, right? And it's, it's so it's you know, you're youre you were kind of part of the cultural thing. I mean, talk about belonging. And so this is just me kind of revealing my own like wrestling with this thing that like, wow, it'd be great. Like i I would have been delighted in a way. I mean, it would have been baffling. But if I'd read the, you know, started of reading the Bible and like, you know, had this kind of, you know,

01:14:26

Speaker